Composer Frédéric Chopin lived in virtual exile from Poland, the beloved country of his birth. But, from his adopted home of Paris, he wrote music that extolled the history of the people of Poland and its nationalistic pride. Today a strong vein of Polish nationalism is again ascendant, but is its contemporary expression truly the same as in Chopin’s day?

◊

November 2018 marked the 100th anniversary of Poland’s independence from Russia, and it was time for the annual parade and rally in Poland’s capital, Warsaw. Who could be against a big parade, with floats and banners and a sea of flags flapping in the wind?

Well, the mayor of Warsaw, for one.

Warsaw’s mayor of the time, Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz, canceled the parade due to her concerns about “aggressive nationalism.” In 2017, the parade had been taken over by far-right nationalists who started fires, burned flares, displayed obscene, anti-immigrant messages, and started fights with bystanders.

The mayor’s cancellation of 2018’s events didn’t last for long. Poland’s decidedly right-wing president, Andrzej Duda, out-maneuvered her and the parade was back on. And, as she’d feared, it was overrun by far-right neo-nationalists and marked by racist banners, burning the EU flag, and scattered skirmishes.

It just wasn’t quite as bad as 2017’s event, so Duda declared it a success.

Contemporary, “aggressive” Polish nationalism is a far cry from the nationalism of the mid-19th century. One of the early proponents of this philosophy was classical composer Frédéric Chopin, whose version of musical nationalism, as we’ll see, carried echoes of the Enlightenment – stances quite different from those of Poland’s nationalistic organizations currently.

Nationalism in Poland emerged in an era when Poland was occupied and oppressed by its Russian overlords. It promoted freedom for citizens and self-determination for the nation, along with other elements of the Enlightenment worldview. And Chopin masterfully incorporated these ideas into his compositions through the use of native Polish folk melodies and traditions.

You would be forgiven for assuming that Chopin would be sympathetic to contemporary nationalism; in fact, he would likely be outraged.

When Romanticism Met the Enlightenment: Chopin’s Liberal Nationalism

Chopin gained fame as a cultural figure in Paris. Though he had been born and raised in Warsaw, his prodigious talent for performing and composing masterful works for piano took him to Europe’s cultural capital to build a career.

He quickly became known for popularizing a style of music rarely, if ever, previously heard in concert halls. Classical music listeners would have recognized that there were themes and motifs that did not derive from the world of “pure music.” Instead they were borrowed from folk tunes and forms native to Eastern Europe, and specifically the land of the composer’s birth, Poland.

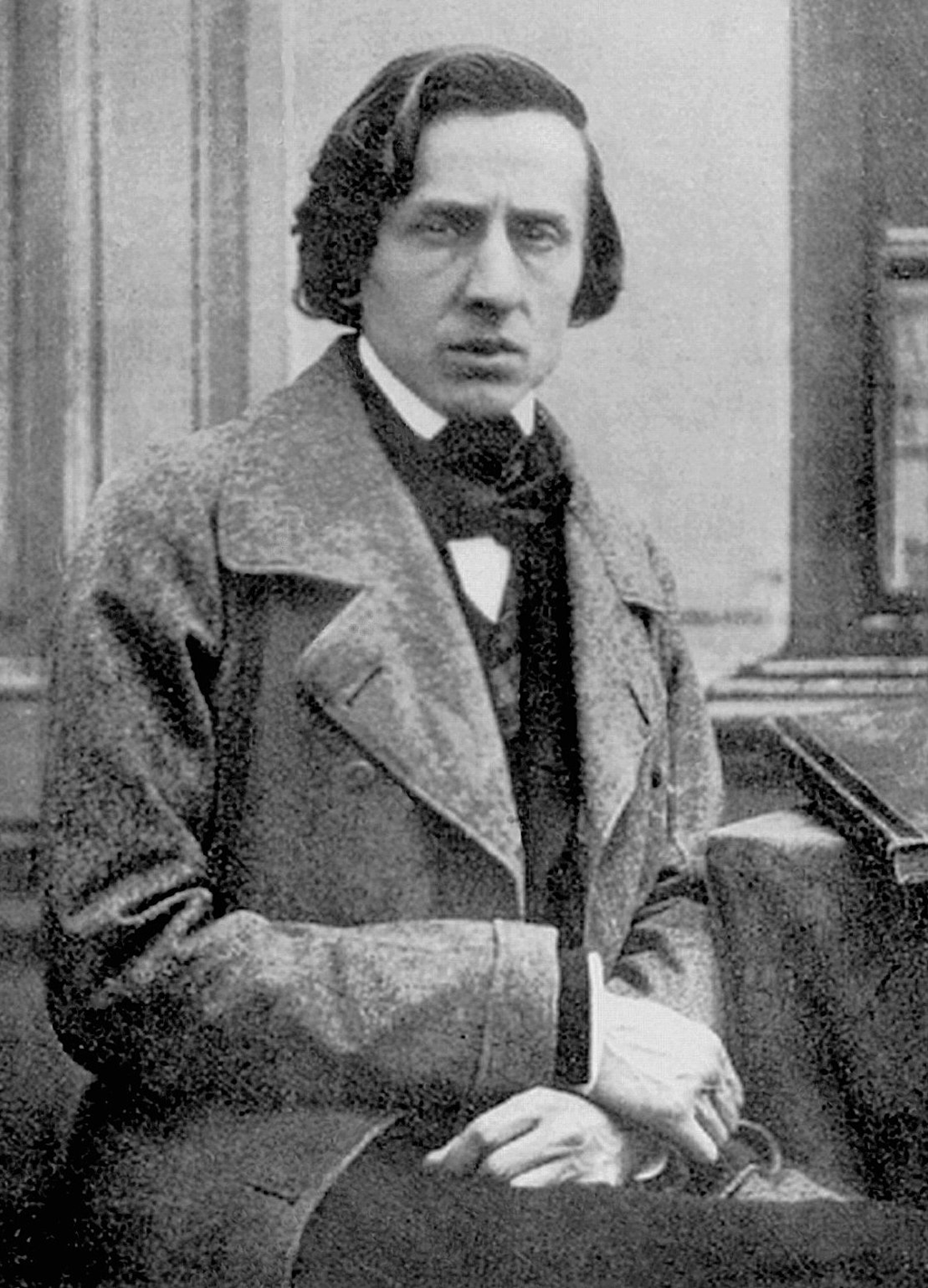

Chopin in 1849

(Image courtesy of Wikimedia)

You see, Chopin had arrived in Paris at age 20, in 1830, and would never reside anywhere else till death – yet his lineage was Polish. And he was proud to incorporate Polish themes into his music, even though the sources came not from the drawing room but from the fields and hills of his homeland’s folk history.

Romantic composer Robert Schumann, an admirer and friend of Chopin, was also a writer. He understood the political message entwined with the beauty of Chopin’s music. Upon hearing Chopin perform his B flat minor Sonata, he characterized the piece’s inherent nationalism as “cannons concealed amid blossoms.”

In Chopin’s time, it would have been unusual to mix “high” (concert hall) idioms with the “low” influences of common folk. Although this practice would later become very popular – think of Ferde Grofé’s Grand Canyon Suite or Aaron Copland’s ballet Rodeo – Chopin was among the first composers to utilize these kinds of popular influences in his concert works.

The Political Rise of Musical Nationalism

The juxtaposition of art songs with folk songs in concert halls carried an electric charge of politics. It was well-known that Poland was a partitioned, occupied nation – and Russia was not the Poles’ first or only overlord. But at that time it was Russia that occupied the nation with a swift, cruel fist. Polish culture and the Polish language were curtailed and even banned.

It was apparent through Chopin’s Polish-themed music that its composer was drawing attention to this injustice, and was calling for the return of Polish sovereignty to the people and their native land. This fusion of art and ideology became known as musical nationalism, as it aligned with the Enlightenment-influenced political nationalism that was part of the contemporary discourse. It was so powerful and enduring that, even during the Nazi occupation of World War II, Germany forbade the playing of his music because of its powerful pro-independence symbolism.

Chopin was sensitive to events in his home country and, in his heart, along with many of his fellow Poles, he desired independence ardently. But peace and freedom were far-off dreams. Despite the many voices of the Enlightenment calling for liberty, equality, and fraternity, and despite the examples of the French and American revolutions, Russia controlled Poland and had no intention to let go.

We think of Chopin as a Pole to his core, but he was actually born in Warsaw into an immigrant family. His father was French and had moved to Warsaw and established a career and a family, marrying a young Polish woman. It was only through Chopin’s growing awareness of his plight and his passionate music-making that he came to be seen as a protector and defender of Polish nationalistic pride.

How Chopin’s Musical Nationalism Was Formed

Chopin was very inventive with his music for piano, creating or refining various forms that revealed the finesse of a talented pianist. And often his forms were drenched with Polish cultural and folk themes. He wrote masterful études, nocturnes, and mazurkas, and above all was known for his polonaises, which were based in folk forms of the Polish people.

Chopin loved his birth nation so much he literally left his heart there. Although he is buried in the well-known Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, he instructed his family to return his stilled heart to Warsaw, where it was interred in a pillar at the Church of the Holy Cross.

To call Chopin’s music nationalistic means that his writing for piano and orchestra is infused with themes and motifs reminiscent of centuries of independent Polish culture. They exemplify cultural nationalism, allied with but quite separate from political nationalism, in their emphasis on the traditional music and sounds of the Polish people.

Polish Nationalism Then and Now – How It Has Changed in the 21st Century

Musical nationalism was founded on liberalism. It also drew from another philosophy of the age, Romanticism, which emphasized individuality and identity as forces to promote over the old ways of thinking. During this period, music and the other arts were powerfully influenced by the ideals of the Enlightenment, as seen in the work of Mozart and Beethoven, among others.

But nationalism evolved. And while it once heralded joy and discovery of a national culture, it’s different now. Way different.

(Image courtesy of Mazaki, via Wikimedia)

Over the generation that has come of age since the Soviet Union’s breakup and the restoration of autonomy to the Polish nation, a new wave of nationalistic fervor has arisen. But rather than following the liberal values that excited Chopin in the mid-19th century, this neo-nationalism is enamored by values festering on the other side of the ideological spectrum.

To make an impression in Poland’s nationalistic circles now, you’d probably want to avoid classical music and instead try rapping. According to Buzzfeed News, rap music is all the rage to express the feelings and explosive emotions of today’s young neo-nationalist radicals.

In 2015, the right-wing party Law and Justice came to power in Poland’s parliamentary elections. Since then, there has been a sharp rise in the visibility and public actions of other, more radical nationalist organizations.

The Rise of Right-Wing Polish Nationalism

You might wonder why nationalism would be on the rise in today’s independent nation of Poland, a full-fledged member of the European Union and NATO. As with other nationalistic movements in contemporary Europe, a major reason could be fear of internationalism, as represented by the EU. Polish neo-conservatives believe their “Polishness” is under attack by the “forces of liberalism” and that, within the current global order, Poland is not fully sovereign.

The right-wing nationalists in the country today promote a vision of a Poland stripped of modernity, without the leavening effects of equality and the common good. In fact, human rights are threatened by their rhetoric, which opposes the presence of foreigners (in particular, refugees), homosexuals, and nonwhite people. Even non-Christians are expunged from this view of a sovereign Polish nation. This extremism is shocking; even more is how widely these ideas have traveled and taken root over the past couple of decades.

In contrast, Chopin had a cosmopolitan view of the world from his perch in urbane Paris. He foresaw a future state of Poland that would embrace its freedom and connection with other, like-minded nations. Profoundly influenced by the Enlightenment and Romanticism, it’s just not possible to imagine Chopin forging a philosophical connection with a neo-nationalist community that stands in adamant opposition to a classically liberal worldview.

Chopin’s music was “cannons concealed in blossoms,” as Schumann so eloquently put it, with its stirring themes evoking a passion for the promise of individual and national freedom. Passion burns at the heart of Polish nationalism today, but it is a fire of exclusion, intolerance, and bigotry. Chopin’s brilliant musical nationalism will not be co-opted by such a perverse and destructive vision for his beloved homeland.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Chopin concert, 1887. (Credit: Aavindraa, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)