Despite knowing so little about it, we mark death with extraordinary rituals that reveal our beliefs about what it means to live.

◊

Who would’ve thought that throwing a handful of dirt on your brother’s body would be so meaningful – both for you and the king who had forbidden any burial service? Antigone, the protagonist of the eponymous play by Sophocles, draws King Creon’s ire with that fateful gesture.

From cremation to jazz funerals, and from sky burials to bone turning, there are death rituals around the world. From these rituals, we can infer that death is as significant as life. Why? Surely, once gone, the dead person can’t care about what happens to their remains.

So, why go through elaborate ceremonies or, in those instances where the dead are buried, spend thousands of dollars for a luxurious coffin? (Why, yes, there is a 14-karat gold casket that costs $200,000, and it wasn’t made for an ancient Egyptian pharaoh.) The answers to the question are as varied as the cultures, traditions, and faiths of the bereft. Let’s take a look at a small selection of the customs and the beliefs that underlie them.

Learn about different Asian death traditions in this compelling MagellanTV documentary.

Death Rituals

Three immediate reasons for death rituals come to mind: The living express their love and respect for the dead in ways that are meaningful within a certain religious or cultural tradition. The living use rituals as expressions of and vehicles for the enormity of grief. The living carry out the dead’s wishes, perhaps out of love and respect, or perhaps out of tradition.

Whatever the reasons, death rituals are symbolic gestures intended to convey something beyond the actions themselves. They are imbued with meaning that is not otherwise connected with the action. Think about it this way: A mark on a page is a squiggle, but you and I take it as a symbol – a mark that stands for something meaningful, in this case, a letter:

A death ritual provides a common language for the community. By engaging in specific rites, community members understand what has happened and what it means. Beliefs about death influence our beliefs about how to live, and vice versa. In each ritual, we find beliefs about death – what it is, and therefore what we can expect when we die.

Russian Orthodox Funeral Service (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Russian Orthodox Funeral Service (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Some believe death is a state of being that includes illness, old age, and sleep. As such, it’s consistent with life itself. Some believe death is the negation of life as we know it. Within that category are those who view death as the annihilation of life, after which there is no existence of any kind; those who view death as a transition to another existence; those who believe in multiple deaths and rebirths; and those who believe the dead and the living are in continuous engagement with each other.

Whatever we believe about death – and life – the rituals are complex. While we tend to focus on the emotional effects of death, it is clear the rituals discussed here are often deeply influenced by practical considerations.

Intercultural Handful of Earth, Cremation, and Burial at Sea

Throwing a handful of dirt on a casket that is being lowered into the ground is an expression of the belief that the body is returning to the earth. Cremating a body is often chosen over burial for myriad reasons. Some of those reasons include cost, space, and religious practice: Cremation tends to be less expensive than burial. Burial real estate may be limited. Finally, some religious traditions prefer cremation over burial, and some others have become more accepting of the practice.

A common funeral practice in the United States (Credit: Adobe Stock)

A common funeral practice in the United States (Credit: Adobe Stock)

In some cases, limited burial real estate leads people to opt for burials at sea, but there are other reasons. For example, some with an affinity for the ocean may choose to be buried at sea. In addition, like some who choose cremation for financial or environmental reasons, burial at sea can be less expensive and more environmentally friendly than land burial.

Buddhist Sky Burial

The Buddhist Sky Burial, practiced by the majority of Tibetan Buddhists, involves a literal return to the earth with nature’s help. In this practice, the body is left outside, often on a hilltop, not only exposed to the elements and various creatures, but cut into pieces to facilitate the process. Birds of prey, like vultures, and other scavenging animals are then called to consume the body.

Malagasy Turning of the Bones

The Merina Malagasy of Madagascar exhume a loved one’s entombed body approximately six years after death. Burial clothing is stripped and the body is re-wrapped with a fresh piece of cloth, after which the family re-inters the body for another five to seven years. The ceremony, known as the turning of the bones, is also called dancing with the dead. It is only after the body has fully decomposed, according to the tradition, that the spirit is released from the realm of the living. Hence, the ‘turning,’ which is thought to speed up decomposition.

South Korean Burial Beads

Limited burial space means that corpses are often cremated. In South Korea, some families have memorial beads created out of their loved one’s ashes. The process involves melting and then solidifying the ashes into crystals.

Afro-European Jazz Funeral

New Orleans, Louisiana, is famous for its jazz – and maybe even more famous for its jazz funerals, which are mostly commemorations of musicians. The Jazz Funeral serves as a sort of consolidation of both mourning and celebration. After a funeral wake at a church or home, a procession takes the body to the cemetery. Family, friends, and the brass band constitute the “first line” of the parade, led by a parade master in fancy dress.

Second line at a New Orleans jazz funeral (Credit: Wikimedia)

Second line at a New Orleans jazz funeral (Credit: Wikimedia)

Once the body has been interred in a crypt (the water table discourages below-ground burials in New Orleans), the funeral band’s music changes dramatically to reflect a celebration of life. At this point the raucous music inspires dancing, and onlookers are encouraged to join the “second line” of the parade.

Hindu Pyre Cremation

Along the Ganges River is a holy site bustling with activity in support of Hindu cremation practices. The corpse is swathed by family members in colorful fabrics, and after religious rites are observed, corpses are carried on a bamboo stretcher to a cremation pyre made of over 1,000 pounds of wood. Hindus believe that the cremation facilitates the release of the soul from the body.

Navajo Swift Burial

Navajo beliefs about spirits drive the nation’s traditional death rituals. Someone whose death is imminent is dressed in their best clothes, so that they are ready for burial when they die. This is one way that the Navajo avoid contact with the dead, whose swift burial reflects the traditional Navajo belief that spirits should not linger. Erasing the deceased’s footprints and burying their possessions are ways to facilitate the spirit’s departure. Even the four-day mourning period is structured to avoid re-calling the spirit. For example, overt displays of grief during the mourning period are discouraged.

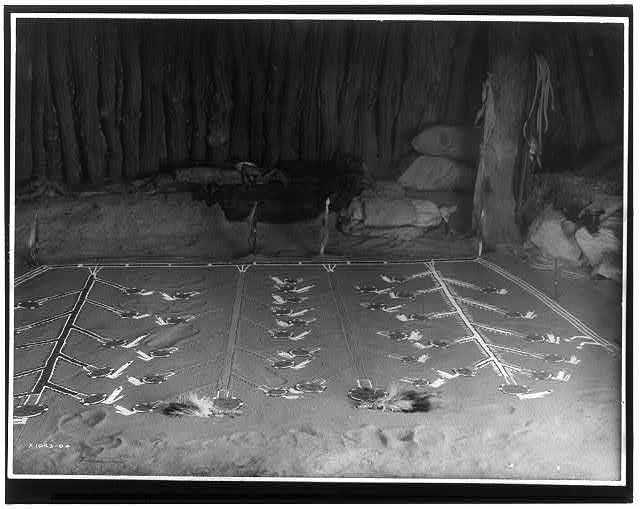

Navajo Sand Painting (Credit: Edward S. Curtis Collection, Library of Congress)

Various purification and mourning practices occur after burial, such as immediate family members cutting their hair, creating sand paintings, and participating in sweat ceremonies. The burials themselves are as far from the deceased’s home as possible, and historically involve placing the body in a rock crevice or tree, covered by brush and stone. Contemporary practices include cremation, but consistent with the belief that the spirit should not remain with the living, the deceased’s ashes are never spread.

Non-Religious Wake

Whether religious or not, the most famous wake is likely the Irish variety. Family and friends gather at a home or a funeral home one to three days before the funeral. An open casket allows visitors to pay their respects, and food and drinks are typically served. People play music, sing songs, and share stories about the deceased. After the funeral, mourners return to the home or pub to toast the deceased.

If I Don’t Think About It, Death Doesn’t Exist

In some cultures, particularly in the West, death is often an afterthought. There are bills to pay, places to go, friends to see, and work, work, work. In fact, for many, death is something to be feared and generally avoided, rather than a natural – albeit mysterious – process integrated into life events. As a result, talking about death can be difficult, like discussing Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders or organ donation with a loved one.

Do Life and Death Give Each Other Meaning?

Those who would rather not think about death, and who also live in a culture that views death as taboo, may think that death is non-existence. Life is good, which means death, as the privation of life, is bad. But how can this be?

You know those sayings, like “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” and “There can be no good without evil,” (or song lyrics, like “You don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone”)? What they all have in common is a belief that opposites are required for us to appreciate the good things in life. If you accept this dualistic view, does it also follow that you can’t have life without death (and vice versa)? More importantly, does it imply anything about the quality of life and death?

.png)

Epicurus (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus tells us that “death is nothing to us.” That’s because we don’t experience it. So, it is neither good nor bad. Another ancient Greek philosopher, Socrates, argues that fear of death is “the pretense of wisdom … the appearance of knowing the unknown”. Death might be good, bad, or neither.

The fact seems to be that we don’t have anything to which we can compare life. There is a sense in which death is not part of my life. As the 20th-century existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre argues, “...death is never that which gives life its meanings; it is, on the contrary, that which on principle removes all meaning from life.”

Death either is or is not the annihilation of my existence. I may cease to be, even if the laws of conservation of energy and matter imply death is not the same as nothingness. (And there aren’t any good explanations of nothing!) Alternatively, I may persist in some way. But, assuming I do persist, would I even recognize myself as such?

Thinking about death rituals leads to some puzzling, most likely unsolvable questions: Just what is life, anyway? The two-part Jazz Funeral suggests that life, despite the overwhelming hardships people face, and the grief felt when life as we know it ends, there is plenty to celebrate. Does awareness of your own mortality influence how you live? The Tibetan Buddhist Sky Burial reflects the view that existence is one, so life is guided by the belief in the unity of being, which includes death. How could you survive your own death? This is a knotty question, but the concept of a soul or spirit runs across a number of burial traditions, including the Navajo Swift Burial and Malagasy Turning of the Bones. So, across the globe, even if it’s not clear how that survival is possible, there are plenty who believe it is real.

Should we even bother thinking about any of these questions in the first place? Yes. In fact, if death rituals teach us anything, they teach us that we care deeply about these questions – and more besides. They are fundamental to the human condition. Whatever we do, death, like taxes, comes for us all.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. Among her relevant publications are essays in Mr. Robot and Philosophy: Beyond Good and Evil Corp (Open Court, 2017), Westworld and Philosophy: Mind Equals Blown (Open Court, 2018), Dave Chappelle and Philosophy: When Keeping it Wrong Gets Real (Open Court, 2021), and Indiana Jones and Philosophy: Why Did It Have to be Socrates? (Wiley-Blackwell, 2023).

Title Image credit: Adobe Stock (generated by AI)