No one is ‘normal,’ but we are quick to stigmatize or feel ashamed of mental illness. Why?

◊

A couple of kids found him in the Charles River. They even tried to save him. Poor kids. What a thing to see. Two little boys dropping their fishing rods and wading in to pull the body out. He’d never learned to swim.

“Escaped,” written in perfect cursive on a 5x7 card, was the reason he wasn’t at Medfield State Hospital outside Boston. Suicide was the reason he was no longer living. He’d barely made it to 21 before deciding he’d had enough. Enough of what?

I never met the young man who killed himself. He was my uncle, my mom’s little brother. He died long before I was born. My mom, nine years his senior, had already left Massachusetts for New York with a plan to become an actress when he began having the sort of problems that eventually led to stints at Medfield State.

I also never found out the details. People didn’t talk about those things back then. Maybe they didn’t know how. This was, after all, the generation still reeling from two world wars. Soldiers coming home from World War II, for example, exhibited “battle fatigue,” a term almost as unhelpful as “shell shock,” used for WWI veterans. Maybe they were ashamed. "Maybe" is all I have for my forebears, the taciturn generation originally from Sweden, Russia, and Ukraine whose New England character was hammered into them by hardships.

Originally named Medfield Insane Asylum when it opened in 1892, Medfield State Hospital closed its doors in 2016. By the time I began searching for information about my uncle, records had long since been destroyed by a warehouse fire. My sleuthing would have been stymied regardless, however, since Massachusetts has strict laws governing access to medical records, even those of people dead for more than 50 years. Somehow, though, that 5x7 card remained in a file in Worcester – the card that summed up a young man’s life with “escaped” and “suicide.”

For a heartwarming tale of triumph over mental illness, check out Overcoming Depression: Mind Over Marathon.

Stop Acting Crazy!

No one is normal. Some just have more difficulty functioning than others. My struggles, for example, though debilitating, pale in comparison to my uncle’s misery. Nevertheless, and despite my mother’s almost desperate insistence to the contrary (“Oh, Mia, you don’t have problems!”), my history of emotional distress was all I ever knew, and so it was simply...me. I was in my late 30s before I sought help for the obsessive tendencies, bouts of abject terror over the thought of being around people, and near-hysteria at the certainty of impending doom — all masked by a sort of poker face. These conditions had been lifelong plagues on my consciousness, and so pervasive, they structured my very being. But I can only imagine what life is like for people like my uncle, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia sometime in the 1950s – or for others diagnosed with major mental illnesses.

The disorder we now call schizophrenia was initially identified in the late 1800s as early dementia. In 1911, Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler combined “schizo” and “phreno,” both from the Greek, to reflect the condition of a “split mind.” That term, along with “split personality,” became the commonly misused descriptions of the disorder.

People struggling with mental illness have been through the wringer, and then some. Indeed, the entire enterprise of medical science has gone through intense growing pains. Woe unto the poor wretch in the Middle Ages, for example, whose infection was thought to be an imbalance of the humors. Bloodletting by leeches was the cure. Then there were those whose ulcers were thought to be stress-related before the actual pathogenesis was discovered to be the H. pylori bacteria in 1982. The researchers won a Nobel prize for their discovery.

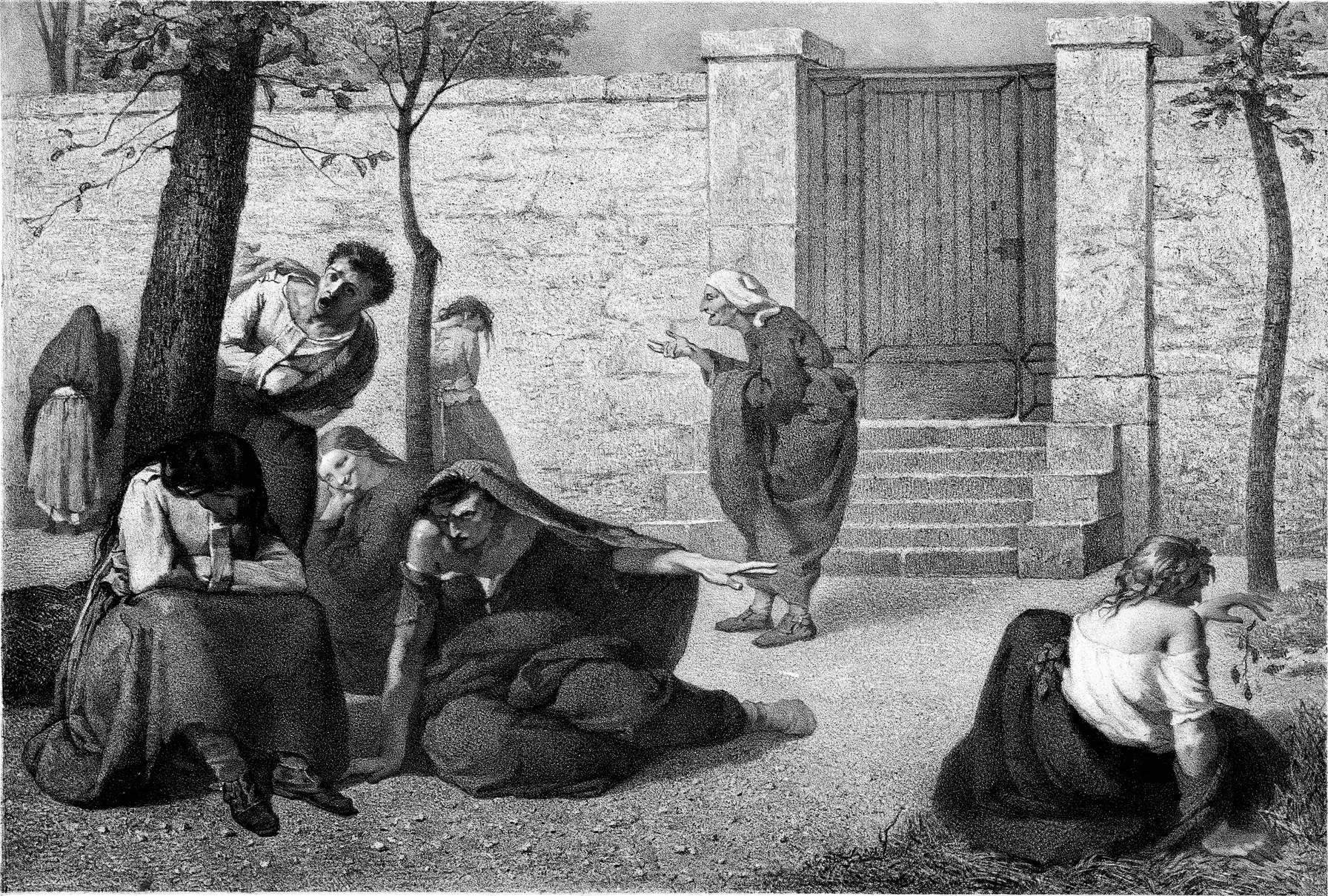

1857 lithograph by Armand Gautier, showing personifications of dementia, megalomania, acute mania, melancholia, idiocy, hallucination, erotomania and paralysis in the gardens of the Hospice de la Salpêtrière.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Ignorance, combined with dogmatism, is a breeding ground for erroneous causal connections, oppression, and violations of autonomy – all of which generate enormous suffering. Some ancient peoples, for example, believed hallucinations were punishments from the gods. The Medieval period saw torture as the appropriate response to those thought to be possessed by demons, while inhumane conditions in asylums are common in some places today.

In his 1961 book, Madness and Civilization, French thinker Michel Foucault argued that the 17th century’s “Great Confinement” – the period in which confinement houses segregated the mentally ill from the rest of society – marked a dramatic turning point in societal attitudes toward the mentally ill.

Freud famously explained emotional problems through an artfully constructed vision of women as inferior to men (not a terribly novel idea, but … really?). Then there’s the fact that homosexuality was listed as a disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as recently as 1973. And last, but far from the least, since the 1950s, one after another pharmaceutical therapy was marketed as the solution to our mental ailments – this despite a lack of conclusive evidence that chemical imbalances cause mental illness. In fact, some recent research suggests depression, for example, is not caused by chemical imbalance, and some psychiatrists argue that they’ve long worked to debunk such causal connections as myths.

OMG, You’re Insane!

All of this assumes there is something that can be objectively described as “normal.” In some ways, this makes perfectly good sense. For example, a healthy body functions in specific ways, while an unhealthy one does not. Disturbances of our physiological equilibrium can generate immense suffering. We want to be well, which is to say, normal or healthy. The person who insists they see or hear a long-dead relative is likely hallucinating, and hallucinations aren’t objectively real. Hence, they’re not normal.

So, it’s helpful that there are medications that work well to alleviate these experiences, particularly given that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to treating the associated conditions. That said, if the individual is not a danger to themselves or others, and life otherwise goes well, should a person who hallucinates about a dead relative be treated? Suppose that person is some sort of artistic genius? (People have long speculated about a connection between exceptional creativity and mental illness.) Now suppose that the artist hallucinates, and that medication would mitigate or stop the hallucinations, but could it also stop that person from creating great works of art?

In Western medicine, most ethical considerations revolve around autonomy and consent. These two concepts, in turn, rely on assumptions about our rationality, namely our ability to make our own choices about our lives free from interference.

Of course, one person’s normal is another’s hellscape. Consider sleep. It’s something everyone needs, regardless of how healthy they are. I have known, envied, and, I admit, resented anyone who thrives on fewer than six hours a night. (I wonder if Warren Zevon, who wrote, “I’ll sleep when I’m dead,” was one of them.) Nevertheless, the Centers for Disease Control have devoted an entire chart, disaggregated by age, to how many hours of sleep are recommended every night for optimal health.

Unfortunately, the stigmas historically associated with mental illness – stigmas that still exist today – are disconnected from our physiology. Instead, they are often rooted in our fears about social acceptance, unpredictability and dangerousness, and idealizations of rationality. First, we’re social creatures. (Even introverts like me want, at some level, to be accepted by our community.) Second, we’re the sort of creatures who seek patterns and demand at least the illusion of predictability. Unexplained events make us nervous – we want to know the causes of things. Third, and related to the first two points, we typically see our rationality as our defining feature.

You’re Totally Irrational!

But what is rationality, such that we can contrast it with the non-rational or the irrational? Plato, for one, proposed that humans are constituted by three elements: the appetites, the passions, and reason. Plato thinks reason should order or control the appetites and passions, since reason alone is capable of knowledge. That rationality is supposed to include our capacity for abstract thought, deliberation, and drawing conclusions.

There is also a long history of thinking about the mind as an entity separate from our bodies. In the 1600s, for example, Descartes argued for the reality of an immaterial substance – the mind – which is a radically different kind of thing from the body. The mind, in Descartes’ view, is that which thinks, and thinking includes reasoning, willing, feeling emotions and sensations, and imagining. Most significantly for Descartes, thinking never occurs without a thinker. So, I am, fundamentally or in essence, a thinking thing. My identity is bound up with the mental. Any disruption of the mental is, then, a disruption to my very existence.

.jpg)

.jpg)

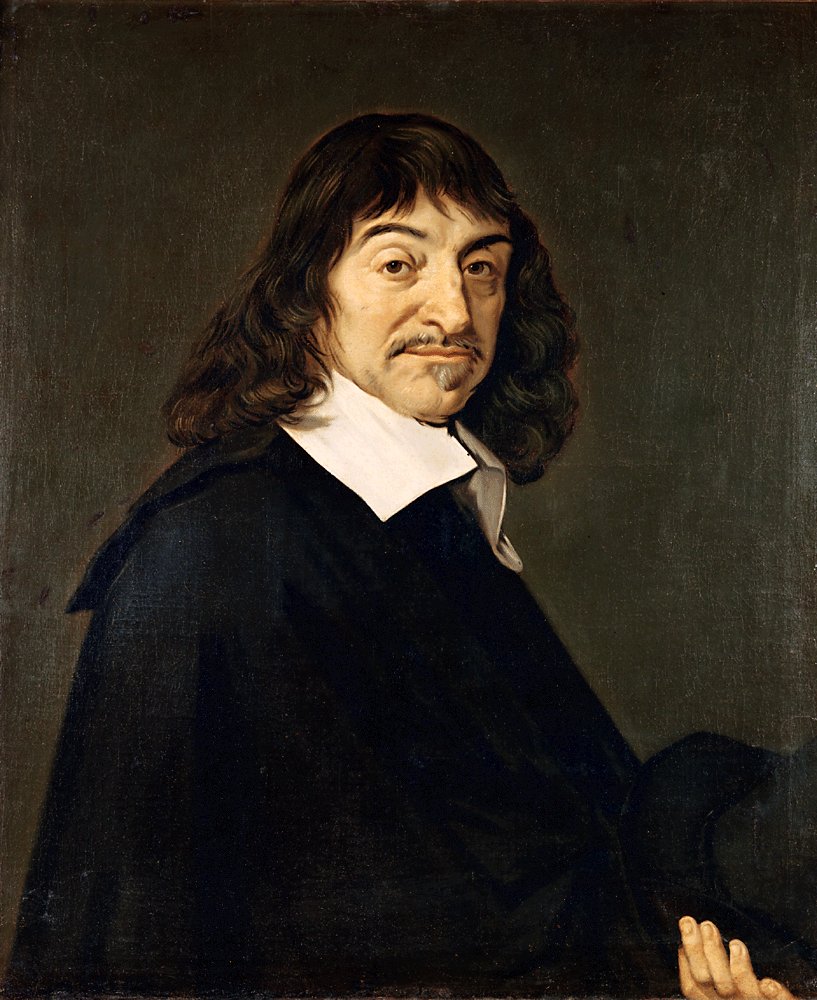

Portrait of René Descartes, by Frans Hals (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The identity – the fundamental personhood – of the one suffering from a heart condition is never in question because of the heart condition. On the other hand, a clinically depressed person can be defined by the illness in ways that unfairly characterize them as unreliable, too emotional, or otherwise defective. If I am my mind, and my mind is diseased, I am diseased – diseased in a way that is far more intimately “me” than a heart condition.

On one hand, this makes sense. We only metaphorically make the heart responsible for good and bad decisions. We literally make the person, who is most intimately associated with the mind, praiseworthy or blameworthy. When that person is mentally ill, we are more likely to consider that individual untrustworthy, irrational, and so forth – regardless of whether we’re justified in doing so.

Illness of any sort can negatively impact one’s mood, thinking, and behavior. Chronic conditions compound these effects.

On the other hand, effectively demeaning someone because of a mental illness fails to account for the complexity of the individual. A mentally ill person, depending on the severity of the illness, can have robust relationships, work consistently, reason, and reflect on their own condition. Insofar as that person is ill, they suffer – and a major goal of medicine is to alleviate suffering and cure, whenever possible, the cause. That is what is at issue for a mentally ill person, not their identity and thus also their value.

Even though we now associate “mind” with “brain” – and we have begun to understand that our complex physiology contributes to the various states and activities of consciousness – we continue to use “mind” as if it were something separate from the rest of us. The consequences have often been devastating for people who are unwell, their loved ones, members of their communities, and others.

At the very least, separating the mental from the physical implies different causal mechanisms are at work when one person suffers from, say, bipolar disorder, and another from heart disease. We don’t demand that the person in cardiac arrest get a hold of themselves, but we are likely to look askance at the person whose behavior is abnormal, even if they have as little control over their condition as does the heart attack victim.

Let’s Stop Faking Normal

Derision and repugnance are particularly cruel features of how stigmas are perpetuated in various social practices, from our ordinary language to popular culture. We often use “crazy” and “insane” pejoratively, and we lack a clear and widely accepted understanding of various disorders and their symptoms. Consequently, we don’t know when it’s appropriate to tell someone to “get a grip” and when it’s appropriate to offer support.

Should I be skeptical, for example, of a student who tells me they can’t come to class because they’re overcome by social anxiety or are trying to adjust to new medications for paranoid schizophrenia, or should I believe them and ask how I can help them work on the material outside of class? If the former, why? What grounds do I have for being skeptical? I don’t know what this individual’s life is like, what challenges they face at home, how they grew up, what pressures they’re under to succeed while holding down a job so they can live and pay for school. Why shouldn’t I trust them? What is to be gained from disbelief or dismissal?

French psychiatrist Philippe Pinel (1745-1826) releasing lunatics from their chains at the Salpêtrière asylum in Paris in 1795 (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

A friend once told me about attending a dinner with a handful of colleagues at a conference. As she sat down, she noticed one attendee didn’t have any arms. All the table settings had forks and knives – the stuff people with arms take for granted. My friend was concerned and asked if the colleague wanted the place settings removed. “I’m fine,” the colleague responded. “I’ve never known anything else.”

The person born without arms may observe those who have them, but they don’t live in arms – it’s not what life is like for them. Now consider the person with mental illness. Whether they’ve always lived with a certain condition, or developed it in their teenage or adult years, that person lives in the illness. Another way to put it is that the illness is a state of consciousness for that person, just as armlessness is the bodily state of someone without arms.

Life is hard under the best circumstances. A world in which groups are demeaned, diminished, or dehumanized for reasons that are morally irrelevant is nothing new. But it need not always be this way.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct instructor at the University of Rhode Island, Community College of Rhode Island, Salve Regina University, and Providence College. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. She lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.

Title image credit: Adobe Stock