What does it mean to be a citizen? The concept has developed since ancient Athens created the first known democracy.

◊

True story: I walked into a bar in Providence, Rhode Island, to find a guy sitting in a chair in the middle of the room getting a haircut. Everything was professional-like, smock and all. After a little though, I decided it made sense. All you have to do is clip the last three letters from “barber.” Though it’s impractical to try to sip your beer while hairs are flying around your head, you get the social benefits of two disparate activities at one location. People like to jaw, whether they’re bellied up to the bar or sitting in the barbershop chair. Besides, so far as I can tell, there’s no law against having a barbershop in a bar – you just gotta be licensed.

Ah, freedom. Liberty. It’s one of the great things about citizenship in a self-governing society. For most of us, freedom typically comes to mind when we think about our citizenship, whether we’re in the United States or Canada, Chile or Brazil, Australia or India, or Taiwan or South Korea.

But is this really what we mean by liberty? Our freedom isn’t unbounded, even if we’re not clear on where the boundaries lie. That’s partly because, in a civil society, freedoms are legally enshrined rights, and we don’t always agree on what counts as a right.

Complicating matters is how democracy is formalized. For example, a democracy can be direct or representative – and sometimes both. In the United States, citizens of a city or state often vote directly on laws, but they also elect representatives at the city and state levels. And, while democracy is the most common form of government today, not every democracy is recognizable as such. Turkey, for example, has elements of authoritarianism, which diminishes fundamental features of citizenship.

So, what does it mean to be a citizen? Is it having your freedom legally protected from governmental interference, or is it having the obligation to participate in political life? As we will see, the answer depends largely on how societies have conceived of the self – of what it is to be “me.” In modern and contemporary democracies, my identity as a free, rights-bearing person is legally protected from interference. In ancient Athenian democracy, on the other hand, my identity was defined by my role and activities in the community.

Mary Beard takes a deep dive into the lives of Roman citizens in MagellanTV's Meet the Romans: Citizens of the Empire.

Citizenship and Ancient Athenian Democracy

Around the 5th century BCE, the ancient Greeks – specifically, the Athenians – developed the first known democracy. Adult citizens were required to participate in politics – the life of the city, or polis. Indeed, citizenship was inseparable from the life of the polis. Political life, however, restricted citizenship to free men over age 20 – no slaves, women, or children allowed.

The English word “democracy” derives from the Greek demos (people) and kratos (rule). But the Athenian system of democracy was direct. The oldest form of representative democracy dates back to the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy in the 11th century, which later influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Though Athens’ view of non-citizens is elitist, the way Athenians thought of citizenship within the scope of the free male population was progressive. Your social status and property ownership, for example, did not factor into your eligibility for citizenship. In fact, most citizens were farmers and artisans. Instead, Athenian citizenship was determined by birth. If your parents were Athenian, so were you. (While Athenian women could not participate in the political process or serve on juries, they could own property and were active in the public religious practices crucial to the life of the city.)

Drawing a boundary around eligibility to participate in shaping the community effectively meant valuing the public domain over the private, or the domain of self-ruled men over everyone else, even if that rule was thought to benefit the entire community.

Of the total Athenian population, 40,000 were citizens, and about 7,000 were actively engaged in civil or military affairs at any given time. They rotated service in the institutions that implemented the laws they or their countrymen passed, such as the Council, which consisted of 500 citizens. All citizens could attend the Assembly, where they could speak and vote.

Plato and Aristotle on the Virtue of Citizenship

Not everyone in ancient Greece was a fan of democracy. Plato, for example, loathed the Athenian democracy that killed his beloved Socrates. The unjust execution was evidence of how dangerous an ignorant citizenry can be. This is an instructive point, for Plato links a good government with the common good, which is advantageous to all. Another way to put it is that justice is the condition toward which both individuals and the political order strive.

To know what that good is, according to Plato, requires the careful cultivation of one’s rationality – more specifically, one’s ability to grasp universal concepts like Beauty, Virtue, and Justice. Not everyone has the aptitude to be a city’s guardian. Only the wisest should rule, and they should do so not to satisfy their own desire for power, but rather to benefit all citizens.

In his Republic, Plato argues that timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny are all unjust types of government. Only the rule of the best, which for Plato requires knowledge of how to benefit those who are ruled, is just.

So seriously did Socrates take citizenship that he refused to flee Athens after his conviction for not worshiping the state gods, creating new divinities, and corrupting the youth – knowing that he would be executed. Though unjustly convicted, Socrates argued that he would not commit an unjust act in return by escaping. For Socrates, the good life is intimately connected with citizenship, which is inextricable from an examined life. Were Socrates to have left Athens, he would also have left his citizenship behind.

Jacques Louis David’s “The Death of Socrates” (1787); collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Plato’s student, Aristotle, picks up this important thread in a primer for the young man preparing to enter political life. Indeed, for Aristotle, men are “political animals,” because they are social creatures. The city-state is the natural place, then, for actualizing their humanity. It is as a citizen, then, that the individual can realize the good life. Through participating in public life, by ruling and being ruled, the citizen makes society good and is made good himself.

We can see from this sketch that the quality of a citizen’s character – how he communicates, reasons, responds to the vicissitudes of life – is central to a successful democracy. The good life can’t be achieved without each citizen pursuing and practicing excellence or virtue (arête). This excellence is pursued not just in legislative activities, for example, but also in religious rites, social clubs, and art; the life of the city thereby brings even non-citizens into the political fold. (Women, for example, held religious offices.) In a significant way, then, ancient Athenians saw little difference between the cooperation of individuals in a society and the obligation demanded by the city-state, even if not every member of the community could be a citizen.

The Acropolis in Athens (Credit: Mark Cartwright, via World History Encyclopedia)

How the Roman Empire Changed Citizenship

Aristotle’s theory of citizenship is a republican model, which emphasizes direct civic participation, or self-rule. This model demands much of the citizen, such as knowledge of the political institutions and processes, and prioritizing the good of the whole over individual desires, even as it is a crucial feature of that individual’s identity.

It turns out, however, that what theorists call the republican model is not scalable. Although the population of Athens was large relative to other city-states (upwards of 300,000 at its height in the 5th century BCE), it was still small compared to many of today’s societies. Smaller communities were better able to manage the sort of direct participation in city affairs characterized by Athenian democracy. Not only are current societies much larger than ancient Athens, they are also more complex. The idea of how you’d go about rotating civic duties, for example, is unwieldy, at best.

Labeling citizenship as republican or liberal has nothing to do with political ideologies or forms of government. Instead, they are terms used by theorists to distinguish models of citizenship.

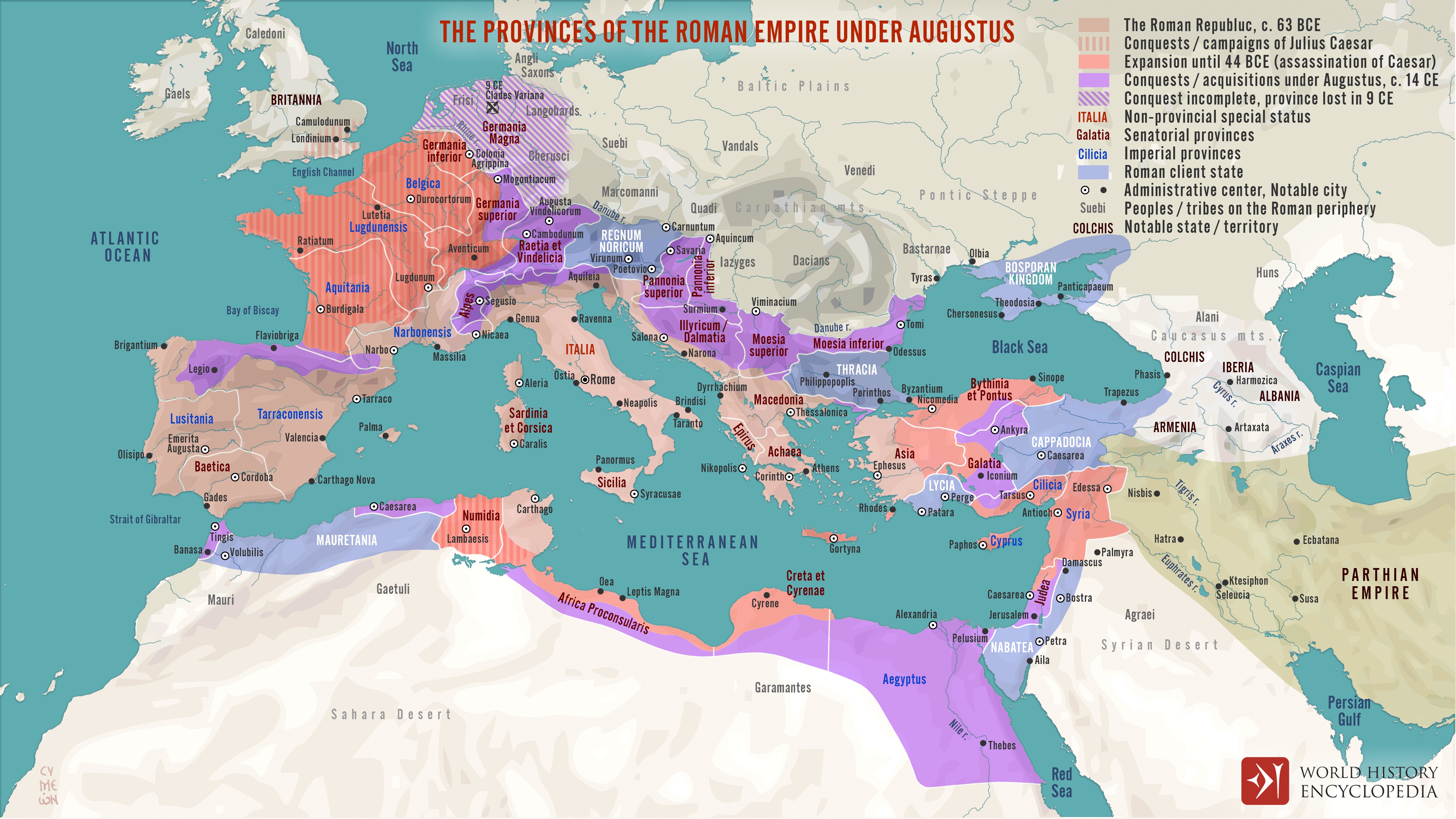

Today’s thinking about citizenship in liberal democracies largely reflects a different model that has its origins in the Roman Empire. As the empire expanded, Rome extended levels of citizenship to people in conquered territories, which transformed the concept of citizenship from active participation in political offices and processes to a legal status.

That status meant the individual had the protection of Roman law, which also thereby meant the citizen had certain rights. If you were not allowed to vote, but you were allowed to marry a freeborn woman and engage in commerce, you’d cultivate the aspects of your identity open to you by law.

(Credit: Simeon Netchev, via World History Encyclopedia)

In 212, C.E., for example, when Emperor Caracalla gave Roman citizenship to all free men in the empire, the concept of citizenship had already begun to change from the republican model. The gradual and selective shift can be seen in granting citizenship to non-citizens who had completed long-term military service.

The cloak of legal status, rights, and the attendant shift in thinking about identity opened up the implicit distinction between the public and private realms of life. The public becomes associated with the legislative and administrative community, while the private becomes a sort of sacrosanct space of freedom. So, the idea of citizenship is one in which active participation in shaping the community morphs into active participation in private life and social endeavors under the protection of law.

Republican vs. Liberal Models of Citizenship

These shifts can be seen in the development of England’s Magna Carta in the first half of the 12th century CE, which placed law above kings; in 1778, when the U.S. Constitution was ratified; and the following year, 1789, when the French National Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

By the late 18th century, European thinking about the individual focused increasingly on free agency, and so was solidly associated with rights – freedom from governmental interference in private life and freedom to pursue one’s own interests. Active participation in political life retained the echo of the republican model in some liberal democracies, at least in terms of the privileged classes running the show, but identity and citizenship were no longer inextricably linked.

The development of the concept of citizenship was not uniform. For instance, although Rousseau (1712–1778) advocated a republican model in The Social Contract, it is the citizens who create their freedoms and their laws, for they are not subjects of a monarch but political agents whose will must be directly expressed.

Recall that in the republican model, identity is bound up with civic life and the common good. In the liberal model, we might say that identity precedes community, insofar as that identity hinges upon membership in that community – and in particular, my legal status as a citizen, which confers various rights and privileges. In short, republicanism emphasizes a citizen’s obligations to political life, while liberalism emphasizes a citizen’s freedom independently of that life.

(Credit: Nick Youngson, via Blue Diamond Gallery)

Citizenship, Identity, and Community

Like any human endeavor, democracies are fragile and dynamic. They require care – it’s not enough to think that agreed-upon rules or founding documents are self-sufficient. Citizens of today’s liberal democracies are confronting complicated challenges to the very concept of citizenship, such as globalization, immigration, borders, and rights. That’s because citizenship is, at bottom, a question about the relation between identity and community. How do I be with others? It’s a question that informs our thinking about rights. What claims do we have on others? What do we owe them?

Implicit in those questions is the concept of liberty, the freedom to pursue our own interests without interference. Here again, we are confronted with challenges, such as how far our liberties extend before they interfere with another individual’s freedom. It may be that taking the time to carefully examine what we believe about citizenship will direct our future rights and freedoms – or lack thereof.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct instructor at the University of Rhode Island, Community College of Rhode Island, and Providence College. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. She lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.

Title Image: 2018 People’s Vote march (Source: Wikimedia Commons)