On D-Day, Canadian troops met little resistance landing on Juno Beach, but their advance ground to a halt around Caen.

◊

Though the phrase “the sun never sets on the British Empire” was most often used to describe the worldwide territory controlled by the United Kingdom in the 19th century, a large number of countries around the globe were still loyal to the British crown at the time World War II began. The largest in territory and one of the most prominent was the Dominion of Canada.

Like other countries in the former empire, Canada was not anxious to repeat the sacrifices its citizens made in World War I when the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. This feeling was particularly strong in French-speaking Quebec. As the war escalated, however, feelings changed. Still, Prime Minister Mackenzie King could not convince parliament to authorize conscription for overseas campaigns.

The First Canadian Army began sending soldiers to England and Hong Kong in 1941. By the Christmas Day surrender of Hong Kong after Japan’s lightning attack, 40 percent of the nearly 2,000 Canadians dispatched to the British possession were killed, wounded, or died soon afterwards in brutal Japanese POW camps.

A combined British-American-Canadian landing in August 1942 at Dieppe, on the northeast coast of France, was a disaster when strong German resistance caused the large-scale raiding force to make a premature withdrawal. Most of the casualties were Canadian infantrymen.

In contrast, the well planned cross-Channel attack, which became Operation Overlord, was the greatest amphibious landing in history. Canada supplied its all-volunteer force to serve in the Second (British) Army, which landed on D-Day east of the First (American) Army.

June 6, 1944: D-Day

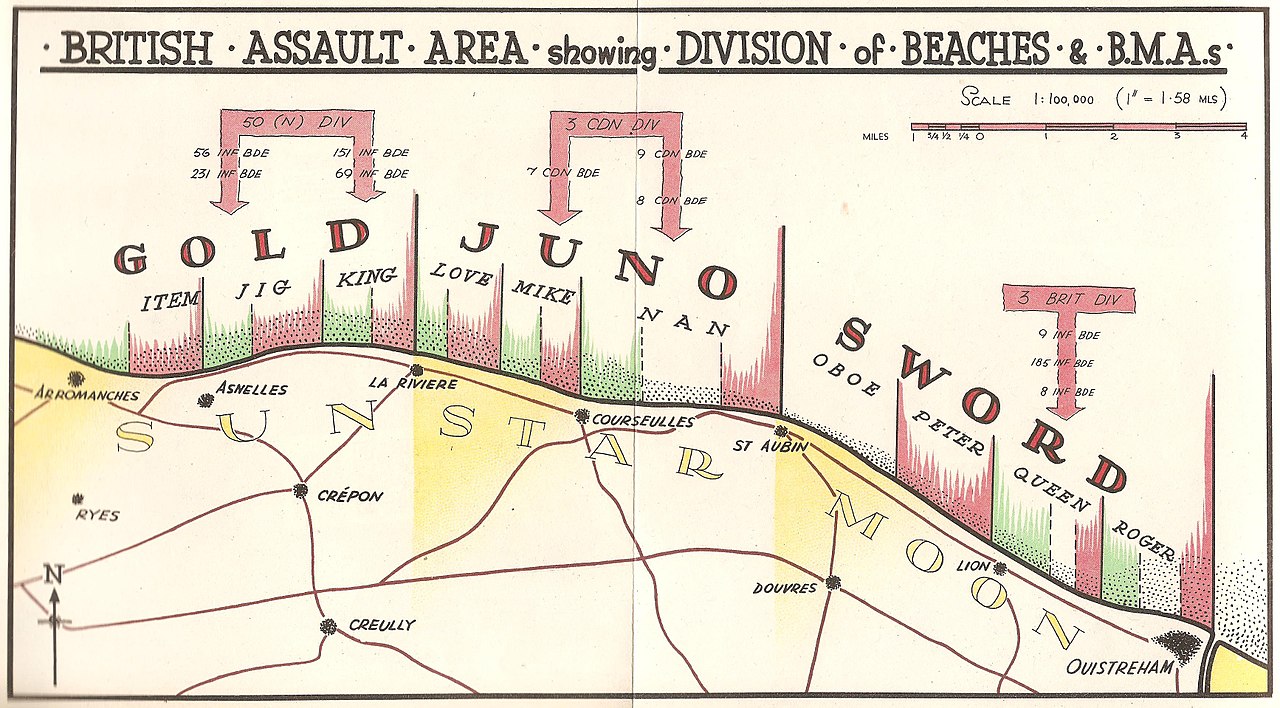

The landings of Operation Overlord were spread across five beaches on the coast of Normandy. The American sector included Utah Beach (facing east) on the Cotentin Peninsula and Omaha Beach (facing north) on the Calvados coast. The beaches in the British/Commonwealth sector were wider and more level than Omaha Beach, just a few kilometers to the west. These beaches, west to east, code named Gold, Juno, and Sword, were separated by reefs that required careful consideration of the tides. After two hours of naval warships shelling German coastal batteries, the landing commenced at precisely 7:25 a.m., one hour after the American landings, due to the tide shifts. All first wave units in the Second Army landed simultaneously.

Normandy beaches where Allied forces under British command landed (Source: 21st (British) Army Group, via Wikimedia Commons)

The 3rd Canadian Division, which included the 7th, 8th, and 9th Canadian Infantry Brigades, 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars, 1st Hussars and Sherbrooke Fusiliers, landed on Juno Beach in front of Courseulles-sur-mer along with the 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade. Eighteen-year-old Canadian soldier Joe Womersley, who trained with the 1st Battalion of the Black Watch in Scotland, landed at Juno Beach on D-Day. “We had some trouble coming in. I lost my gun in deep water and picked another one up and used that.”

The Canadians had the opportunity to move lead units off the beach quickly, but congestion was a problem at Juno as at other landing sites. The lack of serious opposition on the beaches, however, allowed the British and Canadian soldiers to move south and east toward high ground called Périers Ridge. The rise was a source of German anti-tank and machine gun fire. It was also the most defensible ridge between the beachhead and Caen, the largest city in the Calvados region where four of the five Allied landing sites were. Caen had a major intersection of roads, including the best road for tanks to advance to Paris. The Germans put a high priority on defending Caen.

Sections of Mulberry artificial harbor being prepared in England for towing to Normandy (Credit: Imperial War Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

The 3rd Canadian Division advanced three to six miles inland from the landing beach. Patrols from the 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade ran ahead as far as Bretteville l’Orgueilleuse, on the main road between Caen and Cherbourg. The penetration here was the furthest of any Allied force on D-Day. Private Womersley observed, “We fought quite a way up into the evening, and we ran into some stiff resistance.” Though the Second Army came within two miles of Caen and closed in on another smaller city to the west, Bayeux, British leaders were unsure of what they were up against. They postponed advances on the two cities until the next morning. This decision would turn out to be an unwise choice for the Allied Second Army.

The Germans Mount a Counterattack

The German leadership for northern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, OB West, was based in Paris. Within this command structure, Normandy was the responsibility of Army Group B under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had distinguished himself earlier in the war as commander of Germany’s vaunted Afrika Korps. (The Afrika Korps was wiped out in Tunisia in 1943, when Rommel was no longer in direct command.) Rommel was briefly sent to Northern Italy and then put in charge of improving the Atlantic Wall, the name given to the formidable German defenses along the coast of Western Europe.

The Seventh Army was assigned to defend the Normandy coast. The German High Command was convinced the Allies would invade the continent; they just didn’t know when or where. Complicating matters for OB West and Rommel was the fact that Adolf Hitler retained direct control over some German tank and armor forces (which were called “panzer” units after the German word for tank) in France.

The deception created by Lieutenant General George Patton’s fictitious army group operating on the English Coast opposite Pas de Calais, France, had most German leaders convinced the invasion would come there.

The panzer division closest to the Allied beachheads was the 21st. On June 6, it was first sent to the Orne River when British paratroopers landed in the predawn hours of D-Day. Then it was shifted to meet the sea invasion and protect Caen. The division moved to the vicinity of Périers Ridge and launched an unsuccessful attack against British tanks and infantry in the afternoon. This attack caused British leaders to delay advancing into Caen until June 7. By that time the new German defensive line was in place.

June 7 (D+1): The British and Canadian Advances Stall

General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, head of the 21st Army Group (which included the First and Second armies) and leader of the Operation Overlord ground campaign, had expected that Caen and the Carpiquet Aerodrome, on the western edge of the city, would be taken by British and Canadian forces on D-Day. That, of course, did not happen. The Canadians were again ordered to approach Carpiquet Aerodrome from their positions northwest of Caen.

On June 7, the German 25th SS Panzer-Grenadier Regiment attacked the Canadians near Authie. This German regiment was made up of well-trained teenagers from Hitler Youth and they fought hard. This action sent the Canadian 9th Infantry Brigade reeling. Over the next two days German attacks continued to bottle up the British and Canadian forces north and west of Caen.

To continue to keep the Allies from breaking out toward Paris, the German leadership shifted units and commands. Rommel ordered Panzer Group West to assume attacks on the Allied Second Army. Though technically in the Seventh Army sector, Rommel controlled the movements of Panzer Group West himself. He also ordered panzer divisions from the Fifteenth Army, which defended the coast from Le Havre to the Netherlands, to Normandy.

Panzer Lehr Division arrived first to help the 21st Panzer Division. Fritz Baresel was in the crew of a reconnaissance halftrack vehicle in the Panzer Lehr Division. “When the invasion started on June 6, 1944, we rolled towards the landing area. We hardly could move during daytime. The Allied air force was everywhere.” Other tank units followed, including the I SS Panzer Corps under Lieutenant General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich.

Members of the Canadian Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment and their M-4 Sherman tank (Credit: Captain Ken Bell, via Wikimedia Commons)

Throughout the week following the D-Day landings, General Montgomery ordered the I British Corps under Lieutenant General J.T. Crocker, which included the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, to continue attacks toward Caen. Sepp Dietrich’s panzers counterattacked and put the brakes on the Allied advance to the city. The lack of progress in this advance took its toll. The Canadian 3rd Division suffered a total of 2,831 casualties in six days.

Onward to Caen

Despite the determined attempts to move on Caen, General Montgomery’s critics could not understand his position on taking Caen. Was the stalemate a result of poor planning, timidity, or bad luck? The Allied air commanders were waiting impatiently for the ability to establish airfields in the level areas east and south of Caen.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces, wrote to Montgomery from England, stressing the strategic importance of taking Caen. Delays in supplies and troop arrivals caused by the Channel storm gave Montgomery pause, and perhaps the weather took a large share of the delay’s blame. The one thing Montgomery could say in his defense was that he was keeping most of the German Army in Normandy out of the American sector.

A major storm in the English Channel on June 18 and 19 disrupted Allied air operations and more importantly, supply operations. Huge sections of the Mulberry artificial harbor at St-Laurent-sur-mer were destroyed.

The troops of the Second Army had not been idle during the lull. Allied air operations made life uncomfortable for the German soldiers. British and Canadian artillery shelled the enemy without taking out any key targets.

Lieutenant Garth Webb was in charge of a four-gun troop in the 14th Royal Canadian Artillery of the 3rd Canadian Division. His unit landed in self-propelled guns and later switched to 25-pounder field artillery. Webb tells of the perils of advancing in the tracked self-propelled artillery vehicles: “Each individual gun in this invading group was a sitting bomb because on the surface of the gun we carried the ammunition for the gun, gasoline, [and] a lot of ammunition for the infantry.”

Having no success bypassing the medieval city, Montgomery decided a direct assault on Caen was necessary. As a preliminary step, he ordered Operation Windsor, to capture Carpiquet and the aerodrome there. The objective had eluded the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division since D-Day. The Canadians were again tasked with taking Carpiquet. The attack was preceded by a diversion of a squad of tanks from the Canadian 27th Armored Regiment, the Sherbrooke Fusiliers. At 5:15 am the attack began in bad weather with support from aerial rocket fire, Second Army artillery and the guns of the battleship HMS Rodney and the monitor HMS Roberts – 760 guns in all.

Hear the story of D-Day directly from five veterans of the historic invasion of Normandy in this MagellanTV documentary.

Opposing the Canadians was the 12th SS Panzer Division Hilterjugend, made up of dedicated 17- and 18-year-old Hitler Youth, as previously mentioned. Other SS panzer units were in the area. The Germans fired artillery, mortars and machine guns at the attacking Canadians. By 9:30 a.m., Carpiquet village was captured by Le Régiment de la Chaudière, the North Shore Regiment, and tanks from Fort Garry Horse (10th Armored Regiment). But at the airfield panzer-grenadier troops held out in concrete bunkers. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, backed by tanks and flamethrowers, could not dislodge the defenders. Members of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada tried to capture the control tower at the east end of the runway but were also unsuccessful.

The soldiers of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, after some gains, fell back when Panther tanks of the 12th SS Panzer Division approached from the east. Overnight, panzer-grenadiers attempted to retake Carpiquet village. The attack was not repulsed until 8:00 a.m. on July 5. The Canadians then only held the north part of the airfield, with enemy forces on three sides.

Canadian bulldozer cleans up rubble in Caen (Credit: Regional Council of Basse-Normandy/Canadian National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons)

Finally, on July 8, Charnwood, the operation to take Caen, began. At that time, the Germans abandoned Carpiquet Aerodrome. All of the Canadian units were involved in the fight. Allied troops entered the city on July 9. Another Canadian infantry division, the 2nd, arrived as fighting continued south and east of Caen.

Operation Goodwood and the Allied Normandy Breakout

One week later, Second Army launched Operation Goodwood to drive Germans from the plains southeast of Caen. Though hard fought, the success of this operation paid significant dividends. Combined with the American capture of Cherbourg, the First Army breakout from Normandy at the end of July, and the arrival of Patton’s Third Army, the Second Army’s advance southeast to the Falaise Gap trapped the Germans and disintegrated the Third Reich’s army in Normandy.

There was no question that the Canadian soldiers, as well as their comrades in the air force and navy, fought with great valor and spirit. After all, they were volunteers to the last man. And while their contributions and sacrifices on D-Day and around Caen were great, the Canadians took on an ever larger role after the breakout from Normandy. They were finally given their own identity and mission when organized into the First Canadian Army, responsible for clearing the French coast of V-1 and V-2 rocket sites, German armor, and infantry. Their mission culminated when they liberated the Netherlands and occupied the German coast in 1945.

Ω

Jay Wertz is an award-winning author, publisher, and filmmaker. He has written seven books, including four volumes in the War Stories: World War II Firsthand™ series. Other books include The Native American Experience; The Civil War Experience 1861–1865; and Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, co-authored with Edwin C. Bearss. He is the editor and a primary contributor to D-Day 75th Anniversary – A Millennials Guide and other works for Monroe Publications. He has been a columnist and online contributor for Civil War Times Illustrated, America’s Civil War, Aviation History, Armchair General, and America in WWII magazines. He is also the producer-director-writer of the documentary series Smithsonian’s Great Battles of the Civil War for The Learning Channel and Time-Life Video.

Title Image: Canadian soldiers walking ashore at Juno Beach (Credit: Regional Council of Basse-Normandy/Canadian National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons)