The Paris student revolt of May 1968 was the spark that lit a national conflagration, forcing change on a calcified authoritarian regime.

◊

It started so small – a handful of demonstrators at a university in the suburbs of Paris. Yet it became a cultural turning point, a social revolution that produced the largest general strike ever in France and destabilized the government of French President Charles de Gaulle. Its effects reverberate to this day.

Perhaps the time was just right. By 1968, students all over the world were ready to assert their power, their unified voice, and their opinions about – no, demands for – a more just and equitable world.

That the nexus was in Paris may have come as a surprise to some, including college-age Americans, who thought their anti-Vietnam War protests represented the most important issue of the day. But young Parisians were ready to make their voice heard, and in doing so they threw a rock with an impact felt around the world.

And it all started with sex.

For more on the profound societal and sexual transformations of the 1960s, check out Sex Revolutions on MagellanTV.

Charles de Gaulle and French Postwar Society

It’s often said that the French taught the world how to love. But, in France, the generation that came of age in the late 1960s would beg to differ. French society under General Charles de Gaulle, who assumed the role of President in 1958, was stultifyingly conformist and almost medievally traditional. The free-wheeling image of France’s cupidity was largely an invention of American GIs who visited the country during and post-WWII, and of U.S. intellectuals and artists who took up residence on Paris’s Left Bank between the two world wars.

By 1960, uniformity and responsibility reigned supreme. Nowhere was this more clear than in the French educational system. De Gaulle took pride in the fact that students throughout the country were compelled to study the same subjects, in the same order, at the same time every day. This was de Gaulle’s authoritarian idea of a “free” society and a way to guard against nonconformism, which he believed could lead to unrest or even civil war.

By the late 1960s, France’s “Le Baby-Boom” generation had reached college, and there was a rapid rise in enrollment as they started attending university in France. Demand was so high that a new school was opened in the suburban community of Nanterre, on the northwest fringe of Paris, in 1964. Despite being new, it quickly became well-known as a dreary campus lacking in student amenities. Yet, students who were unable to get into Paris’s most prestigious university, the Sorbonne, filled the classrooms within its first year.

Daniel Cohn-Bendit and the Right to ‘Amour’

It was to this Nanterre campus that one student – a German resident born in France in 1945 – came to study, having received a German repatriation scholarship. Daniel Cohn-Bendit, 20 when he enrolled at Nanterre in 1966, was the son of a German Jewish family that had fled to France in 1933 to escape antisemitic discrimination and imprisonment. Cohn-Bendit returned to the country of his birth to study sociology. He had been imbued with a leaning toward activism by family history – his father had been a left-wing lawyer in Weimar Germany representing members of Secours rouge (Red Relief), an international organization of Communist “revolutionary solidarity.”

Activist Daniel Cohn-Bendit – “Danny the Red” – pushed for a relief in students’ “sexual frustration,” 1968. (Source: FloGalsen, via Wikimedia Commons)

Activist Daniel Cohn-Bendit – “Danny the Red” – pushed for a relief in students’ “sexual frustration,” 1968. (Source: FloGalsen, via Wikimedia Commons)

After the defeat of Nazism, Daniel’s father moved the family back to Germany, where he died in 1958. His son carried his revolutionary fervor with him to Nanterre, but, despite the nickname he would be given, Cohn-Bendit was no communist himself. Cohn-Bendit favored the philosophy of anarchism, one that opposed doctrinaire communism as well as Western capitalism. He soon found an outlet for his activist tendencies, affiliating himself with the campus enragés. These were “angry” activists whose opposition to campus restrictions was filtered through antagonism to de Gaulle’s authoritarian rule of France.

Les enragés were a coterie of perhaps a dozen that sought more freedom on campus. Specifically, they sought to exploit the freedom associated with the recent legalization of the birth control pill, which had come to France only in December 1967. And so, in January 1968, at a ceremony in Nanterre to inaugurate a new swimming pool for students, a group of enragés disrupted the ceremony, with Cohn-Bendit as their loudest voice. He confronted the French Minister of Youth and Sport at the event with catcalls demanding that the university support students’ right to relieve their “sexual frustration” by abolishing parietal rules banning overnight visits in dorms by students of the opposite sex.

The Minister, François Missoffe, was bemused. He wryly suggested that the student leader “jump in the pool” to cool his ardor. Undeterred, Cohn-Bendit escalated the situation when he compared the Minister to the leader of the Nazi’s Hitler Youth. Shocked and surprised, Missoffe was quickly escorted off campus, and the students gained a new campus hero.

Daniel Cohn-Bendit Leads Students as ‘Danny the Red’

Naturally, the university was not pleased by this embarrassing incident. Soon after, the school outlawed any student political meetings. In response, Cohn-Bendit and his dozen enragés occupied the school administration building’s faculty lounge on March 22, while a group of approximately 300 students rallied outside to express their support. The insiders, who became known as the “March 22 Movement,” demanded not only students’ sexual rights but the freedom to gather for political purposes, expressing solidarity with U.S. students protesting “Yankee imperialism” and the Vietnam War.

This got the enragés into more trouble, while gaining them more student support. The doyen (or dean) of the university shut down the school entirely to avoid more student unrest and attempted to expel the 12 occupiers by scheduling a disciplinary hearing on May 3 at the Sorbonne, in Paris’s Latin Quarter.

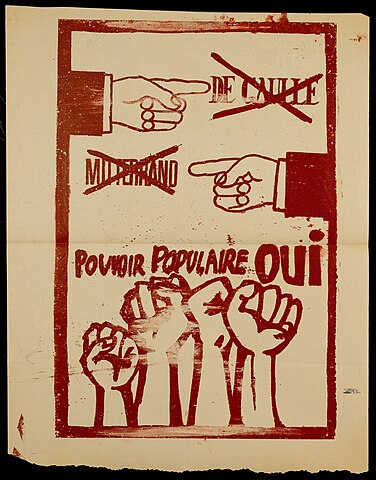

Protest poster from Paris, May 1968 (Source: Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, via Wikimedia Commons)

Cohn-Bendit was a revolutionary celebrity by this point, with a new street name, “Danny the Red,” both for his hair color and his politics. On May 2, he took his growing protest movement to the Sorbonne, where hundreds of students gathered to support Dany le Rouge and his crew. This horrified the rector of the Sorbonne, who overreacted to the unprecedented circumstance by shutting down the school and calling the police to clear the area of protestors.

The Police Nationale, which was responsible for law enforcement in Paris and tended to lean to the far right of the political spectrum, took the request to smash the disturbance literally. They called on their riot squad, the CRS, to descend on the Latin Quarter with armored vehicles, billy clubs, and tear gas, beating students and passers-by indiscriminately and arresting approximately 300.

May 10, 1968: The ‘Night of the Barricades’

The police violence inflamed the students and much of the public as well. Cohn-Bendit called for another march and rally on May 10, and this time the demands had grown far beyond student sexual rights. Their original call for dorm visitation rights faded in prominence. Students now insisted that their schools be reopened, that arrested students be immediately released, and that the police presence in the Latin Quarter be withdrawn.

On the 10th, there were 40,000 protesters on the streets. As the police moved in, the students resisted, prying paving stones from the cobbled streets to throw at the armed CRS officers opposing them. Students built barriers out of school chairs and desks to slow down the riot squad’s attack and overturned cars to block the streets.

The assault lasted well into the early hours of May 11, and became known as the “Night of the Barricades.” Hundreds of individuals had to be hospitalized after police beatings, and 500 students were arrested and charged with rioting. French television and radio, though government-controlled, carried sights and sounds of the protest, and sympathy rose among the public. Protests then engulfed the entirety of France.

Students nationwide went on strike and faced off against the police. They felt emboldened, and their demands escalated again. Now they were calling for the demolition of the French government structure and that power be given, in the socialist model, to “worker councils.” For their part, trade unionists, factory workers, and other members of the French working class walked off their jobs as a sympathy protest. At its height in mid-May, 11 million workers were on strike.

Student protests in Bordeaux, France, in May 1968, resulted in student barricades blocking the streets. (Source: Tangopaso, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

De Gaulle, who had earlier compared the student protesters to “bed soilers” (la chienlit), grew concerned at last, and even left France for a day. At first, some thought de Gaulle had capitulated, but, in fact, he left only to consult with one of his generals about potentially deploying the military to quell the unrest.

The Revolution Dissipates, but Change Is Won

By then, the tides were shifting. Danny the Red left Paris for the much calmer shores of the South of France on May 10. His role as an agitator had been more than successful, and he felt his role in striking the match of the fiery revolt was complete. In any event, on May 24, the government of France deported him back to Germany, and prohibited him, as a “seditious alien,” from re-entering the country.

De Gaulle had the backing of the military and the country’s right-wing “Gaullists,” and on May 24, he gave a televised speech declaring victory over the forces of anarchy. On May 30, over 300,000 Gaullists demonstrated in favor of the government with a march down Paris’s famed Champs-Élysées. By May 30, the students were dispersing as well. With their figurehead gone and the school year at its end, most left Paris for the summer. And when de Gaulle dissolved the government and called for new elections, the Gaullists won a large majority of more than 60 percent of the seats in parliament.

The Aftermath of May 1968: A Social Revolution, Not a Political One

It was 1981 before French Socialists gained control of the French government, with François Mitterrand elected president. Danny the Red became Danny the Green – an ecological activist and member of the Green Party, he was elected as a German to the European Parliament.

What did the students achieve? Were boys finally allowed to sleep over in their girlfriends’ dorm rooms? The answer to that question is perhaps lost to history. It may be that the original sexual rights demand became irrelevant. The revolution did succeed, but not in political terms. It was a social revolution, a revolution in consciousness, and it had enduring consequences.

Students – young people as a generation, Le Baby-Boomers – gained a voice. There was a rapid change in style, from somber suits and ties to the outré fashions that youth in other Western countries, specifically the United States, were wearing. The cultural revolution that hit Britain and the U.S. in 1963 and ’64, with the arrival of the Beatles, finally gained a foothold in France. The ambiance of freedom and sexual insouciance that France exported to America was finally experienced by its own youth.

This upending of societal norms meant that, finally, France’s society had entered the Sixties. And French youth, especially those engaged in progressive causes, realized that, while social change is incremental and challenged at every step, a change in consciousness can be quite rapid, packed into one intense and unforgettable month: May 1968.

To learn more about the workers’ strikes that paralyzed France in May 1968, have a look at The French National Workers’ Strike of May 1968 on MagellanTV.

Ω

Kevin J. Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. Having had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist, he writes on various topics, many in the areas of Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (forthcoming from City Lights). He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: spyrakot, via Adobe Stock