Enjoying a midday meal called “lunch” is commonplace today, but it wasn't always.

◊

We humans are creatures of habit, and eating three meals a day is one of the routines that defines everyday life. On the days when I only eat one or two meals, I tell myself I “skipped a meal,” implying I missed something that was supposed to be there. But, to many of our ancestors, this three-meals-a-day routine would be unpalatable.

Spanning anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour, lunch is a treasured time for people to eat, chat, and do something other than work for a short period of the day. Modern lunch for adult workers might entail reheating leftovers in Tupperware, buying a prepackaged salad from a convenience store, or having a high-stakes business meeting over a meal. Lunch hasn’t been around all that long, but the idea of not having it is unfathomable to many of us.

Learn about the National School Lunch Program in this MagellanTV documentary.

Life Before Lunch

There was a time when people prioritized getting enough to eat rather than cultivating flavors timed with a midday routine. Homo sapiens evolved 300,000 years ago as hunter-gatherers. Survival mandated eating, so humans did what they had to do to follow food, kill or collect it, and prepare it to be edible. Hunter-gatherers found food and brought it back to their tribes, and there are still tribes that do this today. For example, research on the Hadza (or Hadzabe) tribe reveals that while the main objective of a hunt is to return with enough food for one big meal, snacking isn’t all that unusual, even when people are on a mission.

The first agricultural revolution, about 12,000 years ago, saw a pivot from human beings pursuing their food to cultivating it. Being able to grow their own food gave people the chance to time when they ate based on the harvest.

In the morning at a Hadzabe tribe village (Credit: Masele Czeus25, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the morning at a Hadzabe tribe village (Credit: Masele Czeus25, via Wikimedia Commons)

Around that time, the cultural value of “dining” was just getting started. Festivals and celebrations of plentiful harvests were popping up, affording social value to eating. Humans secured food more easily, but a successful harvest in the fall did not ensure there would be enough food for the coming winter, let alone to have several meals a day.

The Thought behind Eating

As societies evolved, so did our relationship with food. Ancient Greeks tended to abide by a “physiocratic school of thought” that highlighted the influence of natural, social, and behavioral factors in a person’s overall health. The ways that the Greeks thought about food and holistic health influenced ancient Romans, who incorporated teachings from philosophers like Pythagoras, Herodicus, and, of course, Aristotle, who emphasized the importance of exercise and finding a balance of “humors” within the human body. While still centuries from understanding the chemical role of certain foods, these philosophers aptly emphasized the importance of moderation when considering one’s overall health.

Keeping in line with philosophers’ praise of the moral virtue of moderation, ancient Romans created a culture around eating only one meal a day. For the wealthy, eating once a day was a sign of moral fortitude. For the less fortunate, however, having a meal even once a day seemed like a success in the midst of famines, plagues, and widespread poverty. This sentiment continued through the medieval period. People in positions of power within the Church were looked up to in Western Europe. They typically embodied a monastic lifestyle emphasizing privation to get spiritually closer to God.

The Meals Sandwiched around Lunch

In medieval times, eating a meal before Mass was looked down upon, no matter how hungry you might have been. Back then, breakfast was prescribed by doctors for sick and elderly patients needing immediate care. If you did eat breakfast, you probably wouldn’t have wanted anyone to know.

As the Middle Ages came to an end, a breakfast of bread and butter along with some ale became a dietary institution in England. Being quite a lackluster meal, breakfast still flew mostly under the radar, even while fueling the Industrial Revolution.

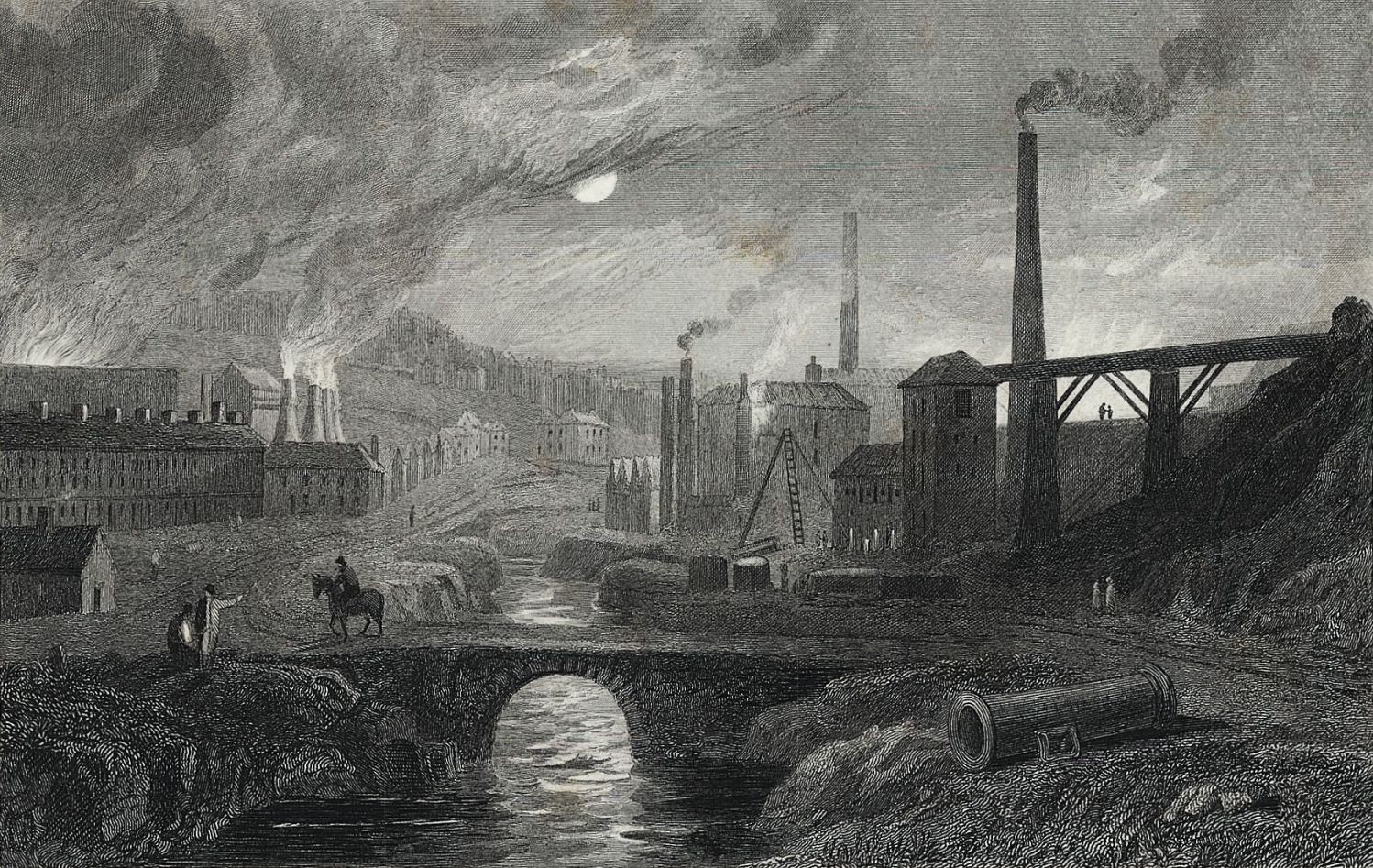

Nant y Glo, Monmouthshire. An industrial scene showing ironworks. (Credit: Henry G. Gastineau and Samuel Lacey, National Library of Wales, via Wikimedia Commons)

Nant y Glo, Monmouthshire. An industrial scene showing ironworks. (Credit: Henry G. Gastineau and Samuel Lacey, National Library of Wales, via Wikimedia Commons)

By the 18th century, a formalized two-meal dining routine became common across Western cultures. While breakfast was still in its infancy, dinner and supper led the way as formalized meals. Dinner was the main meal of the day, eaten around when we have lunch today; and supper was a light repast later in the day. The reason we moved on from a once-a-day dining plan to allocating multiple times a day to eat was due to changing work habits.

As more and more work was expected from the average person to keep up with an industrializing society, productivity was praised over piety – if that meant eating breakfast, so be it. Men, women, and children needed energy to work 12 or more hours in grim, poorly ventilated factories, which took a terrible toll. Not only were people spending most of their lives working, but the majority of the money they earned went toward food. The average factory worker spent 40% of their income on bread alone.

Lunch Makes Its Landing

The work days got longer and longer, so to keep their heads and spirits up, people would take a short pause from work in the afternoon to replenish their energy. They used the word “nuncheon” to describe a light afternoon snack taken in the midst of their workday. The usual nuncheon consisted of bread, cheese, and beer. Sometimes, people would refer to their nuncheon as “lumps.” After a morning ale and afternoon beer, folks tended to slur the words together into the hybrid “luncheon.” We have since dropped the -eon and now use the etymologically odd word “lunch” almost every day.

Luncheon on the Grass, by Édouard Manet (Source: Collection of Musée d’Orsay, via Wikimedia Commons)

Luncheon on the Grass, by Édouard Manet (Source: Collection of Musée d’Orsay, via Wikimedia Commons)

Nowadays, employers typically provide their workers with a lunch break daily. Whether paid or not, the general expectation is that employees will have at least some time to themselves during their workday. How exactly they use that time is usually up to them, but factors like where they work, their income, and their health goals can influence what exact form their lunch will take.

Lunch Staples across the Globe

While habits around food seeped into historical and literary records as a part of a wider cultural dialogue, there are not meticulous logs of what time of day people ate. Thus, there are inevitable gaps in charting the history of lunch.

For the most part, lunch has evolved out of traditions and customs in which people pass along certain recipes, abide by common religious rites, and follow the schedules that people around them tend to stick to. Food is a universal element of the human experience, but the variety of vegetables, meats, grains, spices, and sauces that different people consume means there are an infinite number of forms that lunch can take.

Lunchtime atop a Skyscraper (Credit: Charles Clyde Ebbets, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lunchtime atop a Skyscraper (Credit: Charles Clyde Ebbets, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sandwich

The ingredients that make up a sandwich have been around for millennia, but the iconic food earned its name in the 18th century thanks to John Montagu, the fourth earl of Sandwich. One version of the story goes that Montagu asked his staff to bring him sliced meat and bread so he could eat with one hand and work with the other. Montagu’s one-time request turned into a lifelong affinity for the combination, and, after he began ordering the sandwich at high society events, the food caught on. Today, almost half of all adults in the U.S. polish off at least one sandwich per day. Half of those are eaten as lunch.

Soup

You’d probably have to travel back to prehistoric times to discover the origins of soup. In fact, some archaeologists think pottery dating back almost 20,000 years might be evidence that humans’ ancestors boiled foods in caves that long ago. Canned soup became popular in the 1800s, and John Dorrance’s condensed soup formula helped make this dish increasingly affordable. Andy Warhol immortalized the iconography of Campbell’s condensed soup after having it for lunch every day for 20 years.

Bento Box

People in Japan have transported balls of dried rice in a bag that could be taken on-the-go since the 12th century. Bento boxes, with a small variety of small dishes to enjoy, came into fashion during the Edo Period as a travel accessory. In the 20th century, diners made use of small aluminum tins to store their lunches, and today plastic bento boxes are seen all around Asia and beyond.

Bento lunch box (Credit: HirokazuTouwaku, via Pixabay)

Bento lunch box (Credit: HirokazuTouwaku, via Pixabay)

Tiffin Boxes

These two- or three-tiered cylindrical tin containers feature several unique spaces stacked on top of each other. In Mumbai, India, a fleet of 5,000 dabbawalas on foot, bike, and train deliver hot meals to office workers. They’ve been doing it for 125 years, often picking up the boxes from customers’ own homes and dropping them off at their places of business. The tins usually contain lunches of rice, dal, and a vegetable.

Smørrebrød

The invention of the Scandinavian smørrebrød is similar to that of the sandwich. Often defined as “an open-faced sandwich,” smørrebrød is made of a piece of rye bread topped with butter and some combination of fish, meat, or eggs. Rather than mashing ingredients with a top piece of bread, smørrebrød lets the flavorful ingredients seep into the base layer. Smørrebrød became a go-to lunch in Nordic countries when people started commuting to work and bringing their midday meal with them.

Tacos

Like many idiosyncratic dishes, the exact origin story of the taco is a little hazy. However, some academics believe that the taco got its start in silver mines in the 18th century when miners would bring the portable dish with them to eat midday. The meat wrapped in a tortilla looked similar to some of the explosives wrapped in paper the miners would work with every day. Those explosives were called “taco,” so the name caught on for lunchtime food.

Dissecting Our Diets

Humanity’s need for food needs no explanation, but the history of when we started associating certain meals with certain times is a little more open to study and conjecture. It’s possible that some group of people was dining on three meals a day centuries before. In any case, today we have settled on this frequency of eating as the most beneficial for humans’ holistic health. Or, at least, that’s what most nutritionists seem to think.

Do We Know Too Much?

Between memorable symbols like the food pyramid and the simplicity of having “three square meals a day,” scientists and doctors have tried to make it easy to pick foods to eat and suggest the frequency at which to eat them. Because of advances in the science of nutrition, we have a deeper understanding now about the impact of both what we eat and how often we eat it.

For example, Wilbur Olin Atwater adapted the measure of thermal energy into nutritional energy, giving people a better idea of how much energy a person needs to survive. Atwater introduced the ‘nutritional calorie’ into the average person’s lexicon. This fundamentally deepened humanity’s understanding of our reliance on food, but it opened up some doors for disordered eating as well.

The prevalence of eating disorders has more than doubled worldwide in the last 20 years, particularly among children and adolescents. Some people abide by restrictive diets to regain control of their weight or to increase their overall health. While eating less and exercising is the doctor-approved solution to losing weight, some are opting to try extreme diets that defy the cultural standard of “three square meals a day.”

New Challenges We Face

Recently the OMAD (One Meal A Day) diet has made a comeback, encouraging fasting for the majority of the day. Some people prefer to keep their weight loss diet simply by planning to skip a meal, maybe breakfast or lunch. While on paper this is a straightforward way to lower how many calories you eat in a day, suddenly going long stretches without eating can upset your metabolism. Plus, it doesn’t really address the way fat cells work. Body chemistry aside, the three-meals-a-day mentality is a social and cultural aspect of life that has sunk deep roots in modern societies.

(Credit: Spencer Davis, via Unsplash)

(Credit: Spencer Davis, via Unsplash)

Eating habits in peaceful, economically prosperous nations in the West have taken on a very new form in recent decades. Breakfast and lunch were once begrudgingly eaten to supply just enough to get through the workday. Now, we have to reel in our appetites to avoid overindulging at mealtimes. There’s no denying that the average person’s relationship to food today is a far cry from what it was just a few centuries ago.

For generations now, having lunch has been more than just a meal – it’s a way of life. Whether you see it as a break, a meal, an escape, or an obligation, there’s no denying lunch is a defining feature of modern life. Bon appetit!

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. Originally from Georgia, she now works in Chicago as a tour guide and freelance writer focused on history, small businesses, and marketing strategies.

Title Image: Adobe Stock