DNA is arguably a human being’s fundamental identity. Consequently, there are lots of questions about when and how it is misused.

◊

A fossilized mosquito encased in amber could contain dinosaur blood. If we can extract the DNA, we could revive an extinct species! We could . . . build a dinosaur theme park – a Jurassic park! (I mean, what else would we do with dino DNA, right?!)

A story like this isn’t just the speculative fiction of a blockbuster movie. Just ask Henrietta Lacks, the woman whose DNA was extracted from a tumor biopsy without her consent. Wait, how did we get from dinosaurs to one of the most infamous cases of medical research conducted without informed consent? The thread is the famous double helix of DNA.

Have you heard about CRISPR? Check out this revealing MagellanTV documentary to find out how this revolutionary DNA-editing technology might be used -- for better and for worse.

What makes me, me – and not someone else? What makes me, me – and not a bird or a worm or some other living thing? Arguably, DNA. The genetic material that makes me human and not another type of organism, and the genomic variation that makes me, me – and not someone else – is my DNA. So, genetically, my identity is human, and within that classification, no other human can be me.

Given the level of individuation DNA provides, combined with theories of personal identity that underpin moral concepts like autonomy, rights, and informed consent, we should think carefully about the possible and actual misuses of DNA. After all, as the wags say, what could possibly go wrong?

The Dead Are Gone but Not Forgotten

Archaeologists, anthropologists, paleoanthropologists, forensic pathologists, and other scientists study the dead. Ancient DNA has much to teach us about ourselves, our history, our present, and our future. So does DNA taken from the recently deceased. Uses include learning the cause of a suspicious death, understanding genetic risk factors for family members, and the progression of disease.

Across disciplines, the scientific enterprise is focused on knowledge. Scientists seek to expand and refine the collective body of knowledge we call “science.” How scientists do their work is facilitated by sensitive instruments and guided by often complex methodologies developed for particular specializations. In very general terms, the scientific method consists of observations that lead to hypotheses that explain the observations, and the development and implementation of experiments to test the hypotheses.

In the realm of postmortem genetic testing, for example, researchers use established techniques for extracting and examining DNA from individuals who died from known diseases. The genetic mutations responsible for diseases like sickle cell anemia and cancer may yield valuable insight that can help people within similar DNA profiles.

Do the Dead Have Rights?

Let’s consider two classes of deceased humans: ancient and recent. To get started, think about how signing a consent form for a medical procedure is commonplace in most countries. You and I have legal protections all the way down to our DNA.

The Long-Since Dead

Ancient dead humans don’t have the same protections. Indeed, there is little regulation of research on ancient DNA, the analysis of which involves the destruction of tissue. There are also few ethical guidelines universally agreed-upon by researchers.

Scientists are increasingly thinking about widening the scope of research considerations. More specifically, many researchers today advocate paying more attention to the context in which empirical facts are established.

For instance, suppose a scientist wants to study the DNA of ancient people in Country X. Suppose further that some of the current inhabitants of Country X claim to be descendants of the ancient peoples. Rather than just “parachuting in” to gather samples and data, shouldn’t the scientist should include sharing research results with interested parties as an element of their process?

The Lancet journal defines a parachute researcher as someone who “drops into a country, makes use of the local infrastructure, personnel, and patients, and then goes home and writes an academic paper for a prestigious journal.” The kicker is that the researcher in question doesn’t even acknowledge the local contributors.

Now suppose a scientist exhumes the remains of your oldest known relative. Tissue samples are taken and DNA analysis conducted. Suppose further that the scientist never asked for any relative’s permission to do all of this, and you never learn what came of the research. You’d likely feel at least vaguely violated, even if you weren’t sure why.

Already, genomic research has yielded important information about connections between ancient peoples and those of us living today. For example, ancient DNA has contributed to disproving claims that there are so-called racially pure populations. It has also served to support Australian Aboriginal claims about ancestry that bolster legal attempts to rectify injustices, such as museums’ claims to own ancient remains. The Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., is one of many museums around the world that have collections of human remains and is grappling with related thorny ethical issues.

A skull at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum (Credit: Wikipedia)

Arguably, the main ethical consideration in working with the ancient dead is minimizing harm to stakeholders. This includes doing the work to identify the stakeholders, obtaining their consent, being mindful of the potential harms to them, minimizing damage to the remains, sharing research results with the affected community, and protecting their privacy.

The Recently Departed

There are similar ethical considerations for the recent dead, but also potentially more ethical minefields. Suppose, for example, a person has steadfastly refused genetic testing despite persistent requests from immediate family members. Suppose further that, after that person dies, their immediate relatives want diagnostic genetic testing performed on the body to determine any genetic risks. This request is in direct opposition to the deceased’s wishes. Does the physician have an ethical obligation only to the deceased?

Now suppose a homicide detective wants DNA results on a murder victim, even though the deceased never gave consent. The results may contribute to solving the case. Should the DNA tests be run?

In both cases, one question is whether or not the dead retain at least some of the rights enjoyed by the living. A related question is whether or not the living have a right to the dead – a right not codified by something like a will or trust, which itemizes the distribution of assets and, in some cases, possession of the decedent’s remains. Still another question is about the intentions of those who seek the DNA.

To learn more about eugenics, watch MagellanTV’s Eugenics: Science's Greatest Scandal

Whether the sample comes from the living or the dead, some motivations for procuring DNA are morally dubious or outright repugnant. Eugenics, for instance, is defined by the National Human Genome Research Institute as “the scientifically inaccurate theory that humans can be improved through selective breeding of populations.” Even when the intentions are arguably noble, as in the pursuit of curing disease, DNA can be unethically extracted and used.

Henrietta Lacks and a Lack of Respect

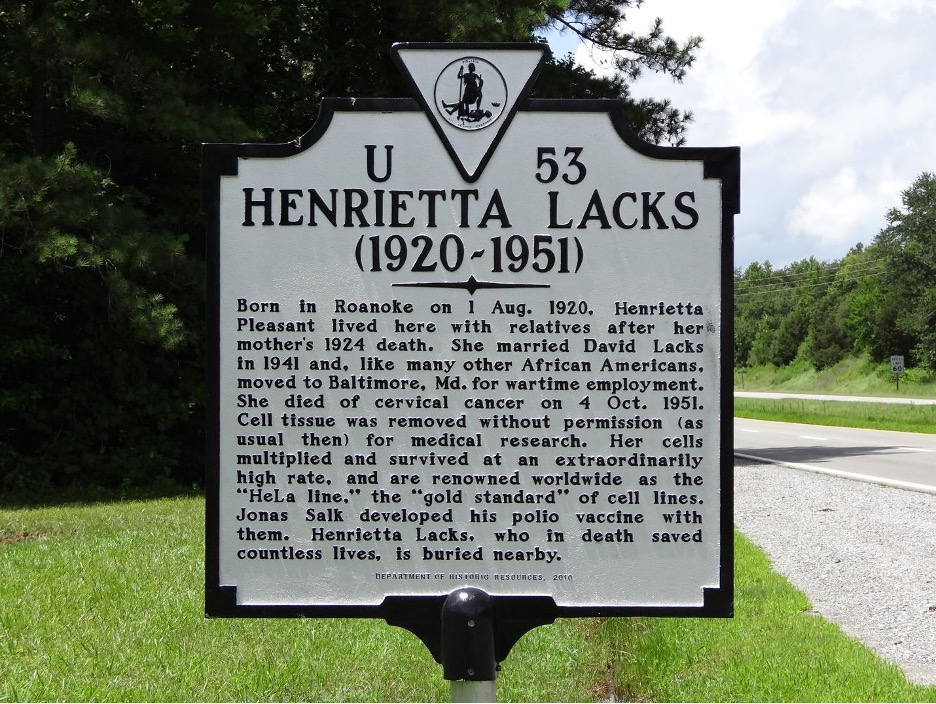

Henrietta Lacks was a mere 31 years old when she died of cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951. Lacks first went to Johns Hopkins, where she was diagnosed with and began treatment for stage 1 cervical cancer, in January of that year. The diagnosis came from tissue samples taken without seeking Lacks’s consent. After her death, and unbeknownst to her husband, her DNA from one of those samples was used for research.

Historical Marker in Clover, VA, Henrietta Lacks’s Birthplace (Credit: Wikipedia)

There are several features that make Lacks’s case significant. First, the cells were deemed “immortal.” Lacks’s cells were the first such capable of reproducing indefinitely in a lab setting. In fact, to date, the cells are still alive and used in lab settings.

“HeLa” was the code name given to Henrietta Lacks’s cells. The first two letters of a patient’s first and last names were used both to identify the source of the cells and to protect the patient’s identity.

In other words, Lacks’s cells replicated, doubling the number at least every day. Cells from other patients died. Consequently, the research opportunities were extraordinary. In the spirit of scientific progress, “Johns Hopkins offered HeLa cells freely and widely for scientific research.” Regardless of their intentions, scientific researchers at the time effectively stole Lacks’s biological identity.

Consent and Autonomy

Second, there were no informed consent practices in the U.S. healthcare system at the time. Women were already effectively shut out of any meaningful consultation about their healthcare in an intensely patriarchal system.

Seeking consent just wasn’t a consideration, despite the fact that, for example, in 1914 a woman named Mary Schloendorff had successfully sued the Society of New York Hospital after doctors ignored Schloendorff’s expressed wish not to undergo surgery and performed a hysterectomy.

Of course, women didn’t even have the right to vote in the United States in 1914, so although Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital established the legal principle of patient autonomy, whereby one has the right to decide what happens to their body, most informal social practices and other legal precedents generally did not recognize women as autonomous beings.

Consider, for example, the fact that, in the United States, a married woman’s identity was legally subsumed under her husband’s. Even after 1875’s Minor v Happersett declared women to be persons, the “fairer sex” was still not person enough to have the right to vote.

It was also partly because the legal principle for informed consent had yet to be established. That didn’t come about in the U.S. until 1957’s Salgo v Leland Stanford Jr University Board of Trustees. The two legal principles join together in a way that feels like they are causally related: My autonomy means you can’t interfere with me without my consent.

Science is a Human Endeavor

Third, Lacks was Black. Jim Crow laws, along with informal socio-economic racism meant that Lacks was a de facto second-class citizen. This despite the fact that Johns Hopkins himself stipulated in his will that the university and hospital he founded would serve Black students and patients – and in fact, it was one of very few top institutions to do so. In this regard, the institution was progressive.

Johns Hopkins (Credit: Wikipedia)

But science is a human endeavor, and as such its practices and conclusions are continually open to revision. When we think about the fact that patients were exploited by medical researchers, we do so with the understanding that such practices were unjust and with the expectation that our autonomy will now be respected.

In at least the first half of the 20th century, however, it was routine practice at Johns Hopkins, for example, to retrieve tissue samples from all cervical cancer patients without their consent, regardless of skin color or even socio-economic status. The fact that Henrietta Lacks was Black, however, makes the practice particularly offensive. Coupled with what happened after, the violation is compounded.

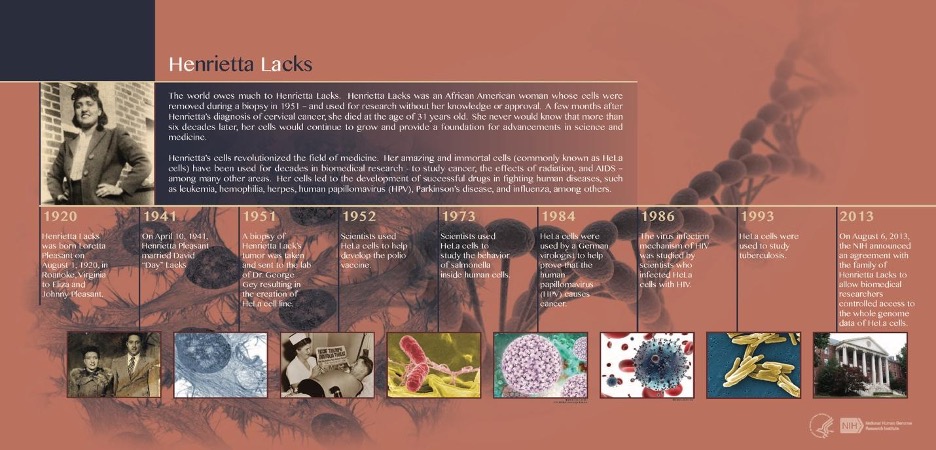

Henrietta Lacks (HeLa) Timeline (Credit: National Human Genome Research Institute)

Not only were Lacks’s cells the only ones that replicated, they have continued to do so for almost 75 years. Henrietta Lacks’s contributions to medical science are astonishing. She was instrumental in the development of the polio vaccine, the HPV vaccine that protects against cervical cancer, and a host of significant advancements in our knowledge of virology, cellular aging, and the human genome.

In 2023, Henrietta Lacks’s family settled a lawsuit with a biotech company alleged to have profited unfairly from HeLa cells. The Lacks family never saw a penny, but arguably more morally problematic was the fact that she and countless other women were never allowed to choose whether or not to participate in medical research.

We cannot disconnect the pursuit of knowledge from the way that pursuit occurs and the ways we use the results. Should we genetically engineer babies? Can DNA databases be secured against breaches? These and other questions are, like most moral problems, not likely to be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. But we should think long and hard about the potential misuses of what is our most fundamental identity.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. Among her relevant publications are essays in Mr. Robot and Philosophy: Beyond Good and Evil Corp (Open Court, 2017), Westworld and Philosophy: Mind Equals Blown (Open Court, 2018), Dave Chappelle and Philosophy: When Keeping it Wrong Gets Real (Open Court, 2021), and Indiana Jones and Philosophy: Why Did It Have to be Socrates? (Wiley-Blackwell, 2023).

Title Image source: Pixabay