Scent could be the sense we find easiest to ignore. Is it, in fact, more consequential than we realize?

◊

So much is different since 2020, when COVID-19 first became a global issue and changed life as we knew it. It changed the way we work, play, care for ourselves, and eat. It changed how a generation grew up and came of age. It had major economic impacts, including contributing to record inflation globally. But the pandemic has also had an impact on something seemingly smaller and, perhaps, weirder: how we smell.

And no, I’m not just talking about the coronavirus’s infamous ability to interfere with our olfactory sense. In the years since the pandemic, perfume sales have spiked dramatically: “In 2023, the $64.4bn global fragrance market recorded double-digit growth across both premium (+12.2%) and mass (+10.8%) markets, according to Euromonitor International.”

Even now, in 2024, fragrance remains the fastest-growing sector of the beauty industry, despite the industry’s typical stability. As analyst Larissa Jensen observes, “The beauty sector, which includes makeup, skincare, and hair care, tends to be resilient regardless of broader economic conditions. We spend when we’re feeling good and when we’re feeling down. If the economy is in a slump, we buy low-ticket luxury to boost our mood. It’s an emotional industry. But fragrance – it’s like the power of scent is unquestionable. It’s nostalgia.”

Stream this MagellanTV documentary to learn more about Coco Chanel's iconic perfume.

The Underestimated Sense

In some ways, it’s counterintuitive to emphasize the power of scent in this way. Most people, if asked which sense is the most important, the most powerful, would say sight or even hearing, but surely not scent.

Scent is really more influential than we realize, and it’s deeply misunderstood. For one thing, many of us assume that, compared to other animals, humans have a relatively bad sense of smell. In fact, our olfaction is actually quite discerning. The difference mainly lies in the fact that unlike dogs or other animals known for their acute sense of smell, our noses are relatively far from the ground. But that doesn’t prevent us from putting our noses to good use: according to Pamela Dalton, a scientist at the Monell Chemical Senses Center, “we can smell something when there are only one or two parts of a fragrance material per billion parts of air. Dogs may be sensitive to a range of compounds, but humans have much more sensitivity to a much more diverse set of chemicals.”

Perhaps one reason we take scent for granted is that its impacts are largely pre-conscious. If you’ve ever walked through a scent cloud produced by a batch of fresh-baked cookies and instantly found yourself transported back to a childhood experience, you know all about how scent can transport us into a memory before we even realize what’s happening. How is this possible?

Unconscious Patient (Allegory of Smell), Rembrandt, oil-on-board, c. 1624 or 1625 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Unlike other senses, which are routed through a brain structure called the thalamus before being processed further to become consciously associated with memory and emotion, scent skips the thalamic waystation. Instead, as Colleen Walsh explains in the Harvard Gazette, “Odors take a direct route to the limbic system, including the amygdala and the hippocampus, the regions related to emotion and memory.” For this reason, scents are uniquely able to evoke memories and emotions even before they’ve risen to the level of conscious awareness.

The Vocabulary of Scent

Describing the scents we do notice reveals another problem: the simple fact that most of us know so few words to describe how things smell. While we can say that a sound is “clear” or “screechy” or “soft,” and we have an almost unlimited vocab for visual stimuli, the adjectives we use to describe scent are woefully limited for the general population. How can we even begin to tap into the power of scent if we don’t have the words to describe the experience of smelling?

This is a problem that those professionally involved with the science of scent have had to remedy. “Noses” – experts in the perfume industry who identify and capture different olfactory characteristics, and use them to create fragrance compositions – have developed a detailed language for scent.

(Credit: cottonbro studio, via Pexels)

(Credit: cottonbro studio, via Pexels)

The ABCs of scent begin with “notes,” single facets or ingredients in a scent, like a single spice in a recipe. A scented sunscreen might include a coconut note, for example. The next step up from a note is an “accord,” which is a blend of notes. If notes are like individual spices, accords are spice blends. For example, a central accord in men’s perfumery is the “fougere” accord, which comes from the French word for “fern”. Fougere accords recreate the earthy, damp, and dark scents of a forest, using notes like oakmoss, lavender, and coumarin, which comes from tonka beans.

There are also certain scents that would seem to be literally one-note, but are in fact accords: This is typically the case with scents that cannot be directly extracted from their source. A “fig” note, for example, cannot actually be extracted from a fig, so perfumers have to reverse-engineer the scent of a fig using other scents. Perfumer Gino Percantino describes the process this way:

Fig is always fun for me because I often work from some of my best coconut, just coconut. So I’m not talking about like pina colada with pineapple and all that. Just the creamy kind of coconut. If you dial it back and put more pulp into it, a little more juiciness into it, a little more green with some extra woods, cause you want that stemy element of it. And then you’ve turned a coconut into a fig.

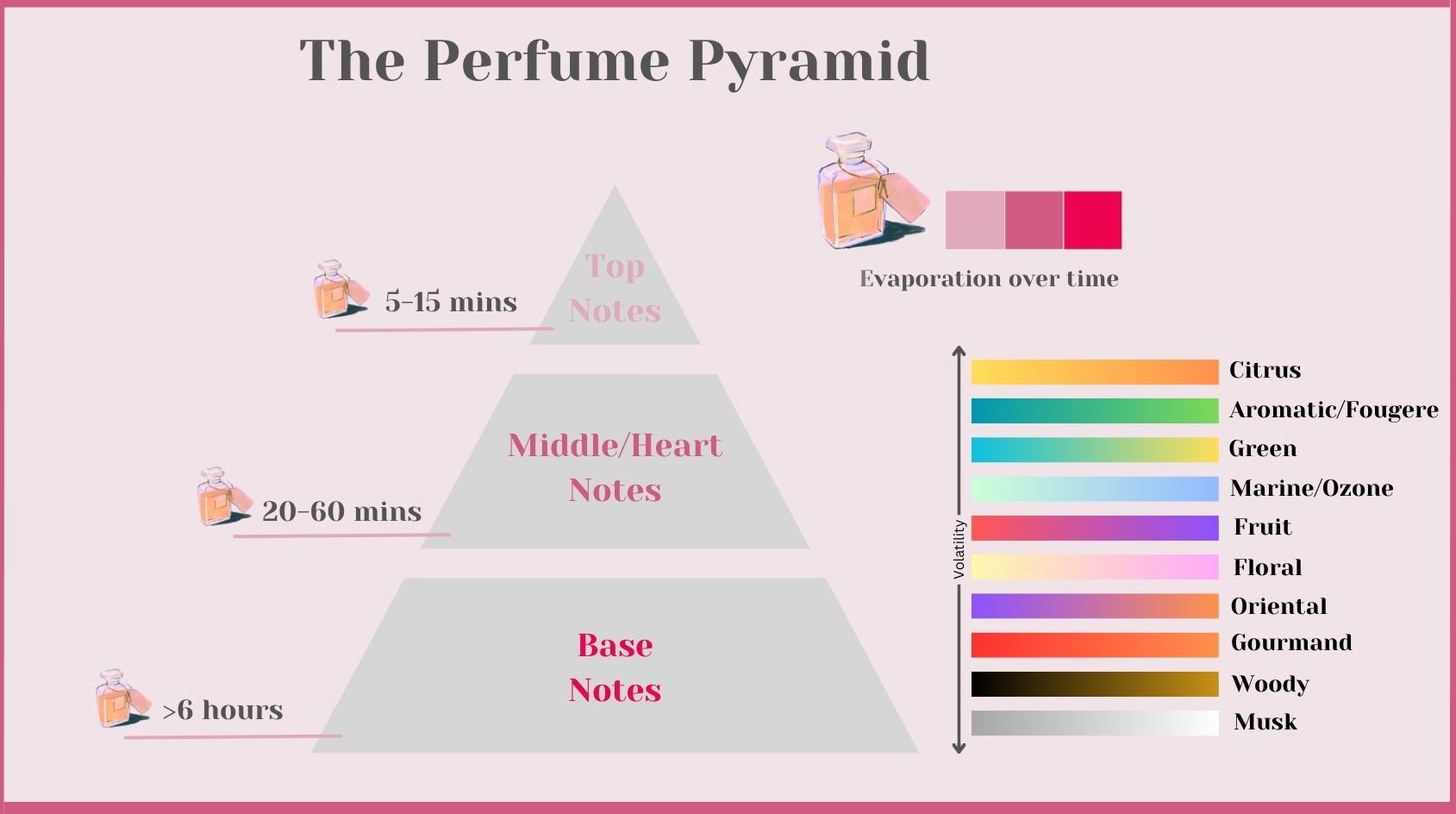

With this huge library of smells, both naturally extracted and artfully reconstructed, noses can create nearly unlimited fragrances. These fragrances are typically described and broken down into top notes, middle notes, and base notes – these notes together make up the scent’s fragrance pyramid.

A perfume/fragrance pyramid helps to describe a scent experience using top, middle, and base notes. These notes, and the scent overall, can fall into several categories, from “citrus-y” to “musk-y.” (Graphic created by Sari Wagner using Canva.)

A perfume/fragrance pyramid helps to describe a scent experience using top, middle, and base notes. These notes, and the scent overall, can fall into several categories, from “citrus-y” to “musk-y.” (Graphic created by Sari Wagner using Canva.)

This perfume pyramid includes not only each of the individual notes involved in a scent, but also charts the progression of the experience of a fragrance over time. This is because some notes are more chemically volatile than others, meaning they fade faster, while other notes linger for hours after application. So, while the top notes are your first impression of a fragrance, the first thing you smell after the alcohol carrier dries down, the middle/heart notes are considered the “core” of a scent. They present as the top notes begin to fade, and add body. After about an hour passes, the middle notes make way for the base notes, the “foundation” of a scent. This is what you can smell lingering on your skin hours after applying a scent. They are the least volatile notes, and tend to warm and deepen on the skin.

There are seven main olfactory families: citrus, floral, chypre, aromatic, woody, amber, and leather.

Altogether, the top, middle, and base notes describe in detail a scent experience, and this formula can be applied to any scent to better understand it.

A Brief History of Noses

Perfume’s popularity may be resurging now, but the art of fragrance has a long history in Western and global society alike. This nostalgia, this ability to provoke strong emotions and even to transport, has been leveraged by artisans and chemists for centuries. Ancient Egyptians were so attached to their fragrances in life that, in death, they were often buried with small bottles of perfume alongside other essential belongings. These oils have turned out to be quite meaningful to present-day archaeologists, who have used them to decode the social status of mummified ancient Egyptians. Beyond the types of oils Egyptians might have chosen to be buried with, fragrance was also intimately involved in the Egyptian embalming process:

[After the mummifying process,] the body was stuffed with pleasant-smelling spices, like cinnamon, to help give the body a more lifelike appearance. Even the linen wrappings that went around the body were treated with materials like myrrh, cassia, and camphor oil. All of these elements had a pleasant scent, which was important because the Egyptians equated a pleasant smell with holiness.

In Europe during the Romantic Era, a process called “enfleurage” was used to leach the fragrance from petals prized for their precious aroma. The scents extracted in this process were dabbed on the skin to cover up body odor. At the time, it was thought that bathing was actually dangerous, allowing toxins to make their way from the bathing water through the pores and into the body. Perfumes became extremely popular for their ability to counteract the stench that would naturally occur from not bathing, and so scents in this period tended to be strong and fresh. Thus, in a very different way, perfume rituals of the 18th century, like those of the ancient Egyptians, were intimately tied to ideas about the body, about sickness and health, life and death.

(Credit: Jess Bailey Designs, via Pexels)

Perfume and the COVID Pandemic

It might seem that in the modern era, we have other, more advanced strategies for responding to sickness, and in many respects that is true. Today, germ theory tells us that bathing is vital to fending off illness, and sanitizing our hands played a major role in the COVID-19 pandemic response. We have also developed vaccines that can protect us from illness, and, during the pandemic, we used them to our great benefit.

But in some ways, our responses to the global drama of COVID-19 call to mind ancient responses to illness and death. Especially during a period when smell was hampered – whether by the virus itself or by masks which, while useful for protective purposes, shielded us from a host of engaging and informative smells of the outside world – many people around the world leaned on fragrance as a way to escape. Remember how perfume sales dramatically spiked immediately after the pandemic? There are many theories about why perfume popularity increased during this period, but a prominent one has to do with escape:

According to Firmenich COVID Studies, fragrances that conveyed a sense of cleanliness and protection played an important role in consumers’ lives, particularly at the beginning of lockdown, as did fragrances that delivered soothing comfort and serenity. The NPD Group added that parfum sales grew double digits for the year, as consumers showed a greater affinity toward longer-lasting scents.

Life, Death, and Perfume

Fragrance has always been involved in our most intimate rituals, from embalming to seduction, to the reduction of our natural body odors. After all, our sense of smell evolved for the most essential purpose: to keep us alive. It helped us distinguish between potential poisons and safe food, bonded mothers and newborns, facilitated connection between partners, and, some scientists propose, even helped us identify potential mates. As the least consciously-facilitated sense, it has the ability to emotionally and intuitively tie us to the mortal world, to the world where everything lives and dies – and where you can smell the difference.

Dive deep into the science of smell in this fascinating MagellanTV documentary.

Given perfume’s history, maybe it’s not surprising that we’re experiencing a surge of interest in fragrance today, post-COVID pandemic. We’ve come out of those years all too familiar with our mortality, and with the upkeep of being human. During the pandemic, we experienced a deluge of new smells: the alcoholic olfactory burn of hand sanitizer and cleaning fluid; the slightly rank body odor of overused sweatpants; the solar, aldehydic scent of fresh air at outdoor, socially-distanced gatherings. While it’s true that scent can be transportive beyond this mortal coil – there’s a reason perfume ads are often so surreal! – it can also root us firmly in the world around us.

Scent can indicate the funk of sickness – perhaps most undeniable for one woman who can actually smell Parkinson’s – or the clean warmth of health. During the pandemic, we all were offered a glimpse of our mortality, and scent played a role in that. Some chose to harness scent in response. While hand sanitizer and body odor clamored for our attention, begging to remind us of our terrifying situation, some of us utilized fragrance’s transportative potential to escape. In doing so, perhaps we were unknowingly linking ourselves to a lineage of humans using scent to stave off the many-scented reminders of mortality.

Ω

Sari Wagner is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. Originally from North Wales, Pennsylvania, she is a graduate of Kenyon College with a degree in neuroscience and studio art. She is passionate about sharing fascinating scientific findings and allowing everyone to reap the benefits of research.

Title Image: Adobe Stock