There is no longer this separation between ourselves and what is not ourselves. Between the exterior, between me and the others. There’s one absolutely remarkable biological continuity.

—Pierre Henri Gouyon, in The Gut: Our Second Brain

◊

Ask a child where their feelings come from, and they might put their hand over their heart. Ask an adult the same, and they might tell you that feelings ultimately come from the mind. But if you ask a neuroscientist, you might get a more complex answer. While the brain is still considered the seat of consciousness, a growing group of scientists are arguing that the gut’s role in conscious experience should not be ignored, even dubbing it the “second brain.” So, there just might be something to that “gut feeling” many of us have experienced.

Ever since Descartes introduced mind-body dualism, Western science has been preoccupied with the idea that the brain and mind are mostly separate from the body. In recent decades, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) has provided support for this theory: As a barrier penetrable only by the smallest, lipid-soluble molecules, it was thought to prevent most forms of interaction between the brain and the body, other than nerve signaling (more on this later).

In the last 15 years or so, that theory has begun to break down. In fact, scientists have uncovered the gut’s significant influence on the brain and mood, naming this close connection the “gut-brain axis.”

For a fascinating look at the gut-brain connection, watch The Gut: Our Second Brain on MagellanTV.

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Complex Relationship

The gut-brain axis is what scientists refer to as a bidirectional relationship – the brain can “talk” to the gut, but the gut can also “talk” to the brain. In the past, scientists have been more familiar with one direction in this axis than the other: It’s well known, intuitive even, that stress and other troubling emotions can “make your stomach turn.” This happens particularly through the secretion of hormones, especially the stress hormone cortisol, which can alter gut function quite immediately by slowing down digestion, restricting blood and oxygen flow to the gut, and more.

Chronic stress, and chronically high cortisol levels, can also do lasting damage to the gut, resulting in “increased intestinal permeability, impaired absorption of micronutrients, abdominal pain or discomfort, and local and systemic inflammation.” Likewise, decreased stress can benefit gut function, as normal cortisol levels allow blood and oxygen to flow properly to the gut, and, over the long term, allow inflammation to remain in check. It’s even been found that regular mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, and facilitated discussions can aid in weight loss.

But what about the other half of this axis? We know that stress can cause a knot in the stomach, but how is it possible that the gut can influence the brain, especially given the blockade the BBB supposedly imposes?

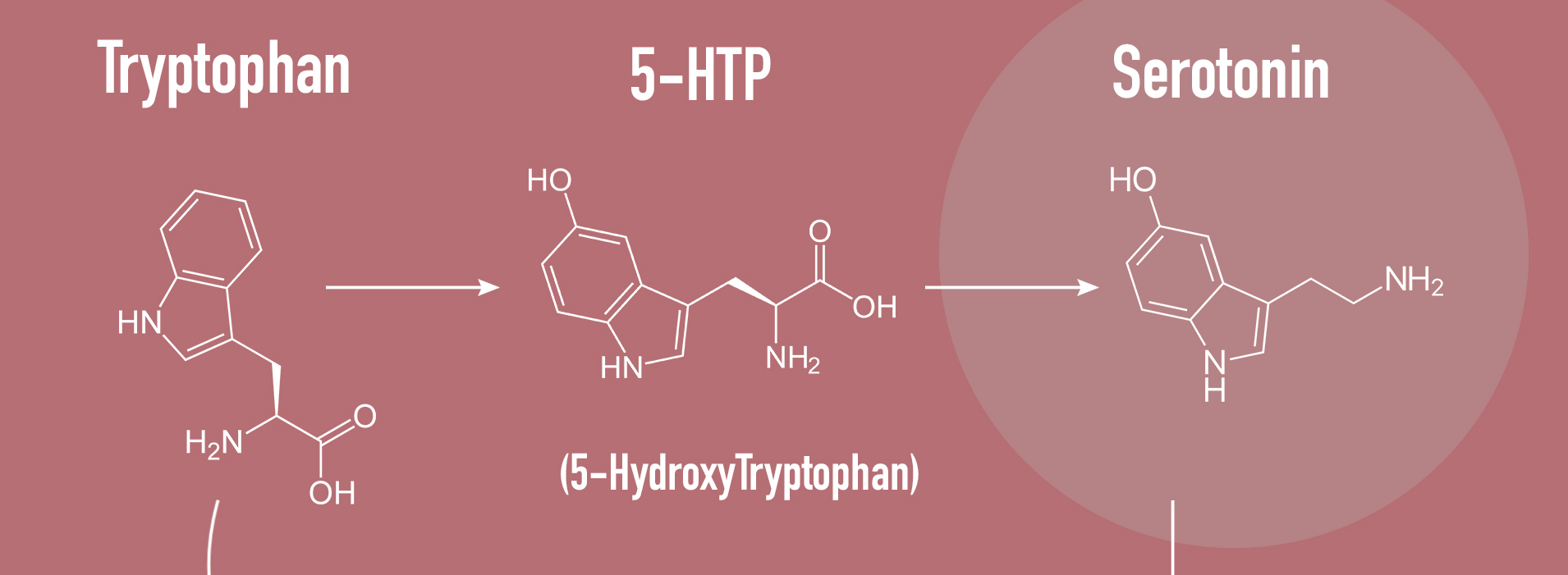

The “production line” through which tryptophan is transformed into serotonin (Credit: bettrocker.com, via Wikimedia Commons)

One Axis, Many Pathways

While the BBB does prevent much mingling between the brain and body, there are exceptions to this rule. Over centuries of evolution, the gut and brain have developed several pathways of communication.

Precursor Production

As we’ve seen, the BBB is a powerful line of defense against poisons and other potentially neurotoxic compounds, but it is not impenetrable. It must selectively allow certain compounds to pass through – otherwise, the brain would have no access to the “building blocks” of important signaling chemicals, and it would not be able to clear waste products.

In general, small, polar, lipid-soluble molecules are more able to cross the barrier, utilizing special carrier proteins embedded into the barrier to aid in the crossing. This is part of what makes alcohol so potent, and also so dangerous: Ethanol, the active molecule, meets all of these qualifications, and therefore can easily cross the BBB into the brain.

Besides alcohol, the BBB also selectively allows other compounds and nutrients to pass through. Tryptophan is one such compound. It perfectly exemplifies the intimate connection between the gut and the brain: The brain requires it to produce mood-boosting serotonin, but tryptophan cannot be produced by the human body, nor do we ingest enough of it to produce the amount of serotonin we need. So where does it come from?

One of the special capabilities of the bacteria that inhabit the human gut microbiome is the ability to synthesize the building blocks of vital messaging molecules – called neurotransmitters – that our nerve cells use to communicate. For example, serotonin, a neurotransmitter that is involved in the pathogenesis of depression and anxiety disorders, is mostly produced by bacteria in the gut.

Ninety-five percent of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, by bacteria as well as by enterochromaffin cells that utilize bacteria-produced “building blocks” such as tryptamine and tryptophan to make the neurotransmitter.

These bacteria act in symbiosis with us: The gut provides a rich nutritional environment, allowing them to thrive, and, in turn, they produce the very neurotransmitters we need to feel well. While the serotonin produced in the gut cannot cross the BBB, those “building blocks” (tryptophan and tryptamine) produced by gut bacteria can. The gut and the brain, then, can communicate via this pathway: gut bacteria produce the building blocks of vital neurotransmitters, which are taken up into the brain and assembled, thus influencing our mood.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

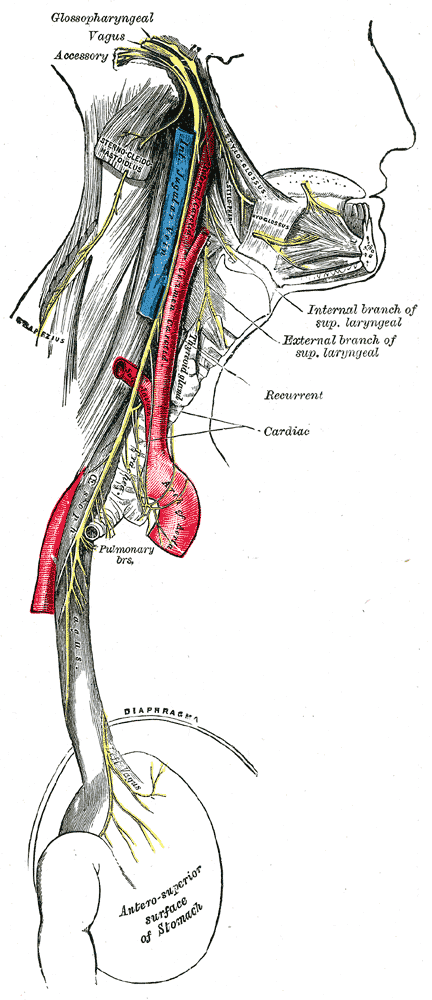

The gut and the brain can communicate in other ways, too. In fact, the longest nerve in the human body runs directly from the brain to the gut. On one end, it connects to the brainstem, and on the other, to the enteric nervous system, a web of nerves that run through the gut, allowing it to perform a variety of functions central to digestion.

This long nerve is called the vagus nerve, and it’s involved in regulating mood, immune response, digestion, and more. It is bidirectional, but, interestingly, 90 percent of its nerve fibers run from the gut to the brain, and only 10 percent run from the brain to the gut. So what kind of information might the gut need to send to the brain?

The vagus nerve runs from the brainstem all the way down to the enteric nervous system. (Credit: Henry Vandyke Parker, via Wikimedia Commons)

There are some obvious answers: information about hunger and fullness, and discomfort or pain. But things get interesting when we investigate further. It is possible that the bacteria lining the gut might play a role in directly stimulating the vagus nerve. This is especially pertinent given that vagus nerve stimulation is now an FDA-verified treatment for depression, and is currently being investigated for use in the treatment of bipolar disorder, inflammatory bowel disease, Alzheimer’s, and more.

Might the vagus nerve, then, represent a direct line of communication between gut bacteria and the brain, allowing them to influence our mood and our likelihood of developing certain mood disorders?

This idea once seemed far-fetched, but the findings of a 2022 study may bear it out. As the authors put it, “Given the high levels of serotonin in the gut, we considered if gut-brain signaling, and specifically the vagal pathway, might contribute to the therapeutic effect of oral selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)” – a front-line treatment for depression and other mood disorders. In other words: Could stimulation of the vagus nerve by bacteria in the gut be behind the mood-boosting effects of SSRIs?

The study lays out several fascinating findings:

- SSRIs only relieve depression when the vagus nerve is intact;

- This SSRI-elicited vagus nerve signaling is only possible with an intact gut epithelium (the home of the gut microbiome!);

- SSRIs seem to induce a shift in microbial diversity.

Taken together, these findings suggest that SSRIs might ultimately derive their mood-altering – and, for many, life-changing – effects from the way they alter microbial diversity and thus vagus nerve activation.

Of course, there is more work to be done to confirm this connection, but, for now, we can say that the vagus nerve plays a vital role in connecting the gut and the brain, which once were thought to be inextricably separate.

Immune Interaction

There’s one last line of communication between the gut and brain to consider, and that’s the immune system. The gut is able to affect the immune system in a variety of ways, which can have dramatic effects on overall health, including mental health.

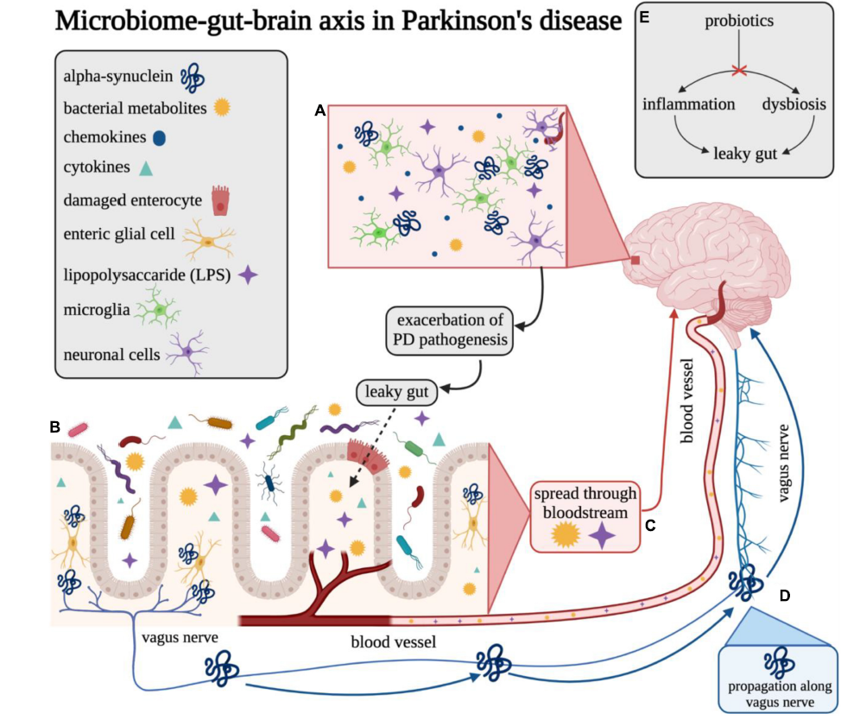

The immune system is one of the most complex systems in the human body. So, of course, its interaction with the gut is similarly bewildering, and not yet fully understood by scientists. One thing medical researchers do know, however, is that when the gut microbiome goes wrong – when it shifts into an unhealthy bacterial state known as dysbiosis – it can cause breakdown of the gut lining. This allows bacteria to pass through the lining, which raises immunological alarm bells, pushing the body into a state of chronic inflammation.

The gut and the brain communicate via immune signaling molecules. Dysbiosis and leaky gut can cause inflammation and release of endotoxins into the bloodstream, which can ultimately exacerbate Parkinson’s pathogenesis as well as other brain disorders. (Image Credit: Emily M. Klann, et al, via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to the negative effects of dysbiosis on the integrity of the gut lining, large-scale bacterial death can also result in inflammation. Dysbiosis can be a trigger for this death, as bacterial diversity decreases and certain bacteria gain “monopolies” in the delicate gut ecosystem. Dying bacteria then release endotoxins, which can move out of the gut and into the bloodstream, triggering the immune system to incite further inflammation. This inflammatory condition has a name: endotoxemia.

Dysbiosis is thus able to incite an inflammatory state in multiple ways. This state of inflammation can have marked negative effects on our mental health. In fact, it has even been suggested that in some cases, depression itself could stem from chronic inflammation.

One recent study looked specifically at the relationship of interferon-alpha, an inflammatory molecule believed to be modulated by gut microbiota, with depressive symptoms. It found that study participants who received interferon-alpha had blunted responses in the ventral striatum, a brain region associated with reward. The reward circuit is made up of multiple interacting brain regions, and it’s also been found that inflammation seems to have the ability to reduce the functional connection between two of these regions: the ventral striatum and the prefrontal cortex.

And on top of all that, inflammation also seems to incite a decrease in the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter central to reward processing. So, not only does inflammation momentarily create decreases in neurotransmitters related to good mood and reward, it also breaks down important mood-related signaling networks, implicating it in creating longer-term effects as well.

Most E. coli are not harmful to humans, and some are even beneficial. (Image Credit: Centers for Disease Control, via Unsplash)

Zeroing In: Are There Specific Microbes Involved in Mood?

The role of gut health in depression has been particularly well-studied in recent years. In one influential 2016 study, it was found that a fecal transplant –basically, a transfer of gut microbiota from one mouse to another – from a “depressive” mouse could allow depressive symptoms to be induced in a non-depressed mouse.

Another study of over a thousand human subjects took this idea further, investigating whether an association could be made between the presence of certain gut bacteria and the presence of depression. The findings? The study, published in Nature, identified 13 microbial taxa (groups of distinct organisms) that seem to be associated with depressive symptoms. The authors note that many of the taxa are involved in the production of the neurotransmitters glutamate, serotonin, and GABA – all of which are “key neurotransmitters for depression.”

Diet and Its Impact on Gut Health

If the composition of our gut bacteria can so dramatically affect our mental health, it stands to reason that we might be able to leverage our diets – the fuel for our gut bacteria – to optimize our mood. This is a theory tested by a raft of recent studies. Because it’s often helpful to understand mood through the lens of how it can go wrong, many of these studies have investigated the connection between diet and depression – whether a healthy diet can play a role in relieving it, and whether an unhealthy diet can induce it.

If we refer back to the several lines of communication between the gut and the brain – precursor production, vagal nerve stimulation, and immune interaction – precursor production and immune interaction both seem likely to be affected by diet.

Indeed, much research on the effect of diet on the gut microbiome and mood has focused on the various anti-inflammatory compounds created by gut microbes when “fed” certain foods. Of course, there are certain microbial taxa that have been found to be top producers of these compounds, and gut microbiomes rich in these taxa would therefore be more likely to have an anti-inflammatory influence.

So what are these taxa, and how can we increase them?

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Eubacterium rectal, Eubacterium hallii, and Ruminococcus bromii are all microbial taxa that have been found to reduce endotoxemia. And the dietary factors thought to increase their abundance? Oligosacharides, which are a kind of fiber found in scallions, white onions, leeks, garlic, kale red cabbage, green cabbage, and broccoli, as well as nectarines, watermelon, pears, blueberries, sour cherries, red currants, raspberries, cantaloupes, figs, and bananas, peas, lentils, yogurt, and cheese.

(Credit: Jose Conejo Saenz, via Pixabay)

Polyphenols, too, foster the growth of these healthy bacteria, and are found in abundance in bright-colored fruits like blueberries, plums, cherries, elderberries, apples, strawberries, black currants, red grapes (this means red wine is rich in polyphenols, too!), black tea, coffee, hazelnuts, spinach, garlic, beans, pecans, and many spices such as cumin, chili peppers, and cloves.

One diet known to be particularly rich in many of these foods is the Mediterranean diet. It has been found by several large studies to alleviate symptoms of depression, and is often suggested as a nutritional way to heal the gut. Of course, longer-term studies are still needed and a Mediterranean diet shouldn’t be used as a stand-alone treatment for severe depression (seek the help of a therapist and psychiatrist for that!), but it does provide a fascinating new strategy for the health-conscious person to remedy moodiness and boost gut health.

So the next time you’re feeling down? Wrap some cantaloupe in prosciutto, slice some pecorino and figs, and pour yourself a glass of red wine. It just might help you feel better!

Ω

Sari Wagner is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. Originally from Philadelphia, she is a graduate of Kenyon College with a degree in neuroscience and studio art. She is passionate about sharing fascinating scientific findings, and allowing everyone to reap the benefits of research.

Title Image created with Dall-E by Sari Wagner.