Germany’s Nazi regime confiscated or otherwise appropriated over 600,000 works of fine art between 1933 and 1945. Some works were hoarded, some destroyed, and many others sold or traded for profit. What was behind this heinous activity? And how did the perpetrators manage to dispose of so much art that, even now, more than 100,000 looted works are still unaccounted for? Collaborators within Germany and even in Allied countries, including the United States, contributed to help the Nazis process and profit off this well-organized crime.

◊

“In order not to be considered lacking in artistic understanding, people stood for every mockery of art and ended up by becoming really uncertain in the judgment of good and bad.” – Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf

Adolf Hitler felt humiliated by modern art, and he was determined to exact his revenge. Rejected for admission to art school in Vienna as a painter, he rationalized that it was the fault of the era, and not his mediocre skill, that denied him his deserved future as a great artist. As early as his writing of Mein Kampf, he railed against the “degeneracy” of contemporary art as opposed to the older, more traditional art of Northern Europe, which he praised for its Germanic authenticity.

Emil Nolde, Pentecost, 1909. Over 1,000 paintings by Nolde were labelled "sick and degenerate" and seized by the Nazis.

So when Hitler and his Nazi Party ascended to power early in 1933, intervening in the cultural production of art was prime on his agenda, along with enacting his nefarious plan to reshape Germany – and all of Europe – to reflect his grotesquely distorted vision.

The Nazis espoused twisted ideals of nationalistic “purity,” and set about enacting agendas both overt and covert to remove all traces of non-Germanic, and particularly Jewish, influences in their culture. Those plans – the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” (Endlösung der Judenfrage) – included the mass removal of millions of citizens from their homes, dispossessing them of their property, and eventually exterminating 6 million Jews and as many as another 5 million “undesirables” in the Holocaust.

Hitler vs. the Art of His Time

The Nazis’ earliest steps did not reveal their Final Solution. Early in 1933, Hitler and his lieutenants, including Hermann Goering and Joseph Goebbels, began their cultural campaign. Germanic culture had been “despoiled” by influences inimical to the standards of “pure” Germanic heritage, they raved. Cultural artifacts and the fine arts had been infiltrated by foreign influences, and the German people were demanding a return to the unspoiled “innocence” associated with such “Aryan” ideals as health and racial purity.

Once Hitler seized power, he was free to unleash his vengeful fury on the sources of his hurt pride: modern art in all its diverse forms. He detested all art that, as he viewed it, distorted the clear-eyed, “classical” ideals of accurate representation, heroic scenes, and “uplifting” themes. He abhorred modernist art movements such as Expressionism, Surrealism, Dada, and especially Cubism as practiced by so-called “Bolsheviks and Jews” like Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Now, having attained virtually unchecked power, he was in a position to do something about it. And he swiftly did so.

Georges Braque, The Guitar, 1910. Hitler detested Cubism, a style of art originated by Braque along with Pablo Picasso. This painting was shown in the Nazi's "Degenerate Art" Exhibition.

Art “Protection” and the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition

Hitler organized a government-empowered committee called the Kunstschutz, which translates to “art protection,” but whose mission was directed at anything but. The Kunstschutz’s first order of business was to “cleanse” Germany’s museums of all “undesirable” art – meaning non-realistic, abstract art of the times as well as works by Jews. And all of Germany’s museums were compelled to comply. Once this deed was complete, leaving Germany’s public art collections virtually bereft of art made after around 1850, the committee turned its attention to art dealers, seizing their collections and banning dealers with Jewish connections and/or clients from practicing their trade.

Now, what to do with all these confiscated paintings, graphic art, and sculpture? Many works were soon gathered together and put on display in a sordid manner, in an exhibition given the shameful sobriquet “Degenerate Art” (Entartete Kunst). Meant to display the unpatriotic, base urges of the now-excluded class of contemporary artists and their patrons, the exhibition contained literally hundreds of works crammed together, one atop another, in too-small gallery space with anti-art and anti-culture slogans graffitied on the walls.

Adolf Hitler tours the galleries of the "Degenerate Art" Exhibition in Munich, 1937.

It didn’t stop there. Just down the street from the show was another exhibition meant to teach the Germans which art practices and themes were now acceptable and honorable: It was called the “Great German Art Exhibition” (Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung). Hitler liked only a few kinds of representational art, and so this is what was shown: portraits and landscapes, primarily, that promoted the Aryan ideal. Blonde goddesses and Alpine scenes predominated, in a style mimicking that of the European Old Masters.

The Nazis had a three-pronged strategy for plundering art and gathering masterworks for their own purposes: (1) drain Germany of its “degenerate” art; (2) confiscate Jewish-held art from private collections and Jewish institutions, including schools and synagogues, in conquered countries; and (3) levy outrageous taxes against fleeing Jewish families and confiscate their art collections as “payment.”

Germans, for whatever cause, voted with their feet; “Degenerate Art” had a million visitors in its Munich run, and, as it toured the hinterlands, another million came to view it in Berlin, Leipzig, Dusseldorf, and other cities, concluding its run in Vienna and Salzburg.

Not everyone fell for the propaganda, to be sure. Contemporaneous diaries have recently come to light that reveal at least one viewer saw the art for what it was. Berlin resident Franz Göll viewed “The War,” an Otto Dix painting the show’s organizers termed “anti-German.” Göll felt differently, writing, “The picture is not a bloody-minded depiction of the degenerate, war is.” I suspect others looked upon this reprehensible display with sorrow, for the artists and, perhaps, for their own futures.

Otto Dix, The War, 1932. Dix's war paintings were anathema to the Nazis, who considered them "an insult to the German heroes of the Great War."

Sales of Banned Art Funds the Nazi War Machine

Make no mistake, this was a systematic and widespread effort to seize art. And even with the wheels of the German government greased to support it, this “disappearing act” needed help. To their undying disgrace, a group of former contemporary art dealers were pressed into service to assist in acquiring artworks they formerly promoted. Only now, the goal was to get rid of it – and use the profits to fund the Nazi war machine.

Prime among this group was the compliant German art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt. Gurlitt accepted his new assignment with relish, collecting hundreds of modern artworks – 650 alone from the “Degenerate Art” show – and deciding what was to become of them.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler called modern art the “hallucinations of lunatics or criminals” and claimed it represented the “poisoning of the healthy instinct of our people.” For more on this facet of Nazi rule, view Nazi Stolen Art: The Final Restitution on MagellanTV.

Here is where Hitler’s nefarious plan became diabolical. Of course, thousands of works were immediately destroyed, burned in a controlled conflagration masterminded by Gurlitt outside a fire station. But destroying the art wasn’t the ultimate goal; profiting off banned and seized art was.

Hitler had a grand, if insane, vision for the future of art. Once it had been cleansed of its “unhealthy” Jewish influence, artists and craftsmen would be put to work creating the art of the Third Reich. Healthy, inspirational “art of the people” would be displayed alongside the finest art of olden times in his hometown of Linz, which was selected to embody the “new Athens” of Hitler’s twisted mind.

To house his vision of art, Hitler planned a massive structure, the self-aggrandizingly named Führermuseum, with a European Cultural Center surrounding it. To fill it, he and his henchmen plundered not only German art institutions but also the museums of countries to the east and west that came under Nazi control.

The "Degenerate Art" Exhibition had a million viewers in its Munich run, and a million more as it traveled through Germany and Austria.

Gurlitt, along with others, including such self-styled connoisseurs as Goehring and Goebbels, received all this art as it arrived from France, Italy, the Soviet Union and elsewhere, and separated the desirable from the “undesirable” pieces. While the prized selections of classical art were amassed for display in the Führermuseum, the contemporary art was up for grabs. For instance, Goering had his own secret stash of art he favored, including the work of German Expressionists he appreciated.

The Nazis had two separate objectives in the disposition of stolen art, including the proscribed contemporary examples of Futurism, Fauvism, and more: Less desirable pieces were sold for cash, and the most valuable pieces were traded for the classical Old Master paintings Hitler desired for his museum.

For his part, Gurlitt, along with his accomplices in the “art protection” racket, was placed in charge of monetizing the art booty they were collecting. Through a set of auctions and private deals, Gurlitt sold this banned art to collectors and collections around the world. In particular, he was tasked with selling to non-German collectors and receiving foreign currency (preferred over Nazi Reichsmarks), which, with a cut reserved for the dealers, went to the Nazi war machine.

Liberation, or Greed? Profiting from Plundered Art

Incredibly, collectors outside occupied Europe, even in the United States, collaborated with Nazi art dealers in receiving these stolen goods, even to the point of offering surreptitious financial support to the Third Reich and its dreams of world domination.

In America, Joseph Pulitzer, Jr., purchased some of this art. So did New York’s Museum of Modern Art, though its director Alfred Barr used intermediaries to hide the source of these paintings and sculpture.

Paul Klee, Senecio, 1922. Klee and his work were condemned by the Nazis. Three of his watercolors were included in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition.

To be fair, some of these brokers and collectors may have thought they were “liberating” priceless art from dastardly hands; and in fact, they were. Yet they richly profited (or saw their holdings increase in value) from these below-market purchases, and often resisted humanitarian calls for the art to be repatriated to their countries of origin and their original owners, or their heirs.

These artworks, many said to have been sold for “ten cents a kilo,” numbered in the hundreds of thousands. It’s estimated that the Nazis seized as many as 600,000 works of art – up to 20 percent of all art that existed in Europe at that time – from both public collections and private hands. And up to 100,000 pieces are to this day still unaccounted for.

Hildebrand Gurlitt held a secret that may account for his quisling-like behavior on behalf of the Nazi cause. His paternal grandmother was Jewish, making him potentially an undesirable to the Nazis. However, he did his best to serve Hitler, concealing his heritage and “just following orders.”

According to BBC News, Gurlitt himself hoarded thousands of works that were stashed behind a wall for more than 50 years, until his son Cornelius was caught trying to sell one of the family’s hidden masterpieces in 2012. Russia now has an estimated 120,000 objects collected in WWII, including art, books, rare manuscripts and more, in and around Moscow. And Austria is believed to have approximately 10,000 works hidden in monasteries.

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow Red Blue, 1925. Russian-born Kandinsky was condemned by the Nazis as a "Bolshevik"; 57 of his works were confiscated and later destroyed.

Returning Art to Its Owners: A Harder Task than It Appears

If you saw the 2014 film The Monuments Men, you know that the U.S. military, under the guidance of the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner to the CIA), made a good-faith effort, beginning in the final years of the war, to protect and preserve the cultural treasures that had been plundered by the Nazi regime. However, there was a flaw in the orders under which they operated: Rather than being charged with returning artworks to their rightful owners (most likely an impossible task at the time), they instead delivered all the art they found to the governments of the countries where the works originated.

In some cases, this meant returning the artworks to the powers that had stolen them in the first place. And so, many artworks were not returned to individual owners. This is a problem that persists even today in a number of countries, including Russia, Hungary, and Poland, as well as, somewhat surprisingly, Italy and Spain.

A key sticking point keeping art from being returned is the question of ascertaining provenance, that is, the chain of possession of each work. In the chaos of Nazi looting, provenance became especially murky, and records, which even the Nazis kept to some degree, have been destroyed or lost in the “fog” of war.

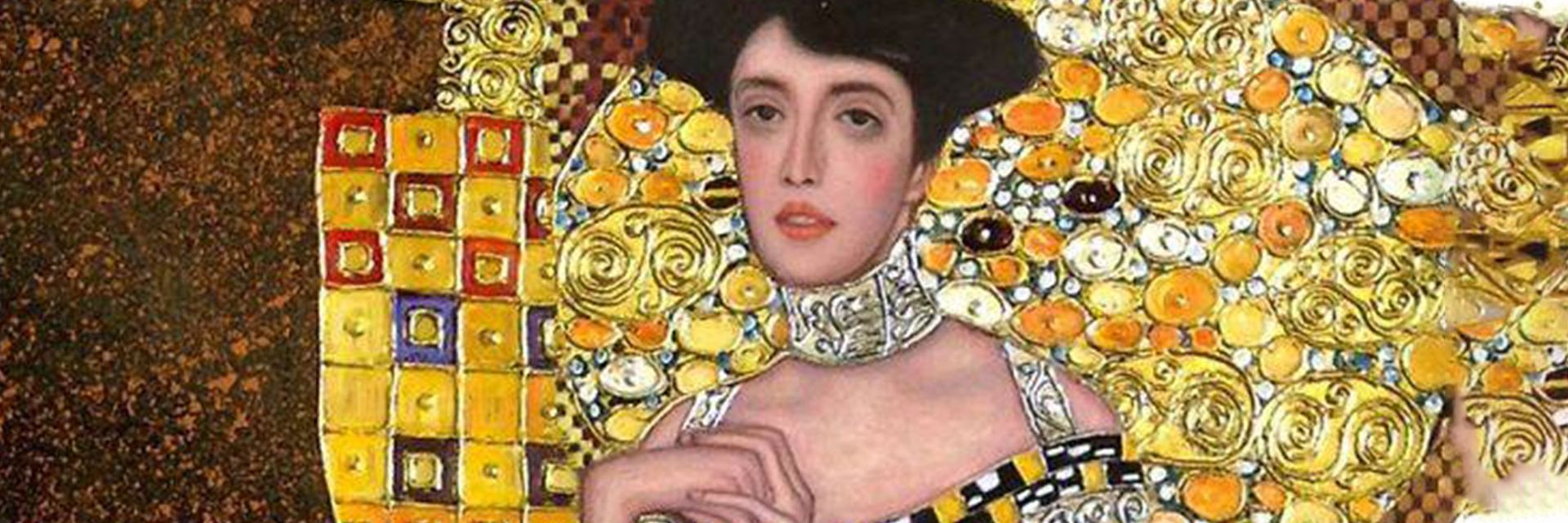

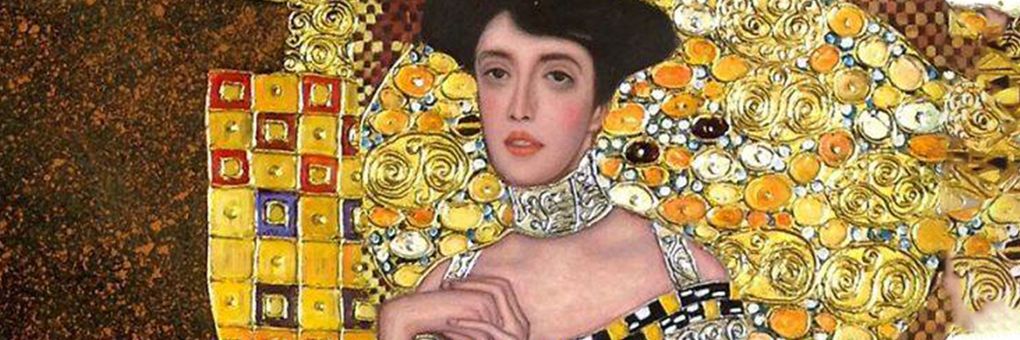

Klimt’s Masterpiece and Its Troubled Provenance

The result of the confusion (or obfuscation) has made for some celebrated cases of artworks held by museums or in private hands being sought by their original owners through difficult and contested lawsuits. For example, the sumptuous and luminous painting Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, completed by Gustav Klimt in 1907, was confiscated from its Jewish owners in Vienna by Nazi authorities in 1939. Its owner at the time, a Bloch-Bauer heir, presumed it had been lost forever. But instead, its title had been changed by Nazi dealers.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, 1907. This work was seized by the Nazis in 1939 and held for 68 years.

The masterpiece ended up at Vienna’s state-owned Galerie Belvedere for 68 years until, after dogged litigation – one individual against the Republic of Austria – it was finally returned to Bloch-Bauer heir Maria Altmann in 2006. Altmann chose to sell the painting to Ronald Lauder, art collector and owner of the Neue Galerie in New York City, where it is currently on display.

What Is to be Done About Still-Missing and Unreturned Art?

Unfortunately, the Klimt painting is not an isolated case. Families have fought for years, often unsuccessfully, to have their prized artworks returned, and even now discoveries of hidden or misappropriated art treasure make news.

Some progress has been made, however. More and more art dealers – notably including the world’s two largest auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s – refuse to deal in suspected Nazi-looted art, and a consortium of nations and art professionals have signed on to the 11-point Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, first proposed in 1998 and recommitted to in 2008.

But in many cases, including Cornelius Gurlitt’s mold-covered hidden hoard and the 5,000 works burned to ashes by his father, art – and culture – has been irretrievably harmed. And that is one of the costs of war, beyond the senseless loss of life, that we must guard against, in perpetuity.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, 1907 (detail)