“Propaganda” and “war” generally go hand in hand. After World War I, however, propaganda became a marketing tool no longer reserved for posters of the enemy and national spirit. It evolved to become the calculated manipulation of emotions and societal desires to psychologically influence a buyer to purchase goods. Like war itself, propaganda is calculated and formulated with an attack plan that includes allies and enemies.

◊

It’s nearly impossible to go anywhere without running head first into an advertisement. After all, we live in an era when our social media and email accounts end up looking like the Time Square of ads. Turn on the T.V., flip the pages of a magazine, or go for a drive, and you’re likely to get bombarded with commercials. We’re constantly being told what we need in our lives by people we’ve never met … and it works. But why? Does the term “propaganda” ring any bells? Propaganda may remind you of a weapon of war or a game of politics, but it has evolved into an all too familiar tool of today’s world.

Propaganda works by manipulating and exploiting our emotions and needs. It uses hopped-up slogans and plays on our hopes and fears to evoke a desired response. But when did propaganda begin to enter our homes and everyday lives? It all began with World War I. The end of this war brought about changes to the world. Included among those changes was the advent of a new kind of propaganda that reached far past political cartoons and slogans to influence our daily decisions.

Advertising The War

Nations at war have always sought to shape public opinion and morale, but it was during the First World War that propaganda became a huge tactical resource. Governments recognized the importance of propaganda and allocated significant funds and effort to produce these materials. Publications, posters, films, and speeches were crafted to influence societal opinion on war, and contributing organizations began to pop up – one of the better known being Wellington House.

Formed in 1914, Wellington House was home to a secret cohort of journalists and editors whose sole purposes were to spread positive messages regarding Britain and to counter the propaganda of enemy countries. The materials distributed by Wellington House were so successful at swaying public opinion that the Chinese version, Cheng Pao, was credited with enabling the Chinese government to declare war against Germany.

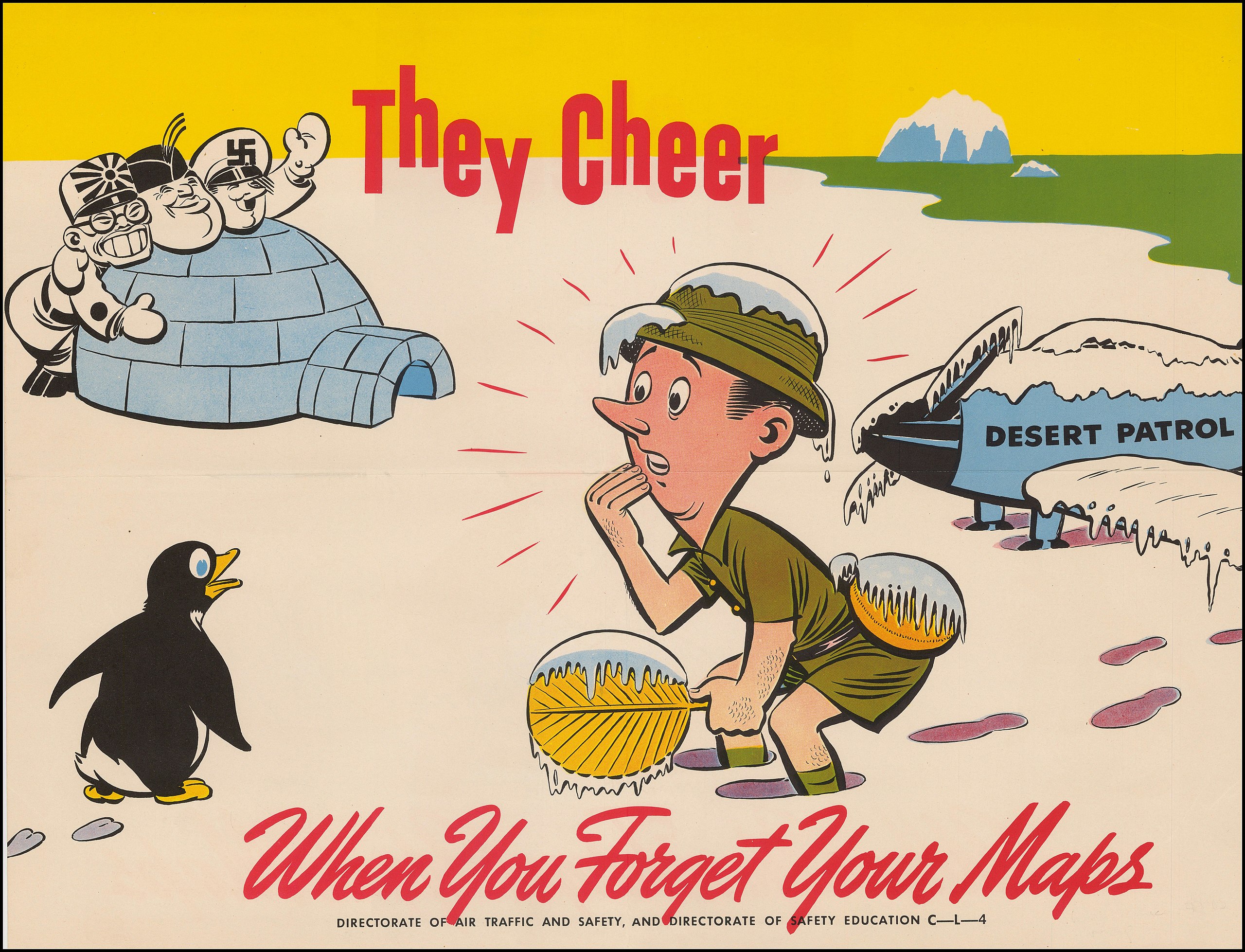

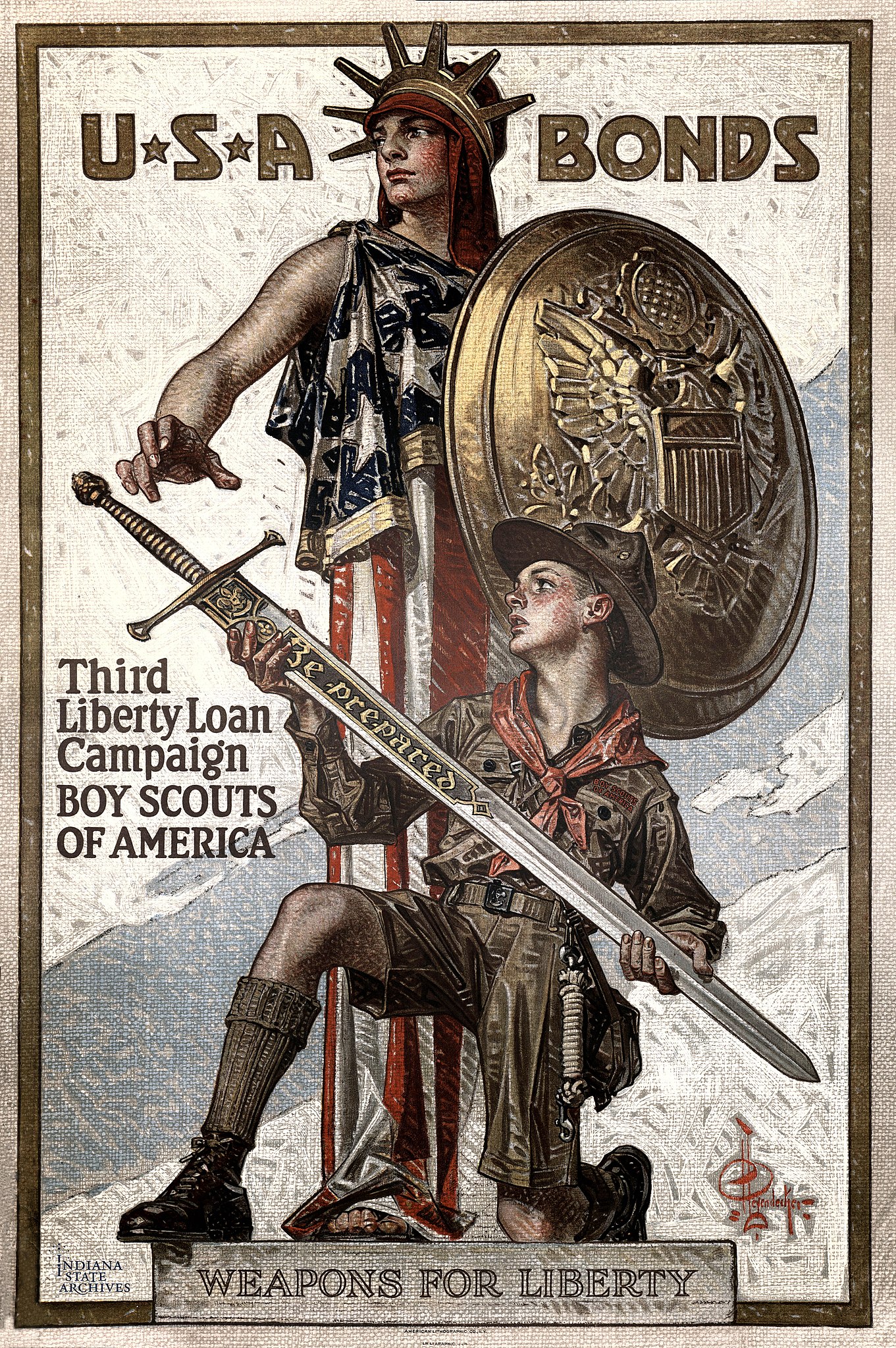

In addition to the publications distributed by Wellington House, artwork was also used to influence societies during the war. Propaganda posters were created to evoke sympathy for the viewer’s country and abhorrence of the enemy. Each side produced its own images: Allied forces portrayed Germans as barbarians, and Germans portrayed the allies as cruel and heartless.

British WWII propaganda poster, c. 1943 (Source: Directorate of Air Traffic Safety / Directorate of Safety Education, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Propaganda was effective. It could make citizens believe their home country was winning a war when it wasn’t. It could manipulate minds into thinking “enemies” were less than human. It was full of promise, and full of possibilities. But the potential of propaganda was not limited to wartime.

After the armistice ending World War I, the astounding success of propaganda left experts wondering “what next?” They weren’t about to lose their jobs just because the shooting had stopped. Equipped with a powerful tool, they imagined the possibilities for influencing public opinion in peacetime, too, and began to explore ways it could be used in everyday life.

Meet Ed Bernays, Propaganda’s Master Manipulator

Leading the efforts to apply the principles of propaganda away from the battlefield was Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud and a self-proclaimed “propagandist for propaganda.” Bernays began his lifelong career in propaganda during World War I, when he worked for the U.S. Committee on Public Information (CPI). After the war, he found a way to combine the knowledge he acquired from CPI with his family background in psychology by promoting propaganda’s use for political and corporate manipulation. He was so successful that he became widely known as the “father of public relations.”

“Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.” – Edward Bernays

In 1928, Bernays published his enormously influential book, Propaganda. In it, he employed the motif of an “invisible government” – an unseen power that exists to promote social, economic, and political trends. Bernays described this omnipresent “big brother” as having the ultimate goal of influencing the public and pushing them towards an opinion – and to act on it.

WWI U.S. War Bonds propaganda poster (Source: Boy Scouts of America, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Velvet Turns Propaganda to PR

What are the best brands? The most fashionable trends? The healthiest choices? I don’t want to be the bearer of bad news, but propagandists have decided all of these for us. Don’t believe me? Let’s take a look at the velvet industry.

Wait … Velvet? Yes, it seems like a random leap from war posters to soft fabrics, but the velvet industry holds the key to seeing the effects of propaganda on the market. After the First World War, textile manufacturers who specialized in velvet faced trouble – the fabric was out of fashion and appeared not to be long for this world. The velvet market took a devastating hit, and analysts deemed it impossible to revive in America. Yet propagandists, against all odds, brought the dying industry back through the power of suggestion and precise orchestration. But how did they do it?

Propagandists knew that Paris was the hot spot for fashion, so they created connections among the velvet manufacturers, Lyons manufacturers, and Paris couturiers. They encouraged Parisian businesses to create velvet wares, and then persuaded influential French woman to wear these designs. When American women saw Parisian socialites and aristocracy wearing velvet, they admired it. Voila! Velvet was back in vogue, and a new field called “public relations” was born.

We’re all familiar with the PR industry – we encounter it every day. The power of suggestion is their game, and they’ve been playing it ever since the end of the First World War. With the successful resuscitation of the velvet industry, propagandists were emboldened to manipulate the markets still further, operating under the banner of “PR.”

“New Propaganda” and the “Most Important Meal of the Day”

The fresh application of advertising was called “new propaganda” (which laid the groundwork for PR), and it shaped American – and international – markets far after World War I. The novel method was used not only to sell clothing but also to aid sales across the board from food to furniture.

Propagandists received support from manufacturers, influential individuals, and even physicians.

The “new” concept of salesmanship, as defined by Bernays, revolved around the understanding of the structures of society and principles of mass psychology. It focused on controlling group decision-making, instead of focusing on the individual. Bernays believed that the “masses” were controlled by herd instinct, and that people would act without much thought on their own. There is, after all, some psychological truth to the excuse, “But everyone’s doing it.”

Need an example? When you wake up in the morning, what do you do? Chances are you fix yourself “the most important meal of the day”: breakfast. Name a more iconic morning duo than bacon and eggs … I’ll wait. Since what feels like the beginning of time, these two items have taken the most important spot on your early morning plates. Sorry to say, that’s the propaganda talking. The idea of this ol’ reliable breakfast is actually a creation of recent history. The reason we have this notion of breakfast as the cornerstone to a great and healthy day is that the farming industry wanted us to believe it. Think I’m being paranoid? Well, it all goes back to our friend Ed Bernays.

During the Industrial Revolution, people were moving from farms to factories. A big farmer’s breakfast was no longer needed for the new way of life. Because of this, farmers were left with – you guessed it – a surplus of bacon and eggs. Edward Bernays picked up the campaign, and greased the public opinion on bacon. He got 5,000 doctors to sign a statement that a hearty breakfast was a healthy breakfast.

Hey, if a doctor says it’s healthy, it must be … right?

This kind of manipulation continues to the present day: “9 out of 10 dentists recommend …” and “the product doctors trust” are common advertising taglines. But how does propaganda really work?

This Is Your Mind … And This Is Your Mind On Propaganda

Propaganda has deep psychological roots, and there are reasons it shapes opinions. In 1956, Eunice Belbin, of Cambridge University, conducted a series of experiments on the effects propaganda has on recall, recognition, and behavior. The study investigated the nature of recall, and evaluated how individuals used recalled information – whether they knew it or not.

During the course of her study, Belbin displayed different road safety posters in a waiting room and observed the effects each poster had on its viewers. The effects were measured by 1.) the amount of information from the posters that was applied during the interpretation of photographs, and 2.) the amount of information included on each poster that could be recalled. The posters were viewed by a variety of people of all ages, and the results were measured. After 14 days had passed, subjects demonstrated the ability to use information from the posters even if they could not remember seeing it.

That’s the power of propaganda. Even when an individual cannot recall seeing something, he or she is still affected by it. In this case, individuals applied the information learned, even though they could not remember reading or seeing it. As Bernays put it, people “are rarely aware of the real reasons which motivate their actions.”

Life after Truth: Living with Social Manipulation

Whether or not we are cognizant of its effects, propaganda exists in daily life. We may not see Uncle Sam pointing his finger at us and proclaiming “I Want You” as we walk through Time Square, but we are bombarded with images that do want us. Billboards, store fronts, mascots, and restaurants: we pass by hardly noticing them, but we retain the messages. And, like it or not – whether we realize it or not – we are manipulated. Your neighbor’s new car, your best friend’s new clothes – all of the things you encounter in life are intentionally delivered to you.

Propagandists orchestrate marketing, media, and consumerism. They intentionally control the market and the public’s wants. What started as a way to spread ideas during World War I – religious, political, and social – has become a successful and fundamental marketing tool for society today.