Who were the Knights Templar? Go beyond the myths that surround the organization to discover the truth about these medieval “warrior-monks.” Were they a secretive sect, or were they true believers?

◊

If you know of the Knights Templar from their appearances in such films as The Da Vinci Code (2006) or National Treasure (2004), you know their myth, but not their reality. Over many centuries since the medieval era in which they lived, legends have sprung up about the Knights. Like so many contemporary conspiracy theories, these are primarily centered around the belief that they were (or are!) a secret, international organization that held arcane knowledge and possessed wealth beyond belief.

In National Treasure, for example, the Knights were portrayed as direct precursors of another secretive organization – Freemasons – and had managed to collect, over time, priceless treasures and artifacts. Moreover, they had managed to transport them to North America prior to the founding of the United States!

In The Da Vinci Code (spoiler alert!), the Knights even managed to safeguard the dramatic, though fictional, revelation that Jesus of Nazareth had sired a family with Mary Magdalene, whom the Knights were said to revere as saintly.

Over the years, stories about the Knights included the fanciful supposition that they had located and possessed such Christian relics as the Holy Grail, the Shroud of Turin, and even the Ark of the Covenant.

Let’s unravel the myths of the Knights Templar, discuss their real-life adventures, and chronicle their sad and violent end. Because, over about two centuries, these “warrior-monks” created a history, and a legacy, that was not at all secret. In fact, this history deserves to be remembered, even mourned.

For more on the Knights Templar, check out the MagellanTV series Ancient Warriors.

The Temple Mount, and the Causes of the First Crusade

The holiest site in Jerusalem was – and is – the Temple Mount, where the Old Testament states that King Solomon constructed a since-demolished temple to commemorate where David, Solomon’s father, was visited by a divine presence. Revered as holy by Jews, Christians, and Muslims, it was a popular site of pilgrimage, particularly by Roman Catholics, beginning in the Middle Ages.

At this site, where no trace of the original Temple has ever been found, Muslims constructed the al-Aqsa Mosque in the 8th century CE. Muslims made no secret of their enmity toward the Catholics who claimed the Temple Mount as their own. And the Roman Catholic Church was incensed that pilgrims on the trail of Jesus’s steps were being ambushed by marauding Muslim highwaymen.

By the 11th century, sentiment grew in the West that something needed to be done. But what? The Church, powerful as it was, did not have a military arm. And so, in 1095, Pope Urban II called for Roman Catholics, including secular knights from European nations, to lay holy siege to Jerusalem and secure it for safe passage again. This was the dawning of the First Crusade.

Knights from Western Europe descended on surprised Muslims and were able to wrest control of the city by 1099. However, lands surrounding Jerusalem were still in Muslim hands, and attacks on those making pilgrimages continued. In 1119, a French knight, Hugues de Payens, proposed to the pope that a protective order of Catholic knights be formed to serve as guides for pilgrims, assuring them safe passage. The pope agreed and established a small group of nine knights to take up residence in Jerusalem.

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem. In the center of the site lies the al-Aqsa Mosque. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

These knights negotiated with King Baldwin II of Jerusalem to establish a headquarters, and they founded a base in a section of the al-Aqsa Mosque, which the knights, and other Catholics, erroneously believed was the Temple of Solomon. Wishing they’d discovered the biblical Temple didn’t make it so.

The Beginnings of the Knights Templar, the Church’s Military

In 1139, Pope Innocent II issued a papal bull, or public decree, that declared the Knights Templar a favored charitable organization, exempt from taxes, and charged not only with the protection of pilgrims but also with defending Jerusalem and other areas by aggressively fighting Muslim forces.

And so, a military wing of the Catholic Church was established. For approximately 50 years, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, as the Knights were officially known, protected Jerusalem and its religious visitors from attack. But in 1187, Muslims, under the new leadership of Saladin, a military strategist from Tikrit in modern-day Iraq, and the shah of both Egypt and Syria, retook the Holy Land. This led to a massacre of many Knights Templar and the rapid departure of those remaining from Jerusalem and the al-Aqsa Mosque.

Battle of Hattin in 1187, the turning point leading to the Third Crusade. From a copy of the Passages d’outremer, c. 1490. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Regaining the Holy Land became a matter of pride and international unity among Roman Catholic nations, and, in 1189, the monarchs of France, England, and Rome called for another Crusade. The reconstituted Knights, receiving financial and moral support from kings as well as the Church, led the way into battle, acting as the fearless front guard of the attacking troops. They were successful, but over time – and some inspired negotiating with Saladin’s troops – Jerusalem and other prime strategic areas, including the important port of Acre, returned to Muslim control by 1291. Catholic pilgrims were eventually granted safe passage into Muslim lands.

The Beginning of the End of the Knights Templar

In 1303, the Knights finally gave up their favored location in the al-Aqsa Mosque and returned to Europe, with the largest share resettling in France. And here’s where things started getting sticky for the Knights. Over the many years that they were an ascendant force, they grew in power, wealth, and numbers. Even though they had all taken a vow of poverty, or perhaps because of it, they were entrusted with holding the amassed wealth of the thousands of pilgrims during their passage from Europe to the Middle East.

The Knights established a rudimentary “bank,” in which pilgrims “deposited” all their wealth with the Knights at the point of their departure. Using a “bank check,” or letter of credit, they were allowed to collect that wealth, in currency, at their point of arrival. The Knights took a small share for their expenses. Over time, the wealth grew enough that they became a “lending bank” as well, allowing them to finance ventures undertaken by noblemen and even kings.

The financial activities of the Knights Templar constituted the first private bank in the Western world; as it was internationally based, it prefigured today’s international banking system.

One such king was Philip IV of France, who was undertaking a war with England and needed funding beyond his own holdings. The Knights lent him the money that allowed him to wage the Anglo-French War, which lasted for nine years beginning in 1294. But when it came time for him to repay his loans, he balked. Philip felt the Templars had gotten too big for their chain-mail britches, and he resented their amassed wealth. He saw them as usurpers of power that, he reasoned, rightly belonged to kings.

Representation of a Knight Templar displayed at the Ten Duinen Abbey museum. (Source: JoJan, via Wikimedia)

When the Knights rejected a final request from Philip to continue funding the war, the French king launched a plan – a conspiracy – to rob the Knights of their power and transfer their wealth to him. But he needed confederates.

Pope Clement V Enters an Unholy Alliance with King Philip IV

Philip IV believed ardently in the divine right of kings, even when he was up to no good. He had manipulated the election of the pope in 1305 and got his childhood friend Raymond Bertrand de Got selected by a preponderance of cardinals allied with the French monarch. De Got assumed the papal name of Clement V and was indebted to his fast friend Philip forever. He was even instrumental in moving the site of the Holy See (the pope’s residence and base of power) from Rome to Avignon in France, a questionable decision that nonetheless lasted for the better part of a century.

Philip had Pope Clement’s ear, and rapidly used it to his own advantage. While the Knights Templar was a very public organization, it was essentially a religious order and, as such, had certain rituals that were hidden from the lay public. The main covert ritual was the ceremony by which a Knight was accepted into the order and took the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

King Philip had heard specious tales of unbridled excess during these rites from a former Knight, and he was determined to use these purported facts to achieve his goal of destroying them and usurping their wealth. He embellished the tales into outrageously trumped-up charges of heresy and taboo behavior. He accused the Knights of:

- Sodomy and obscene kissing

- Devil worship

- Heresy (performing roles granted only to priests)

- Idolatry

- Denial of Christ, including spitting on the Holy Cross

In addition, he accused them of financial fraud and corruption based on their handling of large sums of money.

Philip was successful in influencing Clement to accept these wild tales, and one of Clement’s first missions as pope was to reign in the Knights and gain control of their finances. In 1305, he summoned the Knights’ Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, to Avignon to discuss merging the Templars with another order, the Knights Hospitaller – and, not incidentally, sharing their wealth with the Church. De Molay resisted, which further infuriated Philip upon hearing the news. As a result of de Molay’s intransigence, Clement willingly endorsed a criminal investigation instigated by Philip against the Knights.

Blood Libel: The Violent Dissolution of the Knights Templar

In good faith, knowing the accusations to be false, de Molay requested that Philip put the charges to rest. But Philip was of no mind to do so. Instead, on October 13, 1307, Philip, invoking his “divine right” as king, ordered all Knights Templar in France – including de Molay – to be arrested and charged as “enemies of the faith.”

So began a period of great duress for the Knights in France. They were tortured into making incriminating confessions, admitting they had done all the things of which they were accused, including worshiping a demon known as Baphomet. This caused a great scandal in France, and the Knights became subject to punishment by the state. They were excommunicated, condemned to life imprisonment, and a significant number were burned alive at the stake, even though their “confessions” were not credible.

One month after the arrests and torture began, Clement issued a papal bull ordering Roman Catholic monarchs in Europe to arrest all Templars in their nations and seize their assets. This was exactly what Philip of France desired, yet his dream of receiving all their wealth as a gift from his childhood friend did not materialize. Instead, Clement paid off Philip with enough money to retire his debts, and split the rest between the Church and Clement’s favored charity, the Knights Hospitaller.

King Philip IV of France attends a burning of Knights Templar. (Credit: Painting by Giovanni Boccaccio, 1480, collection of the British Library, Public domain)

Not all Roman Catholic monarchs participated in the scourge against the Knights. Portugal’s King Denis I, for one, protected the Knights in his country and renamed them the Order of Christ to save them from further prosecution.

The Order of Christ exists to this day, primarily as a government-sponsored secular order, having become an honorary organization in 1917.

However, most nations complied with Clement’s order, and the Knights Templar came to an abrupt end. Their property was seized, and their activities were immediately suspended. Even Jacques de Molay, the Grand Master, was led to the stake in 1314 for a public immolation. From the stake, as the flames began to consume him, he cursed both Philip and Clement, predicting early deaths for them both. Oddly enough, both men died within a year of de Molay’s execution.

The Legacy of the Knights Templar

Did the Knights Templar survive surreptitiously? Did they maintain a secret treasure? Did they possess esoteric knowledge that’s been passed down through the ages? Do they operate in stealth and covertly control the world and its major institutions?

In a word, no.

Though there are organizations today that revere the legacy of the Knights, such as the Freemasons, there are no connections that link current-day associations back to the 14th century. The Freemasons were founded during the Age of Enlightenment in the early 18th century with respect for the Templars but with no direct connection to them.

Every part of the Knights’ legacy, including their bloody and brutal ending, is preserved, in a virtual sense alone, by people and organizations that revere what they accomplished during their active years. All the rest is myth and fiction. But their spirit is undeniably alive in many philanthropic and religious organizations, and many people aspire to their standing as men of faith active in the world. Their legacy is summed up best by one of their sponsors, the abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote these words:

[A Knight Templar] is truly a fearless knight and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armor of faith just as his body is protected by armor of steel. He is thus doubly armed and need fear neither demons nor men.

If only the Knights could have been equally protected from the evil machinations of the Church, working in concert with the Kings of the realm. Their story might have had a much different ending.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on various topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

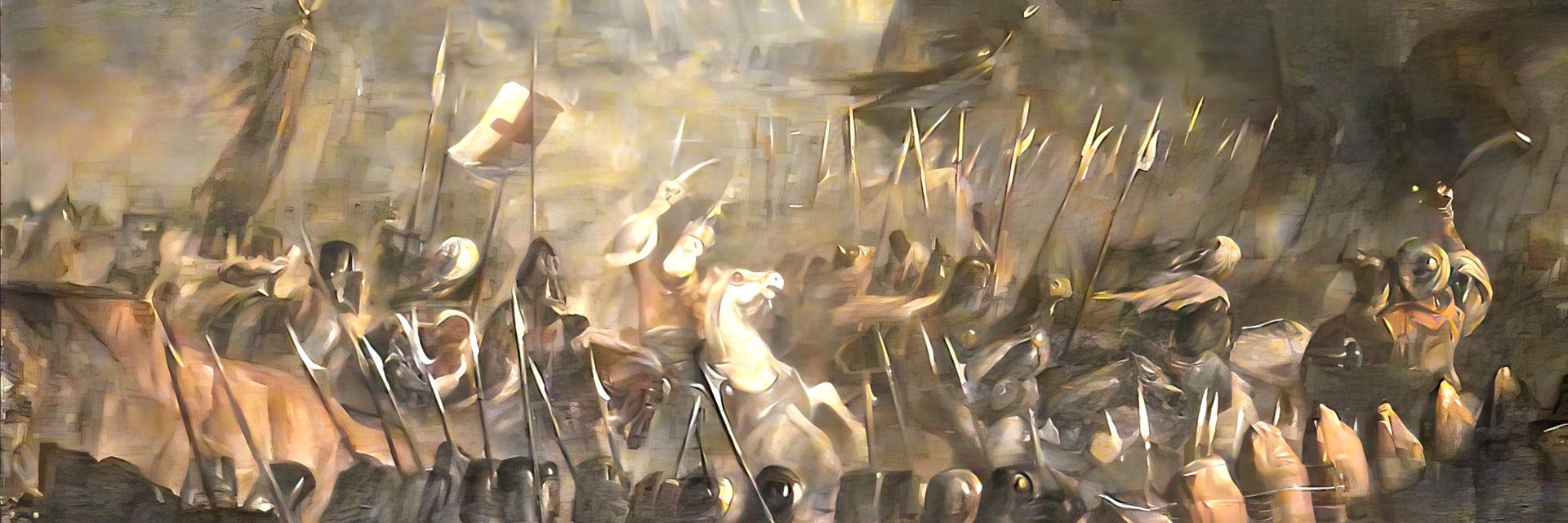

Title Image: Members of the Knights Templar are burned at the stake on order of the French Government. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)