Credit is ubiquitous around the world. But how did credit develop?

◊

Poor Pat. A series of unfortunate events – a combination of happenstance and misguided choices – have left Pat in reduced circumstances. Out of a job, car repossessed, the eviction notice plastered to Pat’s front door like a scarlet letter, Pat can’t even call someone for help because the power has been turned off. Pat’s cell phone battery died, but the thing wouldn’t have worked anyway because the cellphone company just cut off Pat’s service. Overdraft notices from the bank could be used as tinder for the fire Pat’s going to need to keep warm this winter. Like I said, poor Pat!

Turns out, Pat is your neighbor. The knock at your door is followed by an utterly deflated Pat, who practically crumbles into your arms, sobbing. You’ve always liked Pat, who is a reliable, considerate, and generous neighbor. From everything that you’ve observed, Pat is industrious, not afraid of a hard day’s work, and volunteers in the community. Needless to say, you’re shocked that Pat has fallen on such hard times. Now, slumped in a chair over a cup of coffee at your kitchen table, Pat wipes away the tears. “I’m so embarrassed,” Pat says, voice quavering. “But can you help me out? I promise I’ll pay you back as soon as I can.”

What do you do? Suppose that you can loan Pat money. How much is enough, and what is a reasonable repayment expectation? Sure, you want to help, but you can’t afford simply to give Pat money. How do you decide if Pat is a good loan risk? What criteria do you use?

Find out how people get by on minimum wage earnings in this revealing MagellanTV series.

What is Credit?

Credit cards. Credit lines. Store credit. Car loans. Mortgages. People borrow money all the time. Individuals, businesses large and small, and governments all borrow money. But from whom, and how do the almighty Powers That Be decide who gets money, how much, and at what interest rates?

Let’s start with the word, credit, which derives from the Latin, meaning believe or trust. To have good credit implies that you are financially trustworthy and therefore believable when you say you’ll repay a loan. To buy on credit means you’ve arranged to pay, most commonly, a bank or a store, sometime after a purchase.

Today, individual credit – consumer credit – is far less about a particular sort of reputation than it is about a spectrum of trustworthiness. In other words, before lending and borrowing were systematized, it was more individualized, more intimate, more like the situation with Pat.

Back in simpler times – as far back as colonial America – merchants created a sprawling credit system that powered trade growth among the colonies, Scotland, and England. Prominent families in cities like Boston also created vast trading networks. Whatever instrument of credit was used, such as bills of exchange or bonds, the glue that held the networks together, and the oil that lubricated the machinery of credit, was trust.

Those who can’t get credit have long been vulnerable to predatory lenders. Today’s payday lenders and credit card companies that charge usurious interest rates can be traced back to early American merchants, businessmen, and even clergymen looking to make money. By the turn of the 20th century, debtors coined the term “loan shark.”

After the American colonists declared independence, banks also appeared on the scene. These banks, banned prior to independence, funded business ventures largely by purchasing merchants’ financial instruments, such as bills of exchange. Merchants were paid in bank notes, which served as currency before a national monetary system was developed.

We might think of this sort of agreement – or any business arrangement – as similar to the scaling of the trust involved in a restaurant owner serving a customer food before asking to be paid for it. The restaurateur assumes that someone coming into their business knows the rules of this particular game.

(Credit: Adobe Stock)

(Credit: Adobe Stock)

These and similar rules of business are rooted in trust. Communities in colonial America and the early United States were small. People knew each other well. Shopkeepers made judgments about extending tabs to community members. The shopkeeper, in turn, might need those people for character references in order to secure loans from merchants or bankers. What happened, however, when people didn’t know each other well enough to make their own judgments?

The Origin of Commercial Credit in the United States

By the early 1800s, as businesses grew and spread, the old practices became untenable. Suppose, for example, you were a creditor in a city, but the person seeking credit was from a rural area. You didn’t know the applicant and had to rely on what strangers said.

Next thing you know, you’ve got multiple creditors relying on indirect testimony about a number of applicants. Or you’ve got individual applicants seeking loans from multiple creditors who don’t share information.

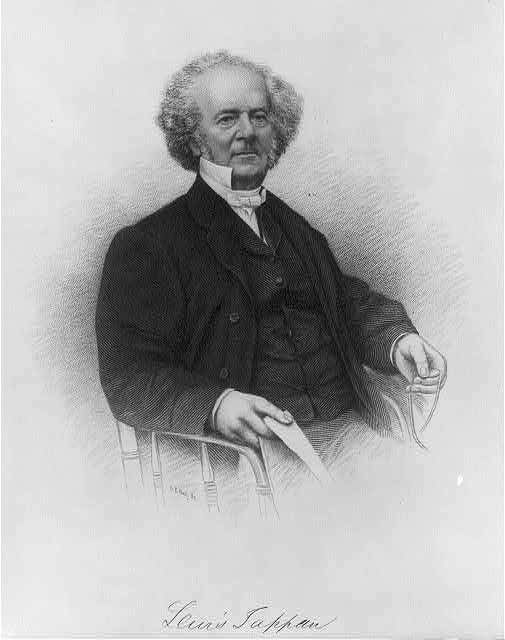

In 1841, Lewis Tappan created the Mercantile Agency to systemize what was heretofore an informal system of individuals vouching for each other – not in the domain of individual loans, but in business. What developed did, however, eventually impact what would become consumer credit.

Lewis Tappan was a fervent abolitionist who used much of his wealth to fight slavery. (Source: Library of Congress)

Tappan’s agency collected and organized information like a debtor’s character and assets. Less than a decade later, in 1849, John M. Bradstreet founded the Bradstreet Company. The company published the first book of commercial ratings in 1851 and, in so doing, popularized the use of credit ratings.

From Trust to Calculated Risk

The informal practices of ratings systems and information-sharing about consumers began taking formal shape at the turn of the 20th century, when retailers and credit managers formed a national association. Borrowing from existing practices used by commercial lenders, the National Association of Retail Credit Agencies streamlined their own metrics for consumer credit.

In 1859, Robert Graham Dun purchased Tappan’s Mercantile Agency, which then became R.G. Dun & Company. This company merged with John Bradstreet’s in 1933 to become Dun & Bradstreet, the business analytics company.

By the mid-20th century, the distinction between production and consumption sharpened considerably. Department stores and automobile dealerships were among the businesses that relied on rating agencies to determine lines of credit.

In some cases, credit enabled consumers to finance middle-class conveniences or to build the sort of wealth that propelled a family into the middle class. Consider home mortgages, which became part of the U.S. housing market in the 1930s. Before formalized credit, apart from businesses, only wealthy men could rely on borrowing schemes.

Is Credit the Great Equalizer?

In 1899, two brothers began the Retail Credit Company, which provided merchants a system for collecting and sharing consumer credit information. The firm’s files on debtors included relevant notes from merchants, such as whether or not the debtor paid on time. But they also included information on debtors’ personal lives, including political affiliations, social activities, and sexual habits.

The Retail Credit Company is now Equifax, one of the big three credit agencies. The other two are Experian and TransUnion.

Over the years, the line between relevant and irrelevant information was blurred by creditors (and, more generally, by social norms and laws). The Fair Credit Reporting Act, passed by Congress in 1970, was intended to clarify that line by protecting consumers’ rights to privacy, along with reporting accuracy and fairness. Even still, until 1974’s Equal Credit Opportunity Act, lenders could deny credit based on sex, race, and religious affiliation. What we now know as “redlining” in real estate transactions was, for example, preceded by lenders refusing to work with people like Black business owners.

(Credit: Adobe Stock)

(Credit: Adobe Stock)

It’s not difficult to see, given how the systematization of subjective judgments about credit worthiness would lead to inequities, that it would become a sort of surveillance system that doubtless influenced people’s lives. After all, credit reports determine insurance rates, utility rates, mortgage rates, interest rates, and so on.

Today’s big three credit reporting agencies continue to wrestle with aligning reports. The Fair Isaac Corporation, founded in 1956 by engineer William Fair and mathematician Earl Isaac, designed the algorithm to generate industry-standard credit scores. Your FICO score is determined largely by your credit history, which includes how long you’ve had credit, your payment history, and how much new credit you have.

It’s a Matter of Trust?

Today’s private sector credit reporting is a formalized system, but its origins are found in a basic human psychological state: trust. How is trust scalable? That is the core of credit – both commercial and consumer.

How do people make that initial leap to trust? Is it just part of our nature – are we naturally cooperative creatures, as the 19th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau has it? Or do we, as 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes thinks, have to overcome our suspicious natures – natures that would otherwise lead to “nasty, brutish, and short” lives?

In this context, thinkers like Rousseau and Hobbes want to explain the fundamental features of society, which leads to theorizing about the human condition – or human nature. Indeed, how we view ourselves (or are viewed) tells us a lot about our social roles, hierarchies, and so forth. Historically, for example, women were viewed as naturally nurturing, and obviously too emotionally unstable to participate in public life, while (white) men were viewed as protectors and providers.

(Credit: Adobe Stock)

(Credit: Adobe Stock)

Thinkers like Rousseau and Hobbes account for activities such as generating credit, by theorizing about human nature. That nature is benefitted or not by social contracts – agreements about how we formally organize ourselves into social bodies. For Hobbes, the uncertainty of the hypothetical state of nature drives people into cooperation – trusting others is a major risk, but worth it for the protection of a social contract. For Rousseau, on the other hand, inequality and a host of other social problems result from entering into social contracts – it’s not a safe haven.

Trust is inherently risky. After all, in a trust relation, one person depends on the other. Just how risky it is may derive from our view of human nature. Today, in the financial arena, it most certainly derives from the algorithms that make up our credit score.

A nod, a handshake, a verbal agreement, a written contract. All are expressions of trust. Society isn’t possible without taking the risk to believe another person. Back to Pat, whose FICO score is now in the toilet. Pat’s history before the fall is not even a distant memory to lenders. You’re it. What will you do?

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct faculty member at Salve Regina University and the University of Rhode Island. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. Among her relevant publications are essays in Mr. Robot and Philosophy: Beyond Good and Evil Corp (Open Court, 2017), Westworld and Philosophy: Mind Equals Blown (Open Court, 2018), Dave Chappelle and Philosophy: When Keeping it Wrong Gets Real (Open Court, 2021), and Indiana Jones and Philosophy: Why Did It Have to be Socrates? (Wiley-Blackwell, 2023).

Title image credit: Adobe Stock