Renoir’s long-standing anti-Semitism affected his career choices and his artistic style. Bigotry and hate negatively impacted an otherwise-beloved artist.

◊

This is a story about art. It is also a story about hatred. Combine the two and what ultimately results is the diminishment of an artist as well as the disfigurement of his legacy.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, whose art we more commonly associate with luscious nudes and languorous, lazy afternoons, was also an anti-Semite. His long-lasting enmity toward Jews colored his aesthetic strategies and his career choices. He both lusted after commissions from the wealthy Jewish elite of Paris, and equally harbored deep resentments toward them that sometimes erupted into ugly diatribes.

Renoir’s Humble Start in Art

Renoir came from humble beginnings. His parents, both tradespeople, migrated from the small town of Limoges in central France to Paris when young Pierre-Auguste was three to seek better prospects for the growing family. Nonetheless, they lived in penury and, when Renoir was only 13, he was forced to leave school and begin an apprenticeship in a ceramics factory. His modest wages helped support his family.

It wasn’t long before his flair for ceramics decoration – an important trade of the time – began to be noticed. With his rising salary and the approval of his family, he was able to take art lessons, which he complemented by spending long hours in the Louvre. He took his study seriously; he began to see himself as a fine art painter, able to advance his standing both in wealth and in society. But he continued working as a ceramics artist to keep his head above water.

Renoir’s early years provided lessons in frugality. He lost his job in ceramics in 1858, when he was 17, as mechanical processes for printing designs on ceramics were introduced. That knocked him back considerably, and he found himself unable to purchase paints without donations from his better-off friends, fellow painters Alfred Sisley and Claude Monet.

Check out Renoir And The Girl With A Blue Ribbon 4K on MagellanTV.

Renoir’s Anti-Semitism Surfaces

Unlike many of his peers, Renoir was financially unable to avoid military conscription by paying another person to take his place in the corps. So, when French ruler Napoleon III declared war on the Prussians in 1870, Renoir was drafted. Though saved from direct combat, his experience nonetheless made him miserable. He was assigned to an equestrian unit in the south of France, a position for which he had neither skill nor training. Making matters worse, he ultimately contracted dysentery, adding to his pain, discomfort, and indignity.

During and following the war, France was seized by a furious reaction to its fate. Many French citizens believed that their esteemed nation, with its history of conquest and domination, could not have lost this war on a level battlefield. Aspersions were cast on likely culprits in the defeat, but one group was singled out for blame: the Jews.

Perhaps the most infamous episode of French anti-Jewish sentiment at the time was the Dreyfus Affair. In 1894, a Jew serving in the French military, Alfred Dreyfus, was accused of espionage for the Germans. Despite faulty, trumped-up evidence, he was convicted – a victory for the right wing and anti-Semites looking for a scapegoat, but an act of gross injustice in the view of liberals and others who did not share the hatred of their Jewish fellow citizens.

Renoir, fresh from the humiliation of his military service, was all too eager to latch on to the lies and fraudulent allegations that typified the anti-Semitic right. His fertile mind picked up on themes that Jews were insufficiently patriotic, even traitorous, and he repeated these ugly tropes, in his studio and elsewhere, for the rest of his life.

But an inconvenient reality for artists – especially early in their careers – is that they are beholden to their patrons. For Renoir, this became peculiarly fraught, as many of those upon whom he depended for financial support were, in fact, Jews. And one in particular was critically important to the next phase in the artist’s development.

Renoir Seeks Entrée into Parisian High Society

Jewish families of high status formed a tight social circle in Paris. They also had similar tastes when it came to collecting art. Advised by a trusted member of the group, a collector and critic named Charles Ephrussi, they concentrated primarily on art of the 18th century, including large-scale academic history and myth paintings by Fragonard and Bouguereau. Some, with trepidation (but with Ephrussi’s imprimatur) stepped gingerly into the realm of contemporary art of the late 19th century. They tended to acquire select works representing both Impressionism and the similarly popular artistic trend of the day, Japonisme.

Renoir, back from the war and in increasing need of gaining commissions to support himself, wanted to gain access to the gatekeepers of these new “amateurs” of art. His potential patrons and collectors both attracted and repelled the anti-Semitic Renoir. Still, he needed an introduction from Ephrussi to members of the critic’s extended family and social circle for the purpose of gaining portrait commissions. To that end, he aggressively stalked Ephrussi and approached him at a public event, entreating the critic to view his paintings, even as he privately disparaged him.

To a degree, Renoir’s strategy worked – Ephrussi was duly impressed by Renoir’s work, and soon the artist was invited to salons juifs to meet potential clients. Renoir allowed Ephrussi to select works from his oeuvre to submit – successfully – to the annual Salon in 1879. This newfound celebrity also opened doors to additional commissioned portraits of members of Paris’s Jewish upper crust.

Renoir Breaks with Ephrussi and His Social Circle

Not all went well for Renoir in his transactions with these patrons. Accustomed as they were to the Neoclassical 18th century works they were fond of collecting, Renoir’s clients were sometimes shocked by Renoir’s mild Impressionist experiments with form and light. An example is his 1880 portrait of Irene Cahen d’Anvers, daughter of a wealthy Jewish family, unofficially titled “Girl with the Blue Ribbon.”

“Portrait of Mademoiselle Irène Cahen d’Anvers” (“Girl with the Blue Ribbon”) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1880 (Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection, Zürich, Switzerland)

Today, the painting is revered as a beloved work of psychological depth that features a mastery of color effects. However, it was dismissed by the girl’s father and hung in a back hallway of the Cahen d’Anvers home. Worse, from Renoir’s vantage, the man of the house insulted the artist by giving him the paltry sum of 1,500 francs (about US $260 in today’s dollars) for the work.

Cahen d’Anvers’s wife, however, did appreciate the work and asked Renoir to paint their two youngest daughters. But the final double portrait was not perceived as successful by either the painter or the patrons. Monsieur Cahen d’Anvers refused to give Renoir even a sou for this work, leaving the artist ready to burst with pique.

Renoir had always derided Ephrussi for being Jewish; now his disparagement pushed into the red zone, and he publicly ended his association with his former friend. He is quoted as saying, “As for the 1,500 francs from the Cahens, I must tell you that I find it hard to swallow. The family is so stingy; I am washing my hands of the Jews.” Of Ephrussi, he maligned, “That man, more Jew than bourgeois, has the right eye for the so-called salon" [de beauté] (beauty salon), punning on the dual meaning of the term salon.

“Alice and Elisabeth Cahen d’Anvers” (“Pink and Blue”) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1881 (São Paulo Museum of Art, São Paulo)

With Newfound Financial Freedom, Renoir Finds Success

Renoir was caught in a bind of his own making, caused primarily by his ingrained anti-Semitism. He no longer wanted to take lucrative commissions from his former Jewish patrons, but he absolutely wished to make paintings that were celebrated and led to profitable sales. And, for once, Renoir had the means to paint “for pleasure.” He embarked on an ambitious work that he hoped would gain him the attention he craved, ideally by exhibition at an Academy-sponsored annual Salon.

The work, “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” accorded Renoir great public acclaim. Exhibited first not at a Salon but at the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition of 1882, the dramatic work exemplified these artists’ motto, “Luxe, calme, et volupté.” The impression of this painting of a group of people crowded in a confined space is one of joie de vivre, or joy of life.

The patrons and staff, modeled from Renoir’s friends and the actual staff at the dockside resort, seem overpowered by the fragrance of a lazy summer’s day. They are doing nothing more than luxuriating in their space and enjoying the calm of a singular moment abstracted from their whole day. The figures are captured with a voluptuousness that reflects the light dappled across both their clothing and skin, as well as the very volume of the figures, who seem to be bursting with life and rosy complexions.

“Luncheon of the Boating Party” by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1881 (The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC)

Renoir could not have been happier with the resulting recognition. The painting was named the best work of the exhibition by numerous writers, and it was purchased from the show by the influential international art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, a friend of Renoir and Monet, who kept it in his private collection for the remainder of his life.

Renoir’s grand success occurred just as he was breaking from Charles Ephrussi. Ephrussi makes an appearance in “Boating Party,” though he appears stiff and turns his back to the partiers. It’s unknown whether Renoir posed him this way out of enmity or spite.

How Renoir’s Pride and Prejudice Caused a Shift in His Artistic Style

Despite the critical acclaim and financial rewards he received for “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” Renoir was in an artistic quandary. He felt his experiences attempting to shoehorn his Impressionist style into clients’ Neoclassical expectations were an aesthetic failure, and for a while this contradiction paralyzed his artistic evolution.

He lamented, “Around 1883 a sort of break occurred in my work. I had gone to the end of impressionism, and I was reaching the conclusion that I didn’t know how either to paint or draw. In a word, I was at a dead end.” With his new wealth, he devised a way through his artist’s block: He would tour great European capitals of art for inspiration, traveling to Rome and Florence to absorb classical Renaissance works by Raphael and Titian.

This was Renoir’s escape from his frustration with his former clients’ rejection of his earlier style. The painter now emphasized the pale pastels of his predecessors’ palette and a newfound drafting skill in creating carefully constructed and modeled figures – especially faces. Because he left so little paint on the surface of his canvases, as opposed to the heavier impasto style with thick application of paint, he called this his “dry” period.

Ironically, Renoir had now moved his work closer to Salon acceptability, and closer to the tastes of the social set he’d broken with. Today, these works, such as “Young Girl Bathing” (1892), are praised for the construction of the figure and profile of the sitter, though his most popular pieces are celebrated for hewing closer to a purely Impressionist style.

“Young Girl Bathing” by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1892 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

As the artist’s star continued to rise, he became inundated with more requests for society portraits, which he accepted, carefully and with discrimination. But his attitude toward potential clients had not evolved along with his art, and he eschewed commissions from Jewish patrons.

Renoir and His Legacy

Renoir’s work passed through many stylistic periods, and in the end, we understand him as a master of light and form. But as we saw, when he changed his art to please his Jewish clients, then broke with that approach for his short-lived “dry style,” he went from one dead end to another.

To be clear, it is not the intention of this article to impugn Renoir’s art itself as anti-Semitic. But as he whip-sawed back and forth from greater to lesser influences of the Impressionist style, the reactionary shift in his aesthetic strategies was ultimately deleterious to his career and its long-term development. Ultimately, anti-Semitism was a cancer that blinded Renoir to its effects, diminishing the man and obscuring the primacy of his art.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

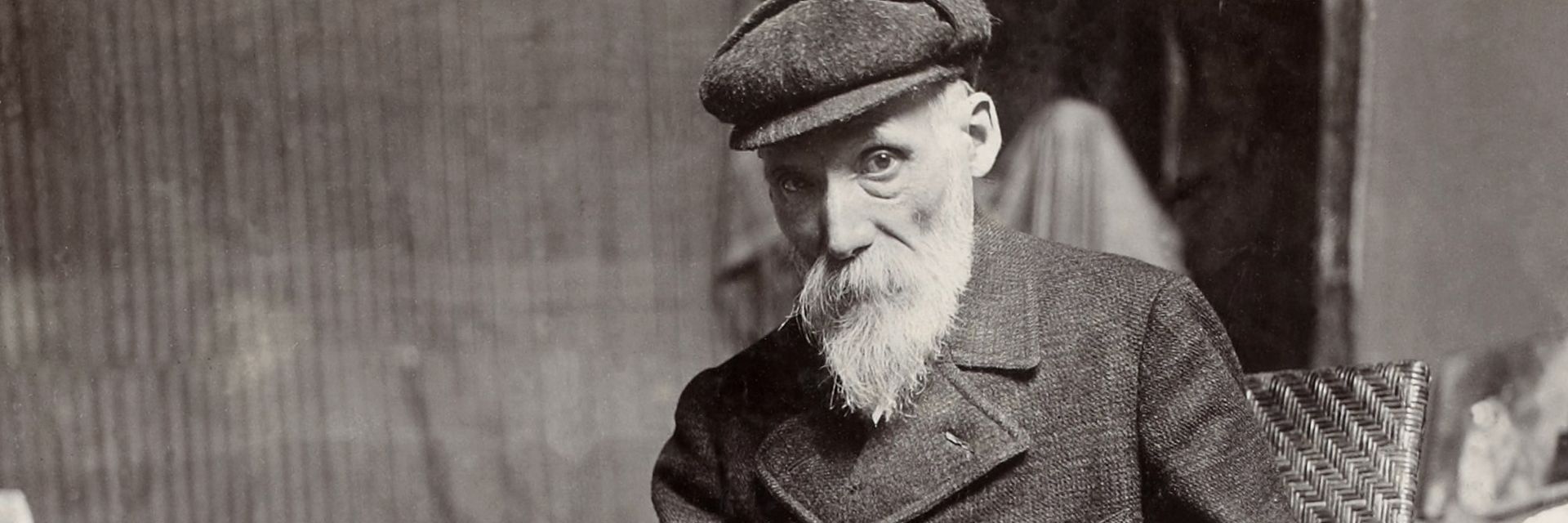

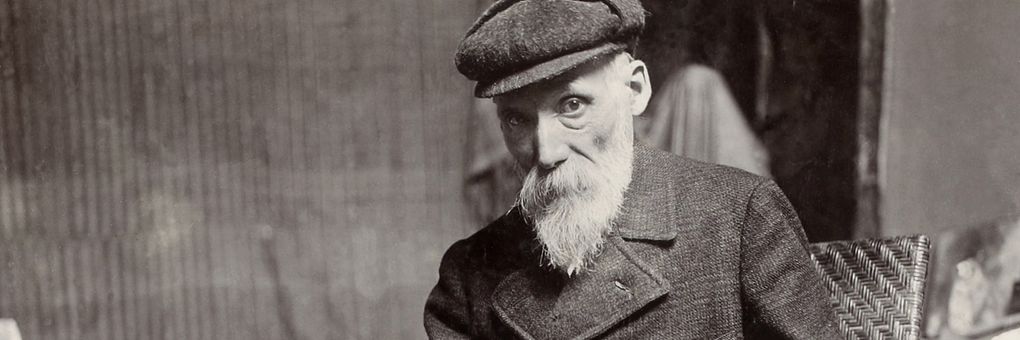

Title Image: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c. 1910) via Wikimedia Commons.