“We understand your paranoia / But we don’t want to play your game” – John Lennon, “Bring on the Lucie,” 1973

◊

J. Edgar Hoover had become perpetually hot under the collar. The well-structured American ethos of law and order – and conformity – that he had crafted in his long career as head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation from the 1920s through the early ’60s had begun to disintegrate. What replaced it was a multifaceted psychedelic mandala of radical social experimentation and, worse, drug-taking as the late ’60s metastasized into the leftist political activity and counterculture movements of the early ’70s. And he was having none of it.

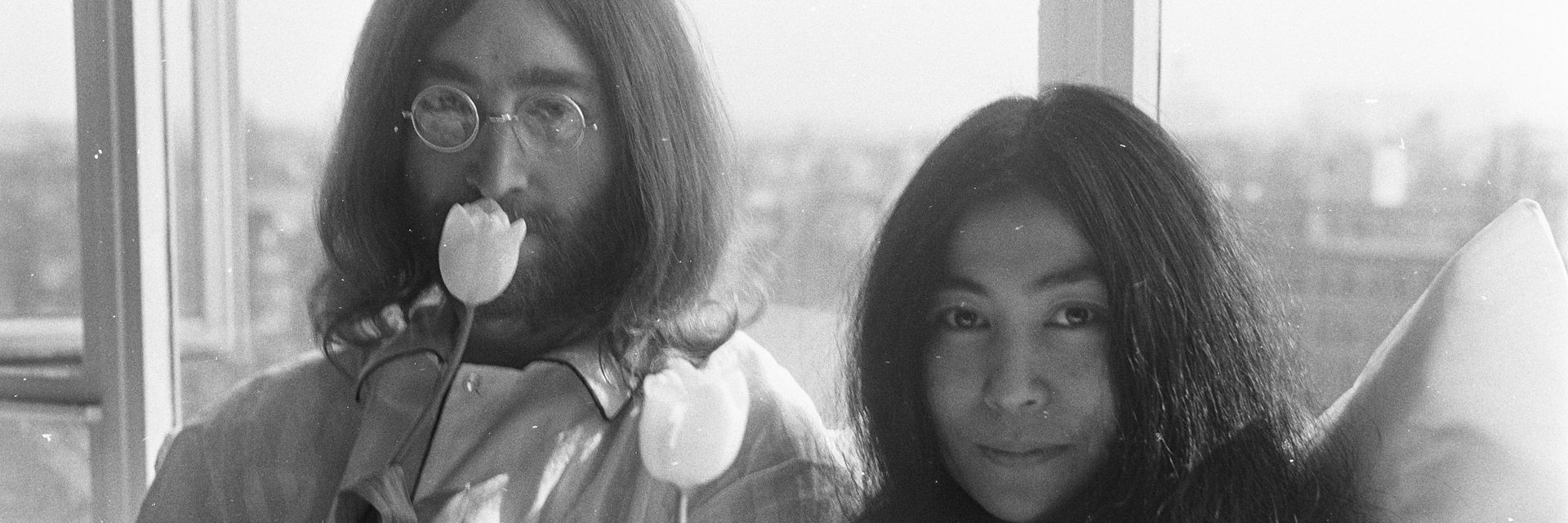

At first, John Lennon wasn’t on Hoover’s radar despite being remarkably active after the breakup of his legendary band, the Beatles. His relationship with and subsequent marriage to Fluxus artist Yoko Ono, and their antics on the world stage, transformed the pair into cultural instigators.

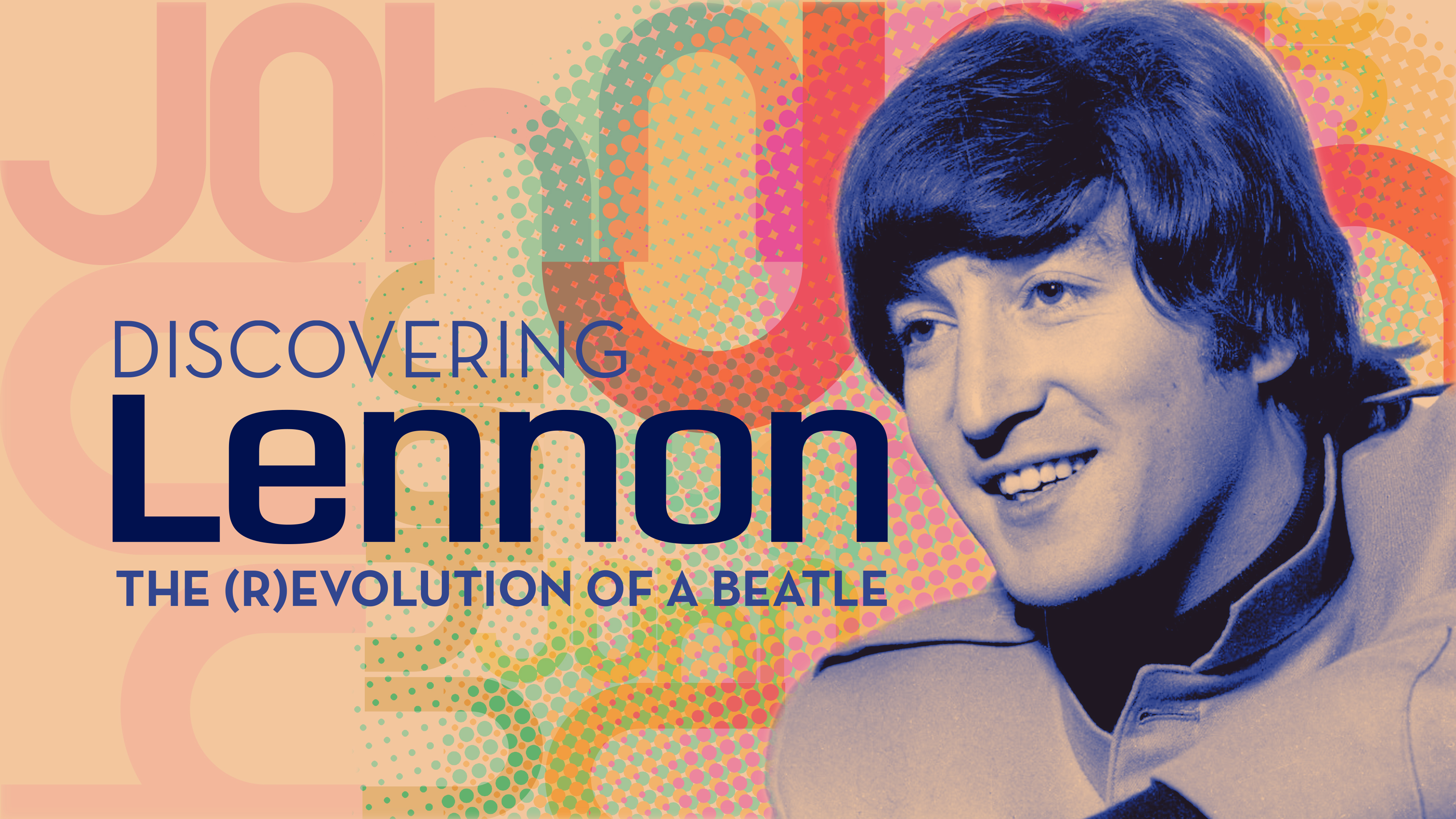

From their infamous nude double portrait on their album Two Virgins to the two “Bed-Ins for Peace” that they performed in Amsterdam and Montreal in 1969, Lennon and Ono were breaking new ground in the worlds of art and celebrity. But they weren’t overtly political then, and, importantly, they weren’t in the U.S. So, if Hoover knew of them at all, he didn’t perceive them as a clear and present danger. Yet.

Explore all facets of John Lennon’s life and career in Discovering Lennon.

Since 1968, Lennon had been prevented from entering the U.S. due to his London arrest for possession of cannabis. But by 1971, he had worked out his visa problems and settled in New York City with his wife and collaborator. That’s when things started to get sticky for Lennon, and he came into sharp focus through the lenses of Richard Nixon’s presidential administration and Hoover’s FBI.

John Lennon: Rebel with a Cause

At the very end of the peace-and-love ’60s, Lennon used the spectacle of the Montreal Bed-In to record the epic-though-ramshackle anthem, “Give Peace a Chance,” with Yoko and a crew of hangers-on. Lennon took the sentiment in that song to heart and sought to put his words into action as a U.S. resident. Soon enough, he had a cause: a case of misapplied justice in the American Midwest.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, “Bed-In for Peace,” Amsterdam, March 1969 (Source: Eric Koch / Anefo, via Wikimedia Commons)

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, “Bed-In for Peace,” Amsterdam, March 1969 (Source: Eric Koch / Anefo, via Wikimedia Commons)

Michigan hippie and left-wing activist John Sinclair was a hero to many for, among other things, promoting marijuana use and founding in 1968 (with the blessing of the Black Panther Party) the “White Panther Party,” an “antiracist political collective” that championed antiwar and anticapitalist causes. In reality, they were generally stoned or tripped-out jesters who were especially good at self-promotion and taking compelling self-portraits that showed them carrying guns and ammo. But they weren’t actually violent; they just liked to be seen that way.

This kind of public attention-seeking naturally put them in the sights of Michigan authorities, and it wasn’t long before Sinclair was set up for a pot bust in 1969 by a pair of undercover police officers. He passed them two joints and was promptly arrested and jailed for possession. His rapid conviction and sentencing to 10 years in prison for this crime got national attention, and many on the left and in the counterculture rose up to decry the obviously political nature of the prosecution.

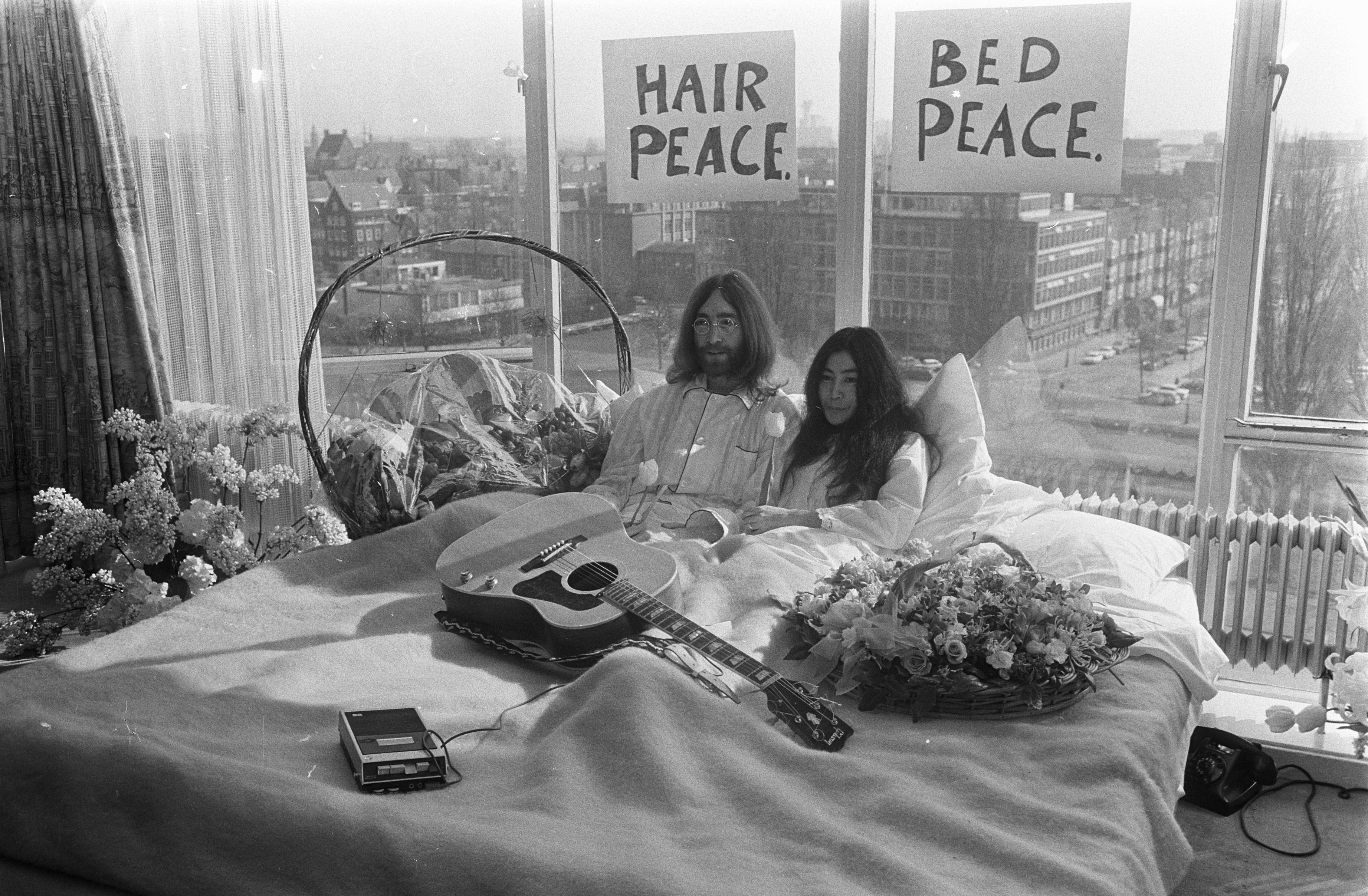

Two years into his imprisonment, in December 1971, activists planned a “John Sinclair Freedom Rally” in Ann Arbor, Michigan. High-profile organizers such as Bobby Seale and Jerry Rubin put their energy into the event, seeking the participation of both musicians and political speakers. Rubin, who was traveling in the same NYC circles as Lennon and Ono, presented the idea to them, and they enthusiastically accepted the offer to perform. Lennon actually wrote a song for the event, “John Sinclair,” with lyrics such as, “They gave him ten for two / What else can the judges do? / They gotta . . . set him free.”

The six-hour concert/teach-in was a rousing success, and the authorities responded quickly. Two days following the event, Sinclair was released from prison. Soon after, Sinclair’s arrest record was entirely expunged.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally, Ann Arbor, Michigan, December 11, 1971 (Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Yoko Ono and John Lennon at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally, Ann Arbor, Michigan, December 11, 1971 (Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Hammer Comes Down on ‘Give Peace a Chance’

Lennon was overjoyed by the results of his efforts and started talking about setting up a nationwide tour of benefit concerts in 1972, the proceeds of which would be donated to prisoners and prison rights groups. Other reports implied that these concerts would be specifically political, designed to motivate youth to vote to remove Richard Nixon from office. Many of these young people would be casting ballots for the first time since the voting age had been lowered to 18 in 1971.

Whether this latter report was fact or rumor, news of it trickled into mainstream sources and caught the attention of the U.S. Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, chaired by Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. Thurmond, who made his name as a racial segregationist and staunch opponent of civil rights legislation, also happened to be a rabid anti-Communist. He was alarmed, fearing (without foundation) that political opposition to Nixon was a Communist plot.

On February 4, 1972, Thurmond wrote a “personal and confidential” letter to John Mitchell, Nixon’s attorney general, stating that the Lennon matter should be “considered at the highest level” of the government. He suggested that action against the singer could avoid “many headaches.” The memo he attached said that Lennon was associating with “New Left leaders” who were “strong advocates of the program to ‘dump Nixon.’”

The New Left represented a broad swath of social justice causes, from opposition to the Vietnam War to civil rights. Influenced by countercultural and anti-establishment ideas and leftist leaders like Tom Hayden and Angela Davis, it was viewed by some as a threat to social order and even national security.

The memo asserted that “a commune” financed by Lennon planned to disrupt the 1972 Republican National Convention, which was scheduled for San Diego that August. It concluded, “If Lennon’s visa is terminated, it would be a strategy counter-measure.” Ten days later, on February 14, Deputy Attorney General Richard G. Kleindienst messaged Immigration Commissioner Raymond F. Farrell, asking if there was any legal basis to have Lennon deported.

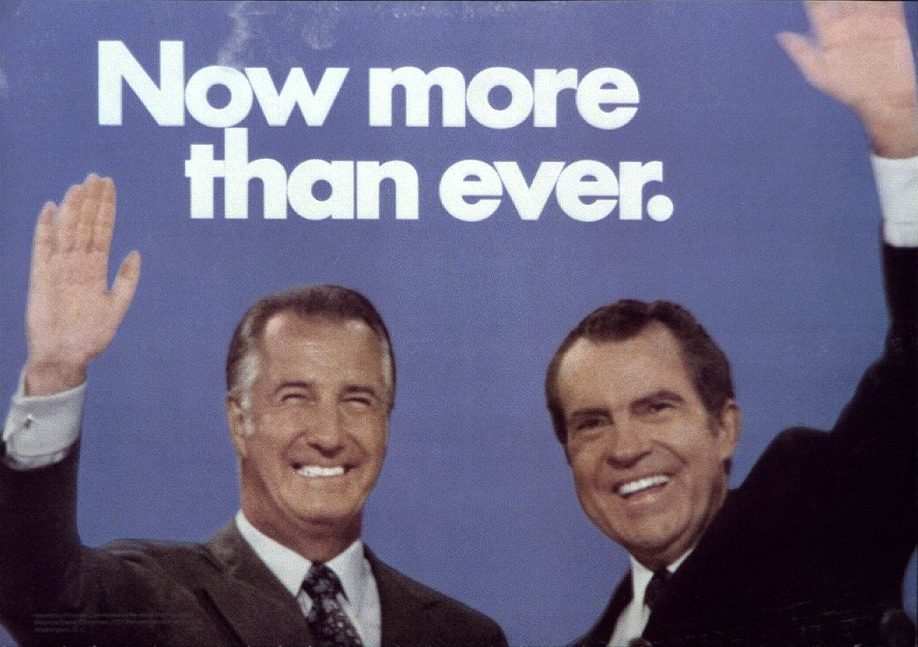

A 1972 campaign poster for Vice President Spiro Agnew (left) and President Richard Nixon, who ran on a conservative “law and order” platform, attacking the left. (Source: Yanker Poster Collection, via Wikimedia Commons)

A 1972 campaign poster for Vice President Spiro Agnew (left) and President Richard Nixon, who ran on a conservative “law and order” platform, attacking the left. (Source: Yanker Poster Collection, via Wikimedia Commons)

On March 2, the New York office of the INS received direction to begin deportation proceedings. Lennon was ordered to leave the U.S. within 60 days. The immediacy of the deportation threat was enough to scuttle any plans he had to embark on a concert tour. Thurmond’s political intimidation campaign, outlined only weeks earlier, appeared to have succeeded.

Hoover’s FBI and the CIA: Gathering Intelligence against Lennon

The FBI soon joined the campaign to “neutralize” Lennon. They had had Lennon under surveillance since 1971, and, in April 1972, Hoover sent a memo to the New York FBI office stating, “Lennon should be arrested, if at all possible, on possession of narcotics charges . . . which would make him immediately deportable.” Surveillance was stepped up, and some reports indicate that his telephone calls were monitored. Lennon was known to go to his next-door neighbor to use a phone that he was reasonably certain wasn’t being bugged.

The memo also said, “In view of the subject’s avowed intention to engage in disruptive activities surrounding the [Republican National Convention], the New York office will be responsible for closely following his activities until time of actual deportation.” (In reality, Lennon told Jerry Rubin that he would only make an appearance at the San Diego convention if it were strictly nonviolent and if his presence was completely unannounced.)

The FBI even sent a poster to New York law enforcement agencies indicating that Lennon was wanted for arrest on drug charges. It included a purported photo of the rock star along with his physical description. Laughably, though, it turned out that the photo on the poster wasn’t of Lennon but another downtown NYC pothead, David Peel.

J. Edgar Hoover was at the heart of all this political subterfuge, and he influenced the CIA in the surveillance effort as well. On April 25, Hoover sent a hand-delivered memo to Nixon’s chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, noting that the musical artist held sympathies with “extreme leftwing activities in Britain.” Hoover died one week later, on May 2, 1972, making this his final crusade.

After all this hoopla and harassment, Hoover’s desire to nab Lennon came to naught. On August 30, 1972, Hoover’s successor, L. Patrick Gray, received a memo from the New York FBI office indicating that Lennon had withdrawn from leftist politics. It stated that Jerry Rubin, another FBI “person of interest,” had ceased contact with Lennon due to his “lack of interest in committing himself to involvement in antiwar and New Left activities.” Lennon’s FBI file was classified as “inactive.”

Lennon Fights Deportation for 3+ Years

The FBI’s failure to have Lennon arrested didn’t stop the INS’s plans to deport him. That fight dragged on for more than three years as Lennon’s lawyer, Leon Wildes, continued to protest and appeal every move by the INS. The lawyer even sued the FBI, alleging that his client was the victim of illegal wiretapping.

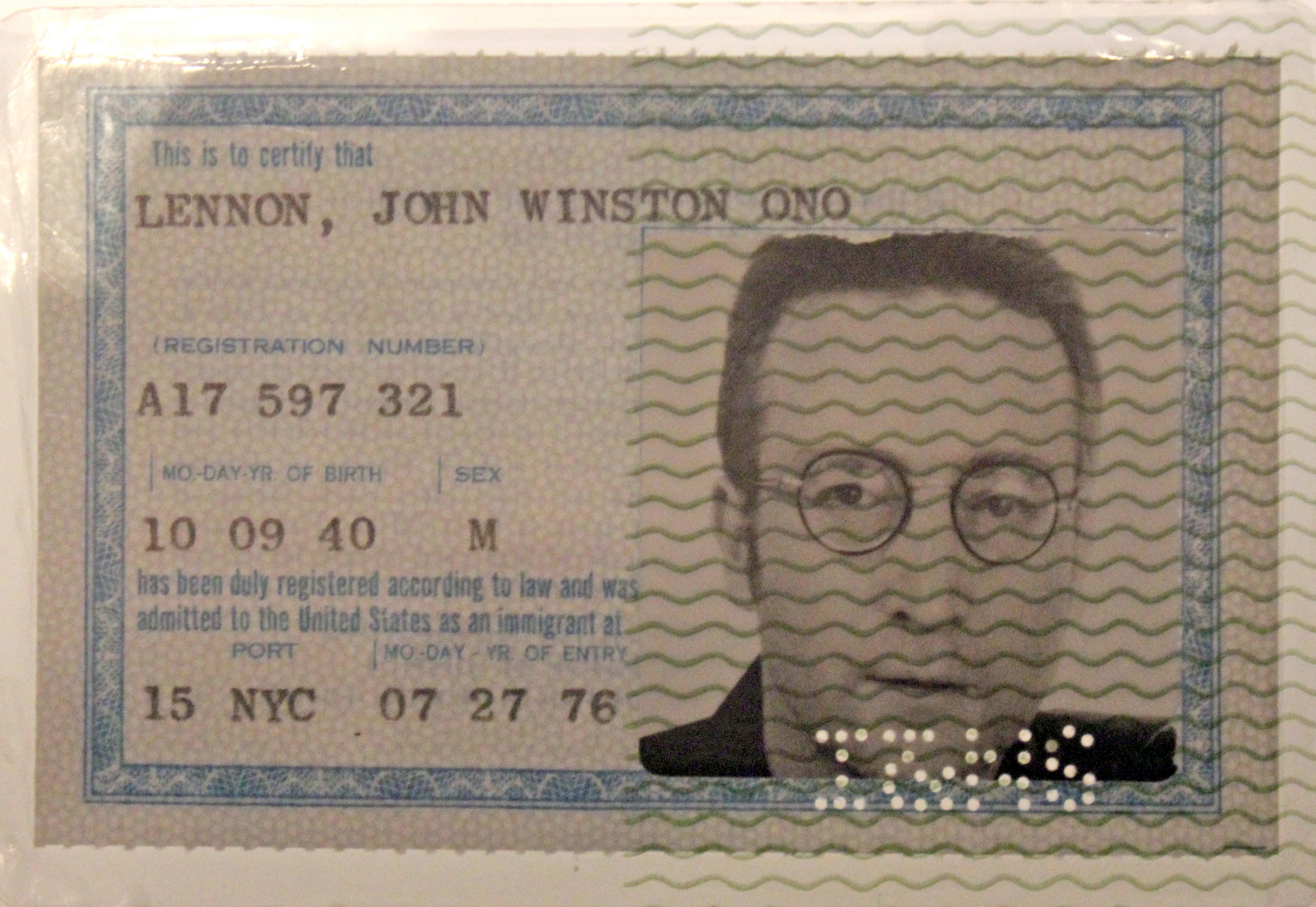

John Lennon’s hard-fought prize, a “green card” guaranteeing U.S. residence without harassment (Source: Rodhullandemu, via Wikimedia Commons)

John Lennon’s hard-fought prize, a “green card” guaranteeing U.S. residence without harassment (Source: Rodhullandemu, via Wikimedia Commons)

Wildes was quoted as saying his client “understood that what was being done to him was wrong. It was an abuse of the law, and he was willing to stand up and try to show it – to shine the big light on it.” Lennon finally won his case against the INS on October 7, 1975, just two days before his 35th birthday. He received his green card and was allowed to maintain his residence in New York unimpeded.

The judge writing the final decision in the case was quite clear about the issues at stake with Lennon’s legal treatment. He said, “The courts will not condone selective deportation based upon secret political grounds. . . . Lennon’s four-year battle to remain in our country is testimony to his faith in this American dream.”

‘Gimme Some Truth’: Lennon Returns to a Private Life

Ultimately, however, all the harassment and litigation took a toll on John Lennon. Wildes was instrumental in persuading the artist to avoid making further political statements that might invite legal backlash. Rapidly, everything about Lennon’s life shifted. It affected his music, which became more personal and less anthemic, as well as his lifestyle with Yoko and his social associations – no more hobnobbing with the Left.

In effect, the government’s coordinated campaign against Lennon was a resounding success. Without being forced into exile, he was silenced or, in official language, neutralized. But what if he had stayed the course, without persecution, touring for social causes and writing politically inspired tunes with iconoclastic lyrics? What kind of social force could he have become?

Just imagine.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. A journalist and communications specialist for many years, he writes on various topics, including Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (City Lights) and resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image (top): John Lennon and Yoko Ono, “Bed-In for Peace,” Amsterdam, March 1969 (Source: Eric Koch / Anefo, via Wikimedia Commons)