People have been thinking about nothing for a very long time. Does that make nothing . . . something?

◊

Is doing nothing the same as not doing something? If so, what does doing nothing look like? Is zero the same as nothing? If so, how can nothing be a placeholder?

These were just some of the questions a bunch of 5th graders – yes, kids! – recently asked a friend and colleague, who was leading a Philosophy for Children session at a local elementary school. Kids are natural philosophers – curious, open-minded, and willing to pursue strange ideas.

Not surprisingly, talking about nothing turned out to be a whole lot of something. You can’t do nothing, they concluded, since doing implies action. Moreover, zero, they said, works one way when thought of as a value, and another when thought of as a function. That’s a lot of pretty sophisticated talk about nothing from grade school kids.

Physicist Jim Al-Khalil walks you through everything and nothing.

Think Nothing of It

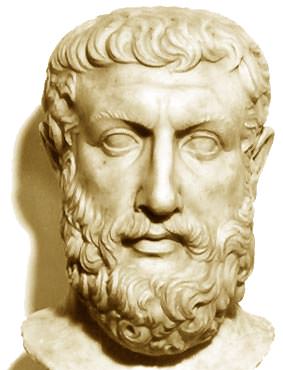

Kids aren’t the only ones interested in nothing. In fact, adults have been thinking about nothing for millennia. In the 5th century BCE, Parmenides, who lived in what is now southern Italy, laid out a mind-bending argument against the reality of nothing. Reality cannot be both what is and what is not. Our ordinary ways of talking about it, however, include what is not – that is, nothing.

More specifically, we believe that what we experience is real – things like trees and chairs and fish and clouds. At the same time, we accept that trees begin as seeds, grow, and eventually decay. Clouds pass and dissipate. There are things and no-things. What we’re saying about reality, as these examples show, is that it both exists and doesn’t exist.

Bust of Parmenides (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

To say, then, that nothing is somehow real is, on Parmenides’s line of reasoning, illogical. Reality exists or does not exist. It’s impossible that reality does not exist. So, reality must exist.

Consider what happens when you think. You think about something. There is an object of that thought. But nothing can’t be an object of thought – to say that you’re thinking about nothing involves a contradiction. So, what-is-not is impossible.

Among the implications Parmenides draws are that change is impossible. No creation. (Sorry, theists.) No Big Bang. (Sorry, physicists.) No mutating genes. (Sorry, biologists.)

All for Nothing

Parmenides’s successors have struggled with nothing ever since. Plato generally agreed that ultimate reality is eternal and immutable, graspable only through pure reason. On the other hand, Plato also thought the reality you and I experience is largely illusory, fluctuating as it does in various ways. Aristotle agreed that you can’t get something from nothing (‘out of nothing, nothing comes’) but disagreed that change is illusory. Space and matter exist, where the former is a receptacle for the latter. Indeed, most theorizing about nothing had more to do with emptiness than non-being.

Some philosophers of language tried to resolve the issue with nothing by recourse to distinguishing among naming, referring, and meaning. So, a name – say, Pegasus – has meaning even if it doesn’t refer to anything that exists (as a physical object, at least). We can describe the concept of Pegasus without committing ourselves to any correlate in reality.

If we can do the same for “nothing” as a term, we end up with a word that has meaning in contrast to objects, such as absence or privation. Someone is absent from work; a door lacks a working lock. We can understand the logical structure of language when we suspend judgment about existence. The sentence, “All werewolves are scary creatures,” has the same logical form as “All dogs are animals.” The existence of werewolves and dogs isn’t relevant to the logical form of the sentence.

Philosophers ranging from the ancient Greek Atomists (Leucippus and Democritus) to the 19th century German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel have had a lot to say about nothing.

In both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, there are similar threads of thinking about “nothing.” For example, the Buddhist non-self (anatta) is akin to the Western “bundle theory” of the self. Both reject the view that there exists some underlying substance or soul that is human essence. Instead, the self is a fluctuating collection of properties – perceptions, feelings, and so forth.

There’s Nothing to See Here

What if there is no nothing? What if the universe, to borrow from philosopher Bertrand Russell and physicist Sean Carroll, is just a brute fact whose existence cannot be explained in terms of something coming from nothing? What do scientists have to say about “nothing”? Why, given that science proceeds from observable data, even talk about nothing?

Physicist Jim Al-Khalili, for example, tells us that the universe is mostly nothing. It is a vacuum or void. In one sense, then, when physicists talk about “nothing,” they do not refer to non-being, but rather space devoid of particles – something like Aristotle’s view. Apparently, most of the universe is airless space. As Al-Khalili points out, “a vacuum is nature’s default state.” You can ring a bell in a vacuum and not hear it; but you can see it ringing, so light still exists.

.jpg)

Physicist Jim Al-Khalili (Credit: Andy Miah, via Wikimedia Commons)

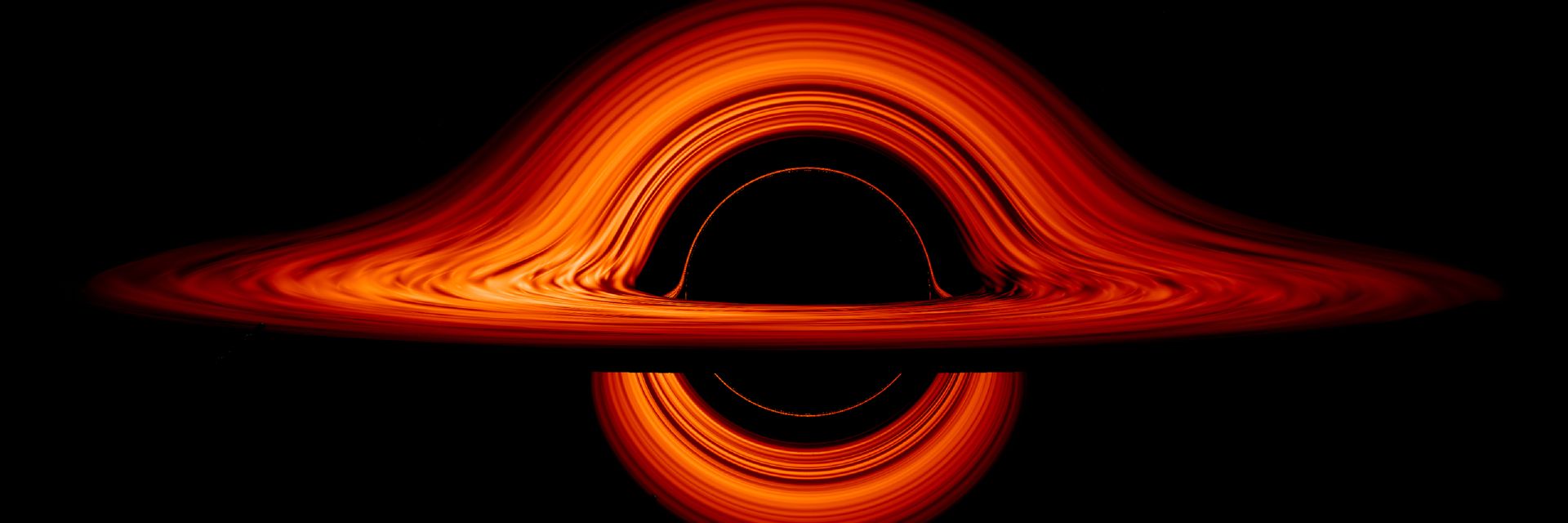

What about black holes? Are they closer to nothing than a vacuum? Maybe, but they’re still something – they’re not non-being. Instead, NASA tells us, black holes are “huge concentrations of matter packed into very tiny spaces.” (Furthermore, they’re not even holes!) Whatever gets close enough is sucked right in, including light, which is why the area looks black.

Particle physics may nevertheless give us a more promising candidate for proving nothing is real. After all, if electrons and anti-electrons ever met, they’d annihilate each other, disappearing completely. But if that’s true, how did we end up with a universe of matter?

Quantum “foam” is the nothing out of which pairs particles – matter and antimatter – “blink” into existence. This, physicists say, is the result of combining Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle with Einstein’s equation (E = mc2).

In any case, the mere absence of objects is not nothing. Even so-called zero-point energy, the lowest-energy point possible in spacetime, isn’t observed in quantum fields as such. In other words, motion does not cease. We could also posit that a universe without matter and energy is still . . . a universe, an empty apartment waiting to be furnished, not non-being.

So, zero-point energy is a metaphor, as are fields, waves, vacuums, strings, and foam – metaphors all, which is a curious way to articulate scientific conclusions. Then again, metaphors do a fair amount of work to help us get as close as we can to thinking directly about monumentally difficult features of reality.

Not for Nothing

By definition, nothing is not provable. Despite the conceptual problems associated with thinking about it, “nothing” is a wonderful all-purpose term whose meaning does not elude us. What are you thinking about? Nothing. What are you doing? Nothing. What happened? Nothing. What is that? Nothing. What’s wrong? Nothing. What’d you eat? Nothing.

Some, like Shakespeare, have done wonderful things with nothing. Not only is there not much ado about it, but also, as Macbeth has it, nothing is what is not. (Maybe Shakespeare read Parmenides?) Nothing is versatile. The scientists have shown us that, but so also have the forgetful, the silent, and the dead.

Clearly, nothing is very popular – perhaps almost as popular as Nobody. Aside from Beckett’s Godot, the characters in Seinfeld, and maybe Billy Preston in his hit single, “Nothing from Nothing,” Nobody is the only likely candidate to know anything about nothing.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct instructor at the University of Rhode Island, Community College of Rhode Island, and Providence College. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. She lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.

Title Image: Black hole’s accretion disc (Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/Jeremy Schnittman, cmglee, via Wikimedia Commons)