The mother of computer programming, Ada Lovelace, had a celebrity father, Lord Byron, who was as famous for his wild affairs as he was for his exquisite poetry.

◊

When Ada, Countess of Lovelace, died in 1852, there was little notice of her passing outside aristocratic Victorian circles and the small group of engineers and mathematicians she associated with in her final decade. Some will have noted her scandalous parentage, being the only legitimate child of Romantic poet and firebrand Lord Byron.

Her life work, a long essay evaluating the theories of Charles Babbage, inventor of what’s regarded today as the first mechanical computing device, was soon forgotten. Babbage’s amazing machine never got past the working model stage, and Ada’s brilliant understanding of the capabilities and potential of his so-called “Difference Engine” was overlooked for nearly a century.

Learn more about Ada Lovelace in MagellanTV's Calculating Ada: The Countess of Computing.

Those notes and guide for the possible uses of Babbage’s machine are now widely considered to be the first computer program. Her fascinating biography is told in the Magellan TV documentary Calculating Ada: The Countess of Computing. And while the film sheds light on her adult ability and accomplishment, it passes lightly over her early childhood when Ada was, for a time, the most famous baby in England – the infant child at the center of the bitter legal separation of her parents.

Her mother, Annabella Milbanke, was the daughter of a baronet and member of Parliament. Ada’s father was George Gordon, Lord Byron, one of the greatest of England’s poets and, at the time, second only to Napoleon as the most notorious person in the world.

Lord Byron’s brief life, scandalous affairs, and lasting literary fame cast a long shadow over the life of his daughter, and gave impetus to her own unconventional contributions to what was rapidly becoming the modern world.

Byron Gains the Title ‘Lord’ at Age 10

The boy who would become the sixth Baron Byron was born in London in 1788. His father, John Byron, was an officer in the Coldstream Guards and a notorious womanizer and spendthrift. After divorcing his first wife he married the Scottish heiress Catherine Gordon and proceeded to dissipate her fortune before the two separated. He died in France, age 34, when his only son was three.

Young George Gordon Byron was marked at birth with a club foot and lived with his mother in genteel poverty in rural Scotland for a decade. Catherine Byron, clearly suffering from her husband’s abuse, was prone to depression and bouts of rage that were sometimes directed at her son and his perceived deformity, a condition that would mortify him throughout his life.

Everything changed when, at age 10, young George became the sixth Baron Byron at the passing of his great uncle, whose son and grandson both died before they could inherit the title.

Another wild spendthrift, and a notorious duelist, the fifth Lord Byron killed a neighboring landowner following a pub argument over the size of their respective estates.

The story goes that young George burst into tears when told by his schoolteacher that he had gained the title Lord. He and his mother left Scotland to live near the traditional family estate in Nottingham. Alas, his great uncle had bankrupted the baronial accounts and all but ruined his two ancestral homes and grounds, a legacy of debt that the latest Lord Byron would only add to.

Lord Byron at the publication of his first poetic works, ca 1805. (Image credit: unknown artist/Wikimedia)

Educated first by private tutors, Byron was sent to Harrow, an elite boarding school, at age 13. There, he excelled at swimming and demonstrated a precocious literary talent, publishing a book of verse at age 17 during his first year at the University of Oxford. Two other highly regarded volumes followed in the next four years as the young lord otherwise drank to excess, boxed and swam, and chased women, while racking up enormous debts to pay for it all.

In 1809, he left England on a two-year grand tour, even as Europe was torn by the Napoleonic wars. Deftly circling the battle zone, Byron traveled across Spain, the Mediterranean islands, and Italy before reaching Greece and then returning home.

Back in London in 1811, Byron wrote a book-length poem featuring scenes from his travels as experienced by a young man closely resembling himself. A heady mix of world-weary philosophy, heroic ideals, and lyric beauty, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage was an unexpected sensation, selling out its first printing in three days. As Byron wrote years later: “I awoke one morning to find myself famous.”

The First Modern Celebrity

Byron has been recognized as the first modern celebrity, famous for his dashing good looks and personal life as much as his poetic ability. He was also part of a trend. Thirty years of revolutions (in America and France) and Napoleonic wars had imposed a rigid sense of order and sacrifice in Britain that made readers there ready to accept temperamental rebels and visionaries like Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and William Wordsworth. By 1819, they had all published major poetic works, and became the vanguard of an artistic movement that prized romantic personal freedom and imagination over tradition.

That Byron wrote some of the finest poetry in the language, sat in the House of Lords, was drop-dead good-looking, went to all the cool parties, and belonged to all the right clubs gave him a magnetic appeal in the popular press. Think of a cross between Mick Jagger in his prime and the Prince of Wales and you’ll have some idea of Byron’s contemporary appeal.

Byron in Albanian dress, by Thomas Philips; a portrait made after the poet returned from his grand tour across the Mediterranean to the Ottoman Empire. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

He also displayed signs of what we might recognize today as bipolar disorder, rapidly cycling through bouts of deep melancholy and wild high spirits. His romantic and sexual interests were directed to both women and men – the latter feelings having, of course, to be indulged in secret and, for Byron, shame.

Thanks to a strict Calvinist upbringing, Byron was certain of his own damnation from an early age, wracked by guilt even as he openly defied Britain’s moral order.

Things came to a serious pass in 1812 when the 24-year-old lord embarked on a very public affair with a married woman, Lady Caroline Lamb, who later called her ex-lover “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Their displays, combined with Byron’s dissolute lifestyle and astronomical debts, prompted their mutual friend, Viscountess Melbourne, to suggest that her 20-year-old niece, the heiress Annabella Milbanke, might settle the heedless lord in a good marriage.

Byron’s temperamental opposite, Annabella was a pious, intelligent, and rosy-cheeked young woman who would pass her affinity for mathematics to her only child, Ada. Fatefully, she turned down Byron’s first proposal. Hurt by the rejection, he began a romantic liaison with another married upper-class woman, Augusta Leigh, who was also his half-sister.

The Scandal of the Century

Five years older than her half-brother, Augusta had little contact with him until 1813. She was by every account tenderhearted, good-natured, and lonely. Her husband, a first cousin, was a lieutenant colonel, and compulsive gambler, who was frequently away at his army post. The mother of three when she and Byron began spending time together, there is every reason to believe that her fourth, a girl born in 1814, was a product of their union.

This very dangerous liaison, which remained close, albeit platonic, after the child’s birth, would stay hidden only for a while. Byron, who had kept in touch with Annabella Milbanke, proposed again and was this time accepted. They were married in January 1815. Predictably, it was a disaster nearly from the start.

Drinking heavily, beset by debt collectors, and likely overwhelmed by unresolved feelings for Augusta, Byron plunged into a series of black moods that his new wife could not alleviate. Alternating periods of great affection with bitter quarrels and bizarre behavior that included him stalking around the house at night with two loaded dueling pistols, the newly pregnant Annabella came to believe her husband was insane.

Lady Byron was shocked to discover among her husband’s posessions a small bottle of laudanum, and a copy of Justine, an erotic novel by the Marquis De Sade.

Annabella invited Augusta to stay at the Byron home in London, where they bonded over their shared concern for the poet’s well-being. Augusta’s presence only increased Byron’s turmoil, and he began hinting darkly to his wife the true nature of his relationship with his half-sister, something Annabella at first blamed on his supposed insanity.

The child, named for her aunt, Augusta Ada, was born in December 1815. By now Byron was taunting Annabella with an open affair with a well-known actress, saying he intended to install his mistress in their home. His wife had had enough. She took Ada, age six weeks, to her parents’ estate on the pretense of avoiding a home construction project. Byron, under the impression the parting had been amicable, was angered and heartbroken when he received a letter weeks later from Annabella’s father insisting on the couple’s legal separation. He never saw his wife and daughter again.

By now, the gossip of friends and servants had spread rumors around London regarding Byron and his paternity of Augusta’s baby, widely understood as the true reason Lady Byron fled their home. Annabella came to realize the affair wasn’t part of a madman’s ravings. It was the scandal of the age.

Lady Jersey, in a bid to defend her friend, made a point of inviting Byron and Augusta to her Spring ball. According to one biographer, rooms emptied at the pair’s entrance. Men refused to shake Byron’s hand and only one person, a close female friend, spoke to them. A social pariah, Byron left England that same month for Switzerland and Italy after signing the separation agreement from Annabella. He would never return.

Byron’s Great Last Works, and His Martyrdom for Greece

Byron wrote some of his greatest poetry in the eight years remaining to him, including the book-length comic work Don Juan, a bestseller in England published in annual installments, about the martial and sexual misadventures of a handsome young man adrift in the Mediterranean world; and the bitter political satire The Vision of Judgment. He befriended another upper-class English outcast in Switzerland, Percy Shelley, whose wife Mary famously based the tragic hero of her novel Frankenstein on the dangerous-to-know lord.

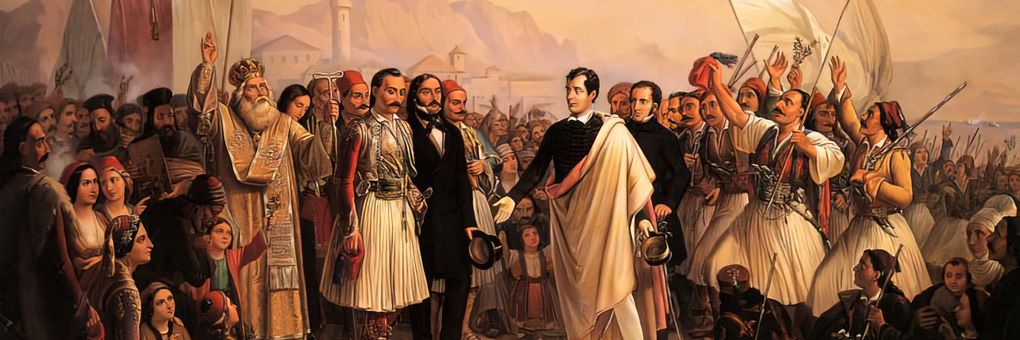

In 1823, Byron, who had mixed in anti-Austrian revolutionary circles in Italy, became actively involved in the cause of Greek freedom from the Turkish Empire. He brought money and guns to fight in the war for their independence, and died, age 36, in Missolonghi, Greece, in April 1824. By then a physical wreck, the poet caught a fever and was bled to death by his doctors. He remains a Greek national hero to this day.

Annabella, a capable mathematician in her own right (Byron called her his “Princess of Parallelograms”) made sure Ada was privately educated in the sciences so as to form a character as distinct from her infamous father’s as possible. The young Ada Lovelace’s mathematical skills were not only equal to Byron’s poetic gifts, she shared his ability to regard the world in creative, unconventional, indeed revolutionary ways. Nearing her own death from cancer, also at the age of 36, she asked that she be buried next to him in the Byron family crypt, where the two can be found today.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.

Title image: Lord Byron at Missolonghi, by Theodoros Vryzakia (National Gallery, Athens)