Ludwig van Beethoven was among the greatest composers in history, yet he is often seen as a moody, dark genius. What underlies this long-lasting impression? By any measure, Beethoven had an unusually difficult childhood and a family life that was marked by respect for – and fear of – his erratic, overbearing, and frequently drunk father. Who were the Beethovens, and what effects did growing up in a family headed by a dominating problem drinker have on Ludwig and his development as a composer?

◊

A Commotion in the Night

Let’s begin with a story from the life of an ordinary, middle class family of its time:

It was near midnight in 18th century Bonn, a German archbishopric of the Holy Roman Empire. Johann van Beethoven had spent the evening regaling his drinking companions with tales of his son Ludwig’s awe-inspiring talent on the keyboards. To impress his friends, he gathered several of them and walked from the tavern to the comfortably appointed home where his family lay sleeping. Without warning, the silence was shattered by ruddy-faced Johann and his boisterous guests.

“Ludwig!” his father bellowed as he stormed into the child’s bedroom. “Ludwig! Up and to the pianoforte!”

It was not the first time Ludwig’s fitful sleep was disturbed by his father’s alcohol-fueled ranting. So, yet again, Ludwig descended the stairs in his nightclothes to play for the impromptu audience. Struggling to please his father and the others, he stood on a footstool to reach the keys.

As his son’s teacher, Johann was hardly a disinterested listener. Every time Ludwig hit a sour note, his father’s hands came crashing down on his son’s with a loud, discordant thwack! Johann demanded that his son start again, over and over, till he could play the piece perfectly.

The attentive (if somewhat inebriated) visitors could see tears welling up in young Ludwig’s eyes as his small hands stretched to reach the correct positions for notes, chords, and melodies. He was tired, afraid of his father’s rage, and determined to play well enough that his father would let him go back to bed. But it could be dawn before his father was finally satisfied – or too exhausted himself to continue.

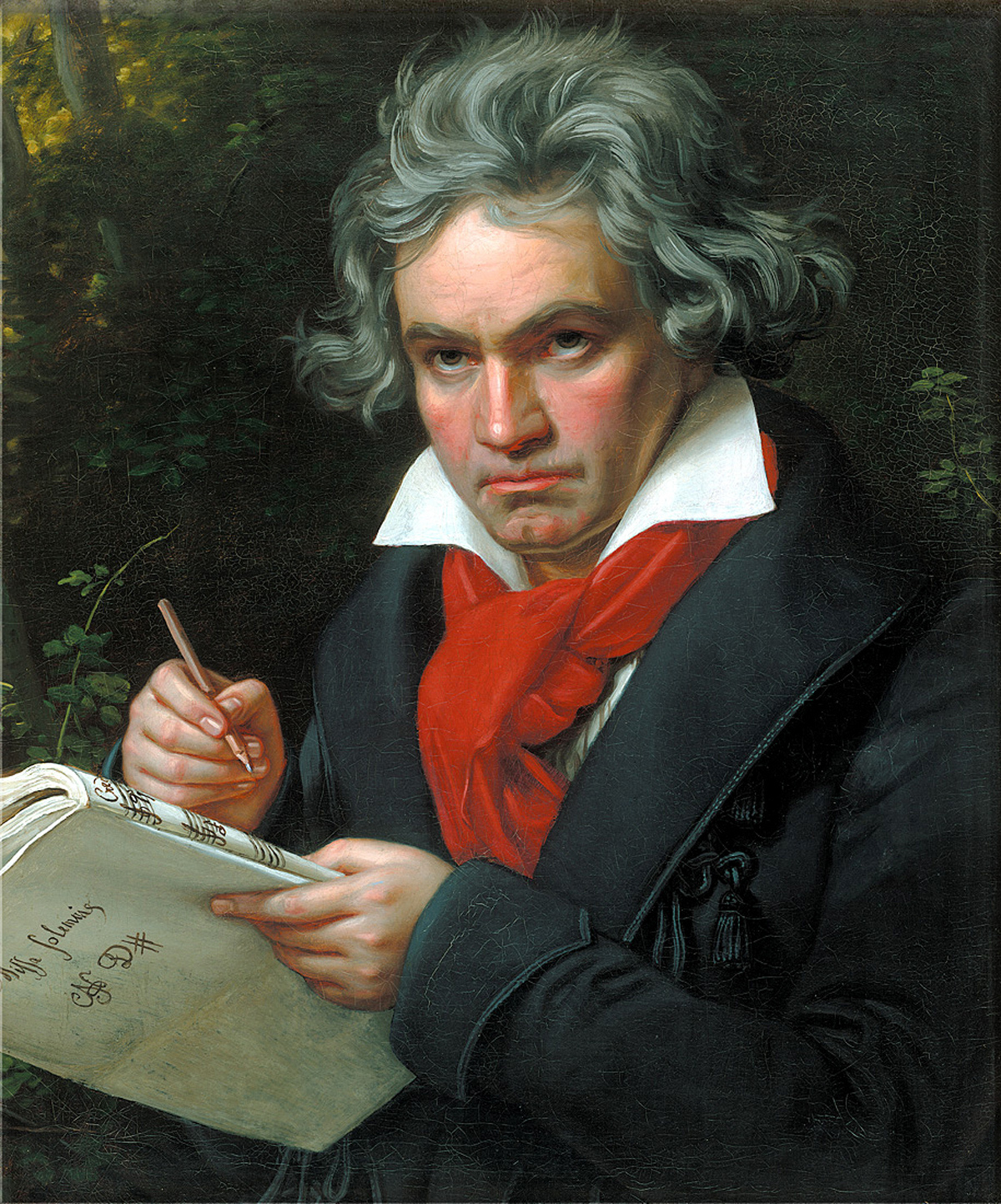

Beethoven at 13 (Source: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, via Wikimedia)

The Beethovens of Bonn

To children of alcoholic parents, the story of Ludwig’s midnight performance for his father’s guests may sound all too familiar. While it might not be accurate to the nth degree, we know that very similar scenes did, in fact, play out in the Beethoven home – just as they do today behind the curtains of many outwardly unremarkable residences.

The Beethoven family originated in the Flemish region of Belgium, but, by the late 1700s, they had established themselves in Bonn (now a part of Germany). Ludwig’s grandfather was a successful musician, a proficient bass soloist and choral singer who was elevated to the position of Kapellmeister, or music director, in the court at Bonn. Ludwig’s father Johann showed promise as a tenor vocalist and as a multi-instrumentalist, and he found a place as a professional singer and vocal soloist in the men’s chorus.

Johann van Beethoven was quite aware of the early career, in Salzburg, of a musical genius named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was only a few years older than Ludwig. Using Mozart as a model, he took over Ludwig’s musical education in a determined effort to nurture and promote his young son’s precocious talent. As a result, the younger Beethoven was forced to forsake a proper education in favor of his father’s home schooling and ’round-the-clock practice on the keyboard.

Johann loved his family, his church, and his career. So far, so good. But he had another serious love, a common one both in his time and today, and one that he tried to keep something of a secret – Papa Beethoven loved his liquor.

Demands on a Gifted Child Can Leave Lifelong Scars

The chemistry between a very young but prodigiously talented child and his overbearing, demanding, very physical and alcohol-dependent father is a volatile mix. It creates a dangerously unbalanced set of family dynamics, and a sensitive child is likely to carry these experiences of violence and coercion through an entire lifetime.

An article in Psychology Today lays it out starkly:

The alcoholic family is one of chaos, inconsistency, unclear roles, and illogical thinking. Arguments are pervasive, and violence . . . may play a role. Children in alcoholic families suffer trauma [and] carry the trauma like an albatross throughout their lives.

Does this modern description match the dynamics of the Beethoven family of the 18th century? I believe it does, but, for now, let’s focus on Johann’s behavior and its effect on young Ludwig.

In addition to his position as a working musician in the court of Bonn, the elder Beethoven was employed on the side as a music teacher, instructing young members of the royal court in both violin and keyboards. And he was insistent that his eldest surviving son, Ludwig, follow in his footsteps as a musician and teacher. The plan wasn’t unreasonable, as, from an early age, Ludwig demonstrated precocious talent on keyboards. But setting an achievable goal for his son to pursue wasn’t enough for Johann.

A Perceived Rivalry with Mozart

Johann was, it appears, enviously aware that Leopold Mozart had, only about 15 years earlier, promoted his son Wolfgang as a prodigy at the age of six. When Ludwig began to show truly impressive promise as a young musician, Johann saw an opportunity to offer up his son as Mozart’s equal, or even rival. To sharpen Ludwig’s talent, Johann embarked on a punishing schedule of keyboard instruction for his child.

Beethoven and Mozart both displayed musical talent – even genius – from an early age, but Beethoven was a slow starter by comparison. Ludwig had his first public concert at the impressively young age of seven, but by the time Mozart turned seven, he had already been composing high quality music for two years!

Beethoven’s first public performance (featuring the deceptively promoted “six-year-old” Ludwig, most likely calculated to draw comparisons to Mozart) was before the crowned heads of Vienna. The only problem was that Ludwig was already almost eight years old at the time. But the discrepancy was irrelevant to his father, who stretched the truth so much and so often that Beethoven for the rest of his life thought he was two years younger than, in fact, he was.

The harsh life of being an alcoholic taskmaster’s talented oldest son exacted a toll on Ludwig. Not only did he suffer through his father’s physical approach to musical education, but, it is said, he never received praise from him, either. No wonder Ludwig had the impression that he had not achieved enough to deserve applause.

Modern professionals in the field of substance abuse would surely recognize that these patterns of living under the often harsh discipline of Papa Beethoven are typical of alcoholic childhoods: home life can be chaotic yet also controlled to an unreasonable degree by the alcoholic parent. Expressions of parental love can come in sudden torrents – or sometimes be absent altogether. And, within this unpredictable environment, even gifted children suffer from lower self-esteem.

Beethoven’s Early Achievements in Music

Having an erratic, alcoholic father could not have been easy for Beethoven and his family. With a beloved but retiring mother and two younger brothers, Ludwig felt a responsibility as the eldest son to ensure the family’s welfare, or at least to make up for Johann’s lapses. This, too, is a common trait among children of alcoholic families, who can vacillate between feeling powerless over their surroundings to feeling prematurely burdened by the heavy responsibilities of adulthood.

Around the age of eight, Ludwig commenced his study of composition. A few years later, in 1783, he completed a set of original keyboard variations on a march by Ernst Dressler. Also that year, he published his first set of piano sonatas, which were dedicated to the “elector” of Bonn (the archbishop who ruled the city-state), who was an early benefactor.

Mozart, just over a dozen years older than Beethoven and well established by this time in Vienna, cast a long shadow over the younger composer and musical performer. One of Ludwig’s dreams was to make a trip to Vienna in search of recognition and renown, as well as to study with the master – assuming Mozart was willing.

Finally, when he was only 16, Ludwig was permitted by his father to travel to Vienna on his own. Now he could pursue his own career plans, separate from his father, even though he felt the tug of his responsibilities to his dear mother and brothers. Despite those family considerations, he set out on his much anticipated trip to the musical capital of the continent.

Beethoven’s Vienna Sojourn Comes to Naught

Unfortunately, Beethoven’s ambitious plans for his time in Vienna crashed and burned, including his much-desired audience with Mozart. As it happened, his visit was cut dramatically short by news of his mother having taken ill. Ludwig was deeply aware of his family duty, as many children of alcoholics are, and he returned to Bonn without delay. Upon arriving home, he stayed at his mother’s side as her illness progressed and she quickly passed away.

Just think of what might have been! Suppose Mozart had heard the 16-year-old Beethoven’s early work, had been reminded of his own career as a child composer, and had been moved to invite the younger maestro to study, or even collaborate with him. Tragically, when Beethoven could return to Vienna, five years later, Mozart had already died.

The sad transition in the Beethoven family order caused the 16-year-old to redouble his efforts to supplant his errant father, whose drinking took a turn for the worse after his wife died. Johann, whose grasp of family finances was, even during the best times, unsteady, lost his ability to keep the family afloat. To make matters worse, Johann’s drinking had ruined his voice and he was no longer able to perform. Teaching became his sole source of income.

Matters became so desperate that Ludwig, at 18, was forced to petition the Elector of Bonn, Johann’s employer, to pay a full half of Johann’s earnings directly to Ludwig to maintain the family’s financial well-being. It would be another three years, when Beethoven turned 21, until he was able to return to Vienna and settle in.

Beethoven’s Solitary, Tormented Adult Life

One can only imagine the pressure felt by Beethoven as he confronted the loss of his mother, the unhappiness visited upon the family by Johann’s drinking, and the requirement to care for his younger brothers. Pressure and isolation, for his social life had been stunted by his father, and he now had the responsibility to look after the whole family – including his needy and dissolute father. Sadly, this is not an uncommon burden for children of alcoholics, as concern for their family’s well-being can translate into crucial yet overwhelming duties that are often perceived as essential to keep the family afloat.

Beethoven always felt the weight of this responsibility. Maybe this explains, in part at least, why he never married, despite his evident wish for female companions. His domestic responsibilities may have been too preoccupying, or perhaps the example of his parents’ unstable relationship was too much with him to permit the intimacy of romance and marriage. One thing we do know is that adults from alcoholic families carry through their lives the trauma of their childhood. This frequently leads to difficulties in forming healthy relationships; higher rates of anxiety and depression; excessive feelings of responsibility; and, as one might guess, an increased susceptibility to alcoholism later in life.

Though Beethoven never found a life partner, he frequently became infatuated with women he came to know. One legend is that no woman could live up to his idealistic quest for ultimate beauty. Whatever the reason, Beethoven was filled with longing, regret, and a deep desire that was expressed in the powerful emotion of his music, particularly such beloved Romantic anthems as the Moonlight Sonata and the Appassionata.

Like Father, Like Son?

Beethoven had a reputation for being disagreeable, often antisocial, and even overbearing, not unlike his father. It isn’t hard to imagine the lifelong effect that the fraught relationship with his father had on Beethoven as an adult. Like Johann, he drank to excess and was sometimes found drunk and surly by visitors both in the daytime and at night. In fact, he often felt a need to apologize for his behavior, though he insisted that it was all in service of his muse. In a piece of writing, the “Heiligenstadt Testament,” he composed an apologia of sorts for his boorish behavior:

O you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you and I would have ended my life — it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me.

What was this “secret cause”? Some readers might perceive in his words an allusion to his growing deafness. But I think there might be something else to which he’s referring. Perhaps, despite his obvious musical genius, he understood the trauma visited upon him in youth and the social limitations it imposed on him.

Let’s return to the pages of Psychology Today:

[A]dult children of alcoholics “have issues with control.” That means they are afraid of others and have problems with intimacy; they harbor anxiety . . .

We see these traits clearly expressed in Beethoven’s life. And yet, because of – or despite – it all, he created some of the most stirring, memorable music of all time. He created an immense body of work, compositions that are celebrated to this day, and probably will be forever.

A Tragedy of Trauma and Genius

Beethoven was a genius not just for his era but for all time, but would his prodigious talent and the deep emotions of his interior life have been revealed to us had he hailed from a healthier family environment? We’ve seen how his childhood and adolescence were marred by an alcoholic father, and how those early life experiences affected him throughout adulthood. His father’s influence may have caused him to become unapproachable, dark, and moody, but that very same father’s relentless approach to Ludwig’s musical education also might have unleashed in Beethoven the restless intellect and creativity that produced timeless masterworks such as his nine symphonies, capped by the eternally moving “Ode to Joy.”

It may be impossible to uncover the profound mysteries and secrets of creative genius. Perhaps we should simply be grateful that great works of art come into the world at all – whether their genesis is in ecstasy, agony, or just plain hard work. I think, though, that it is fair to discern in Beethoven’s early life the roots of the powerful emotions and astonishing musical achievement of his adult masterpieces. Johann’s treatment of young Ludwig was unforgivable, but, ironically, that behavior might have been the gift that released in Beethoven the musical genius we so admire. The music finally arrived both despite and because of the drama, and the trauma.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Silhouette of Beethoven at 16, 1838 (Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)