More than 500 geysers are active in Yellowstone National Park. Millions of tourists can attest to the beauty of these phenomena, but Yellowstone’s geysers also reveal chemical and geological processes that have contributed to life on Earth – and perhaps beyond our home planet.

◊

Approximately 640,000 years ago, clouds of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and water vapor filled the skies above Idaho. A cascade of ash and molten volcanic glass crashed down onto the earth below as the Yellowstone Volcano jettisoned 240 cubic miles worth of material from beneath the Earth’s crust. The viscous rhyolitic lava that oozed from the volcano eventually cooled, revealing the 40-mile Yellowstone Caldera we recognize today. The bubbling mud pots and kaleidoscope of colors on the edges of Yellowstone’s hydrothermals cast the National Park as a one-of-a-kind phenomenon, providing a lens into the goings-on far below our feet.

Yellowstone in a Geothermal Nutshell

Images of bison herds and wolf packs could make you think Yellowstone National Park today looks like Earth as it might have been millions of years ago, but that is not entirely accurate. Since its first major eruption occurred 2.1 million years ago, Yellowstone Volcano’s location in the northwest corner of modern-day Wyoming has seen thirty volcanic eruptions. Each explosion brought with it enduring changes to the makeup of the region, both topographically and biologically. New landscapes were formed by obliterating forests and toppling mountains with an icing of molten earth. And many species of wildlife were wiped out – and replaced over time by other creatures.

A herd of bison among some hydrothermal mud pots in Yellowstone. (Credit: National Park Service/ Diane Renkin)

A herd of bison among some hydrothermal mud pots in Yellowstone. (Credit: National Park Service/ Diane Renkin)

Magma Magnified

The hot spot beneath Yellowstone National Park continues to fuel geothermal activity across the caldera. While we might not hear about volcanic explosions on a regular basis, plenty of other features speak to the incredible power and heat stirring just below the surface of one of the most peaceful places on Earth. The continuing thermal activity of the caldera classifies Yellowstone as “an active supervolcano” and small offshoots of the hotspot’s subterranean power can be seen around the park today.

Hydrothermal Diversity

It is unlikely that a stroll around Yellowstone National Park’s trails will have you leaping over pits of lava and seeking shelter from a fiery ash storm. If you find yourself among the ranks of the park’s millions of yearly visitors, you are more likely to come across one of its 10,000 thermal features. Boasting the highest concentration of geysers, mudpots, fumaroles, and hot springs on Earth, Yellowstone offers an unparalleled look into the power of the heat beneath our feet.

The idea of taking a swim in a hot spring can get romanticized. But make no mistake, a dip in any of Yellowstone’s geothermal features is both illegal and unwise. With some pools rising to 200 degrees Fahrenheit, one wrong move can lead to severe burns and fatal nerve damage in a matter of minutes.

Vital Signs of Life Below

Networks of vents channel steam and build pressure far below the cones of hydrothermal features. The colorful pools that occasionally bubble on the surface have become hotspots for photographers over the years. Each geyser is different in almost every characteristic that defines it. Some spray water at angles and others straight up. Some geyser eruptions last for two minutes and others for 20. Some go off like clockwork and others take 50-year gaps before a streak of concentrated activity. If the park itself were an organism, hydrothermal activity across Yellowstone would serve as proof of life. The steady bubbling of mud pots beats with the pulse of the park, while the sporadic spray from Steamboat Geyser functions like a mighty exhalation.

Notable Yellowstone Geysers

Yellowstone’s glorious geysers are indicative of the volcanic activity below. Before a geyser erupts, inconspicuous pools of water lie still on the Earth’s surface. When enough steam builds up in the vents, pressure mounts and the water begins to boil, akin to kettle heating up. Eventually, the buildup of pressure bursts through the water in the pool above it, causing a cascade of mineral-rich steam to shoot into the air. Sometimes when a geyser reaches the point of erupting in a spray, nearby pools heat up and boil like the geyser’s pool had done. This indicates a connection that unites the complex network of hydrothermal features. As the largest hub of hydrothermal activity on the planet, Yellowstone boasts a remarkable array of geysers that offer insight into the incredibly complex system of vents and channels that heat up the hydrothermal features.

Old Faithful

A standout among the crowd of Yellowstone’s geysers is Old Faithful. As the name suggests, Old Faithful has a predictable schedule that can be timed down to the minute. While it is not the largest geyser based on the height of its spray, it is one of the most famous features of Yellowstone National Park for its predictable schedule that conveniently fits into many tourists’ timelines. Although its eruption interval has changed over the years due to changes in precipitation and seismic activity, over 100,000 eruptions of Old Faithful have been recorded.

Aerial view of Old Faithful Geyser. (Credit: National Parks Service/Jim Peaco)

The name of the world’s most famous geyser dates to the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition of 1870. When the group ventured into the Upper Geyser Basin, they had plans to survey features all across the region. Their journey followed the rim of Yellowstone Lake and led them down the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone. Throughout their exploration, the sound of a geyser’s eruption served as a slow metronome for their expedition. According to their records, the geyser “faithfully” spouted every 63 to 70 minutes, winning it the moniker Old Faithful.

Steamboat Geyser

Steamboat Geyser is reputedly the tallest active geyser in the world. In the rare instances when Steamboat geyser does go off, a stunning 300-foot stream of water shoots into the sky. After a 34-year period of inactivity, Steamboat began an unprecedented phase of activity in 2018, with 32 eruptions in that year alone.

Unlike Old Faithful or Riverside, which have steady eruption schedules, Steamboat’s erratic behavior is impossible for scientists to predict. The geyser was named in 1878 for the sound of its eruption, which resembles that of a steamboat setting out on the water. Despite its unpredictability, it would be hard not to notice Steamboat’s eruption when its steam can be spotted from miles away and its sound echoes throughout the Norris Geyser Basin.

Steamboat Geyser’s stream as seen from the Norris Geyser Basin Outlook. (Credit: National Park Service/Jacob W. Frank)

Castle Geyser

Taking its name from the dramatic formation of siliceous sinter deposits at the base of its vent, Castle Geyser is renowned for its remarkable shape. With eruptions occurring every 10 to 12 hours, this geyser can be recognized and admired for the thousands of years’ worth of silica build-up encapsulated in its towering base. When it does erupt, water spews out for 20 minutes before discharging steam into the sky for another 40.

Steam billows out from the silica mound of Castle Geyser. (Credit: National Park Service/Diane Renkin)

Many geysers across Yellowstone ought to have similar silica buildups, but, before protections were put in place, some tourists wanted to take a part of the park’s natural history home with them. These geyserites form from the silicon dioxide and minerals that are carried from below the Earth’s surface during an eruption. The formations create geothermically diverse ecosystems supporting a range of microorganisms that thrive in high temperatures. Preservation of these ecosystems has enabled scientists to study microbes that shed light on the evolution of archaeal, or single-cell, life.

Riverside Geyser

Located in the Upper Geyser Basin, Riverside Geyser shoots across the Firehole River at a sixty-degree angle, creating a prismatic arc when sunlight hits it just right. For 90 minutes leading up to its eruption, water levels around Riverside’s cone rise in tandem with onlookers’ collective anticipation of the oncoming spray.

Riverside geyser sprays water across the Firehole River. (Credit: National Park Service/Jacob W. Frank)

What Geysers Can Tell Us

The jury is still out on using geysers to keep time, but Yellowstone’s hydrothermal features still have a lot to tell us. As each geyser creates an opening into the geological goings-on beneath the Earth’s crust, it offers scientists a point of entry into the complex systems of seismic activity. The microbiomes that form in the extreme temperatures around geysers become home to a diverse range of microorganisms, the origins of which might inform us about hydrothermal activity well beyond our planet’s atmosphere.

Hydrothermal Networks

The remarkable and erratic activity of Steamboat Geyser has alerted scientists to the hydrothermal feature’s potential for revealing seismic developments across the entire Yellowstone Caldera. The nearby Cistern Springs’ water level seems to be directly correlated with activity in Steamboat, leading researchers to believe that two are interconnected.

Some say that Yellowstone’s supervolcano is ‘overdue’ for an eruption on an apocalyptic scale. Scientists continue to debate this theory, noting that volcanoes don’t follow a predictable pattern, so there is no way to know with certainty when such an event might happen.

By conducting probes of the Steamboat geyser and studying the related activity between the geyser and nearby water sources, leaders in geology are making headway in their understanding of eruptive behaviors. Drawing connections between bodies of water and how they relate to each other helps seismologists to make more accurate predictions about larger geophysical activity.

Geysers and Life beyond Earth

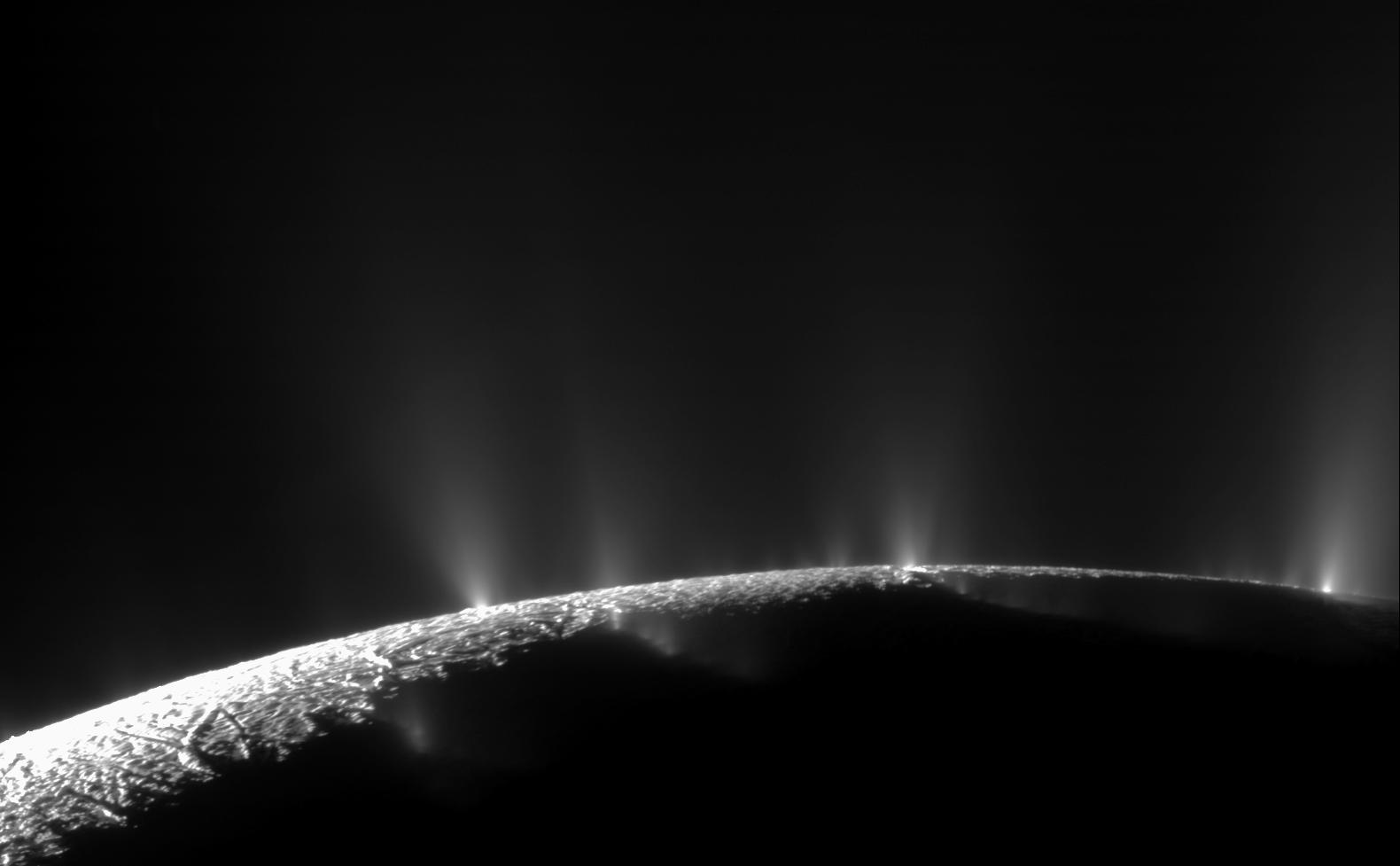

Geysers are not a hydrothermal feature confined to Earth. In 1989, NASA’s Voyager II spacecraft detected hydrothermal activity on Nepture’s largest moon Triton. A geyser’s eruption was captured by a camera on the probe, indicating the presence of frozen oceans lying beneath the moon’s surface. In the decades since, more planetary satellites across the Solar System have been discovered to have geysers.

Icy plumes from the geysers on the south pole of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. (Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute)

In 2019, a group of planetary biologists went to the Great Fountain Geyser in Yellowstone to examine how the conditions within geysers on Earth might be similar to those found on other planets. They explored how extremophile bacteria and archaea in boiling acidic or alkaline water could also survive in the extreme conditions found in the outer Solar System. The tiny organisms within the geysers that go unseen by the human eye provide scientists with clues about potential life on planets far away that might be invisible to us.

Experience the Yellowstone Geysers without the Spray

Images of the Yellowstone Caldera and its wildlife circulated around the U.S. Congress in 1872, and lawmakers found themselves enamored with the area’s stunning natural beauty. The testimony of those who had seen Old Faithful spray into the sky and watched the mud pots boil over convinced Congress that this area warranted protection.

Today, millions of people flock to Yellowstone each year to bask in the mists of the geysers that were crucial to the case for the creation of the United States’ first national park. The clarion call of Yellowstone’s geysers still trumpets their significance, even over the sound of Steamboat Geyser, should it decide to go off. To explore Yellowstone’s remarkable hydrothermal features, wildlife, and history, watch Yellowstone on MagellanTV.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. She also writes for Local Life magazine. Originally from Georgia, she graduated from Kenyon College with a degree in philosophy and studio art. She now lives in Chicago.

Title Image: Clepsydra Geyser in Yellowstone’s Lower Geyser Basin. (Credit: National Parks Service/Mike Goad)