WWI veterans went to Washington during the Depression to lobby Congress for immediate payment of their war bonuses. It ended with a U.S. military assault against them.

◊

The capstone year of the Roaring 20s, 1929, started out so flush, there was actually serious talk that poverty could be eliminated in America. Herbert Hoover, elected in a landslide, took the presidential oath of office on March 4. He promised that his theory of “American individualism” would lead to expanding good times for everyone, even the fabled “Forgotten Men” whom he spoke about so frequently – “rugged individuals” who were self-sufficient and knew how to get along without reliance on government handouts.

One exception to Hoover’s philosophy had been drafted into law five years earlier. This law, the Adjusted Compensation Act, promised that every soldier who served in the Great War of 1914–18 (now called World War I) would be eligible for a cash bonus, a payout for every day they had served, whether in the U.S. or abroad. The bill, passed by Congress over then-president Calvin Coolidge’s veto, had one catch: Veterans would have to wait 20 years, until 1945, for the bonus certificates to mature. Of course, the vets grumbled; they called it the “Tombstone Bonus” for the seemingly interminable length of time they’d have to wait to be able to cash out.

Times were so good in 1929, though, there was an attempt to provide early payment of the bonuses. Democratic U.S. Representative Wright Patman of Texas introduced a bill seeking to allow World War I veterans to receive their bonuses early, rather than waiting until 1945. Vets were disappointed that Patman’s bill, opposed by Hoover, went nowhere, but this grumbling was easy to ignore. Employment was high, stock speculators were getting rich, and the economy was hot.

What a difference a single year made.

Delve more deeply into Hoover’s role in the onset of the Great Depression in this eye-opening documentary.

The Great Depression Crushes Dreams, but One Dreamer Rises Up

In October 1929, the U.S. stock market crashed, signaling the beginning of the Great Depression. The crisis took a torturous toll on those afflicted during the 1930s, and none but the very wealthy could catch a break. Millions across the country lost their incomes, their savings, and their hope for the future. Desperation rose as the stock market slid ever lower. By 1932, 25 percent of the nation’s households had an unemployed head of household.

Hoover, for his part, was seen as intransigent and heartless for his callous refusal even to consider direct government assistance to individuals. Despite his well-earned reputation as a humanitarian when he headed the Commission for Relief in Belgium and the U.S. Food Administration during World War I, as president, he seemed incapable of seeing charity as anything other than the voluntary activity of philanthropists and non-governmental organizations. In his view, it was beyond the role of government to get into the business of providing aid. Many saw his reluctance as evidence that America’s “forgotten men” were indeed being forgotten, this time by their own government.

Amid this spreading economic devastation, one man had an idea. A laid-off cannery worker in Portland, Oregon, Walter W. Waters, decided the time was right for veterans of the Great War to demand that the government pay up on their war bonuses, and now. Many vets had nothing else left of value at that time to pawn or barter but their own goodwill. And goodwill only went so far if you were homeless and had a hungry family to feed.

Waters thought it would be grand if an organized contingent of war veterans descended on Washington to lobby Congress and petition President Hoover to allow them to cash in their bonus certificates. The maximum payout of $625 (for those who had served overseas) would go a long way to relieving the financial desperation so many of them were feeling. In that era, you could purchase a car for that amount!

At first, only a handful of true believers from Portland stuck with Waters as he spread his idea through community meetings. But eventually, he gathered a group of 400 men who had nothing else to lose and were willing to make the cross-country trek to Washington. He called his group the Bonus Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.), a play on the “American Expeditionary Force,” under which they had been organized in France, and set about working through the logistics of such a journey.

The men were willing to take to the rails to get to the District of Columbia, but they couldn’t afford the fare for a berth, or even a seat, on a train. So, instead, they planned to band together and hop freight trains for the week-long adventure.

But it turned out that illegally hopping a freight, with all its risks, wasn’t necessary. Railroad workers, many of whom were veterans, encouraged them. And then, rail authorities stepped in and loaned them a freight train for free. And so, on May 17, a packed train departed Portland carrying the hopes and dreams of approximately 400 war vets, many settled into livestock cars. Spirits were high as they set off on their trek to Washington.

Radio and newspapers carried their story, and the news spread like wildfire. Who could resist such a tale? As the B.E.F. made their way across the mountains and plains of the West, more vets, inspired by their quest, joined their ranks and vowed to get to Washington or bust.

Unfortunately, the initial group’s luck seemed to run out in Iowa on May 18. That was the end of the line for that particular railway. But they didn’t give up. They set out on the roads and highways, hitching rides from friendly motorists who had heard of them and their goal. Many traveled on buses, even on broken-down jalopies with up to 20 veterans hanging off the sides. Some vets hopped freight trains from closer to their destination. The Washington Star reported, “One hundred unemployed World War veterans will leave Philadelphia tomorrow morning on freight trains for Washington.”

Bonus Army vets heading for Washington on the outside of a freight train (Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Bonus Army Arrives in Washington

In Washington, their numbers quickly swelled. Approximately 10,000 vets, many carting their families along with them, reached the nation’s capital in early May of 1932. Luck seemed to be with them. Many respected the veterans’ service to the country and were in league with their quest. A former assistant postmaster general, John H. Bartlett, let the veterans camp on a site he owned called the Anacostia Flats, so named for its proximity to the Anacostia River in the southeastern part of the city. Other vets sought refuge in the shadow of the U.S. Capitol Dome, along Pennsylvania Avenue, occupying abandoned shops and buildings in the depressed city.

Waters, the nominal head of this burgeoning group, established order in the camps. Provisional walkways were set up to organize the vets’ shanties. Waters also had the men create a working sewage disposal system by devoting space to dug-out latrines.

The superintendent of the Washington, D.C., police force, Brigadier General Pelham D. Glassford, a vet himself, also looked kindly upon the men. Although they could easily have been rounded up and jailed as vagrants, the police chief held back his men, allowing the “Bonus Army,” as they were informally called, to go about their business.

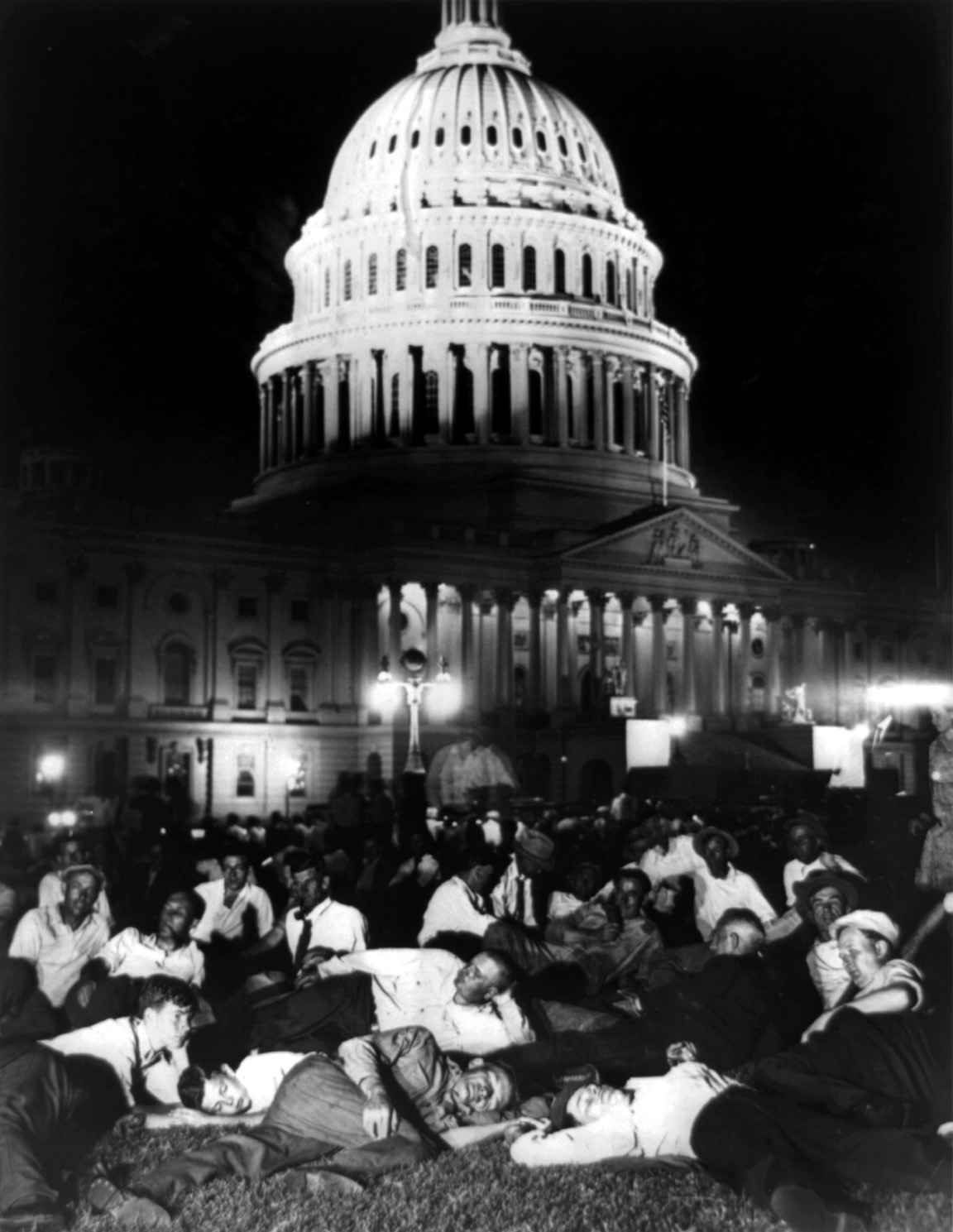

At first, it seemed that the B.E.F. was making progress. Congressman Wright Patman revived his bill to allow war vets to cash in their bonus certificates. As the Bonus Army swelled in May from 10,000 to, by some reports, 20,000 vets, families, and associates, they organized a vigil at the Capitol while the bill was being discussed.

Bonus Army veterans and allies camp out at the U.S. Capitol, June 1932. (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bonus Army veterans and allies camp out at the U.S. Capitol, June 1932. (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

Good feelings ran high when the House successfully passed the bill on June 15. All that was left was to gain a veto-proof majority in the Senate vote. But most senators were aligned with the Republican president, and the bill failed miserably there, dying by a vote of 62-18 on June 17.

That night, the dejected Bonus Army marched back from the Capitol to the Anacostia Flats. A group estimated to be 10,000 strong held a vigil at the drawbridge across the Anacostia River, at the entrance to their camp. They seemed to be ready for anything, now that – in their eyes – their own government had let them down. But the night was peaceful. The policemen let the marchers stand.

After their defeat in Congress, many of the B.E.F. departed Washington, returning to their homes around the country. But a hard core decided to stay, many having nowhere else to go. Their objectives were unclear. Though they were unarmed (as set out in the rules of the camp), many opponents of the group feared that the remaining several thousand might riot. Some actually believed the B.E.F. was conspiring to bring down the government by force.

Among the opponents happened to be a career military man, Douglas A. MacArthur, who at that time held a cabinet position in the Hoover Administration as the secretary of the Army. MacArthur falsely stated, “This is a Communist conspiracy . . . more dangerous than an effort to secure funds from a nearly depleted federal treasury.”

The U.S. Army Attacks Its Own Veterans

MacArthur was wrong, and he knew it. Bonus Army leader Walter Waters was fiercely anti-Communist, and even MacArthur’s internal reports concluded that 90 percent of the camp’s residents were WWI vets and their families. But that didn’t matter now. By mid-July, the Bonus Army demonstrators remaining in Washington were growing restive, and Washington police were contacted by Hoover’s attorney general, William Mitchell, who demanded that the police restore order in the community.

On the morning of July 28, police, brandishing billy clubs, moved in to clear the area along Pennsylvania Avenue that some remaining members of the B.E.F. occupied. The men protested the action, and some tossed bricks at the police. The police action quickly escalated; shots were fired, and two protesters fell, hit by bullets. They later died.

Bonus Army demonstrators created a mock burial ground mourning the loss of both their fellow WWI vets and the hope of receiving their bonuses in 1932. (Credit: Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bonus Army demonstrators created a mock burial ground mourning the loss of both their fellow WWI vets and the hope of receiving their bonuses in 1932. (Credit: Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

This changed the nature of the action against the Bonus Army. When Hoover heard of the violence, he contacted MacArthur, who was already prepared to go into action. By early afternoon, MacArthur had assembled a military force of 3,500 to take action against a crowd estimated in the thousands. At approximately 4 p.m., the military began to move through Washington. There were 200 cavalry members on horseback leading the way. At first, the crowd of vets cheered the military, thinking that it was a parade in their honor. Then they saw the bayonets.

Behind the cavalry were 400 infantrymen, their rifles bearing fixed bayonets. The infantry wore gas masks, and soon Pennsylvania Avenue was awash in tear gas, bringing back memories of the gas the vets had used against their German enemies during the war. The vets then saw tanks rolling through the city, and they retreated quickly to Anacostia Flats, realizing that their country had decided to attack them with military force. The shanties they’d set up in the encampment were razed by the tanks, then set aflame. Their dreams were dying.

MacArthur Disobeys Presidential Orders, Burns Anacostia Flats to Ash

The president could see the flames from the White House and immediately sent a representative with an urgent message to MacArthur to stand down, not to cross the Anacostia River drawbridge into the Bonus Army camp. MacArthur received the message and chose to ignore it, declaring that the vets’ presence represented a threat to overthrow the U.S. government. His chief military aide, Dwight D. Eisenhower, advised MacArthur to reconsider, but his mind was made up. He ordered George S. Patton, then a major and executive officer of the Third Cavalry, to advance across the bridge and clear the area “without delay.”

Carrying torches, the Army set fire to the structures that had housed the Bonus Army vets. Women and children scrambled to safety; one infant died after inhaling tear gas. Newsreels were there to record the chaotic dispersal and the conflagration; they reported, “This is war.” One newspaper, the Washington Daily News, recounted that the Army was “chasing unarmed men, women, and children with Army tanks. . . . If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America.”

Bonus Army veterans’ camp burned by U.S. Army forces (Source: Library of Congress, via U.S. Senate website)

Shockingly, MacArthur was never reprimanded for his actions that day. Even Eisenhower testified that MacArthur’s actions were justified. But Hoover knew he was sunk. His unpopularity overwhelmed his campaign for re-election that year, and Franklin D. Roosevelt won by a landslide in November.

Hoover Remains One of History’s Most Unpopular Presidents

In 1933, there was a smaller second Bonus Army march on Washington. This time, FDR responded with empathy and intelligence. Though opposed to an early bonus payout, he sent his wife, Eleanor, to the encampment to speak to the vets and their families. Roosevelt himself offered the vets jobs through the Civilian Conservation Corps. Many accepted.

In 1934, over Roosevelt’s veto, Congress finally passed a bill allowing for the immediate redemption of the vets’ bonus certificates. Two billion dollars were paid out. And, despite his veto, Roosevelt was viewed as a winner, offering direct relief to suffering fellow citizens, in stark contrast to Hoover’s recalcitrance and violent assault. Today, Roosevelt is often listed among America’s most popular and effective presidents in history, and Hoover is near the bottom. Though the Bonus Army veterans may have officially been among the U.S.’s “forgotten men,” today they are remembered for burning Hoover’s presidency down to its foundation and helping clear the way for FDR and the New Deal.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. A journalist and communications specialist for many years, he writes on various topics, including Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (City Lights) and resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Bonus Army vets confront the Washington, D.C., police force, July 28, 1932 (Source: Signal Corps, via Wikimedia Commons)