Like most things in U.S. history, the origins of today’s health insurance system are complicated.

◊

Imagine a child running through the tropical rainforest of a prehistoric island. Perhaps a handful of children are playing some 31,000-year-old version of hide-and-seek. Suppressed giggles and hushed voices are suddenly drowned out by a horrific scream. One of the children has fallen and been seriously injured – a broken left leg that will not heal and must be amputated below the knee.

Wait. A surgery? An amputation performed 31,000 years ago? That’s what scientists concluded from remains found on the island now known as Borneo in tropical Southeast Asia. If the findings are correct, at the time, human beings knew enough about anatomy and had sufficient technical skill to conduct life-saving medical procedures like amputations. Awful as it must have been – anesthesia, at least as we know it, wasn’t used until the mid-1800s – surgeries like amputations prolonged people’s lives, even in that long-past era. And, as we now understand, evolving healthcare is a hallmark in the development of civilizations.

Today’s healthcare systems are the result of thousands of years’ worth of advances in scientific knowledge about health problems like diseases and their causes. In addition, various changes in the way societies are organized and attitudes about health as a social concern contribute to the explanation of our current insurance-based funding for healthcare.

But how did that happen? How did humanity go from the earliest efforts to provide healthcare to today’s public and private systems? How did health insurance come about and why did vision and dental coverage get split off from coverage of the rest of the body? Why is prescription drug coverage separate from all other health insurance? These are big and complicated questions with equally involved histories, so let’s narrow our scope to how health insurance emerged in the U.S. to become unique among developed countries.

To learn more about challenges to the modern U.S. healthcare system, watch MagellanTV's When Big Tech Targets Healthcare.

The Origins of Health Insurance in the United States

That ancient child in Borneo didn’t have health insurance. (I know, that’s a “duh!” comment, but bear with me.) It’s not like the kid’s parents were eligible for Medicaid or had private health insurance through one of the parents’ employers. Presumably, someone in the social or family group was able to successfully amputate a limb, the child recovered, and apparently lived on for the better part of 10 years.

Today, the picture would be remarkably different. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The history of who gets what care – and why – is at least part of the story of health insurance. In the Western world, that history dates back at least four centuries. England’s informal practice of neighbors caring for their ill or disabled community members was codified in the Poor Law of 1601. This law, along with many of England’s common laws, was adopted by the American colonies.

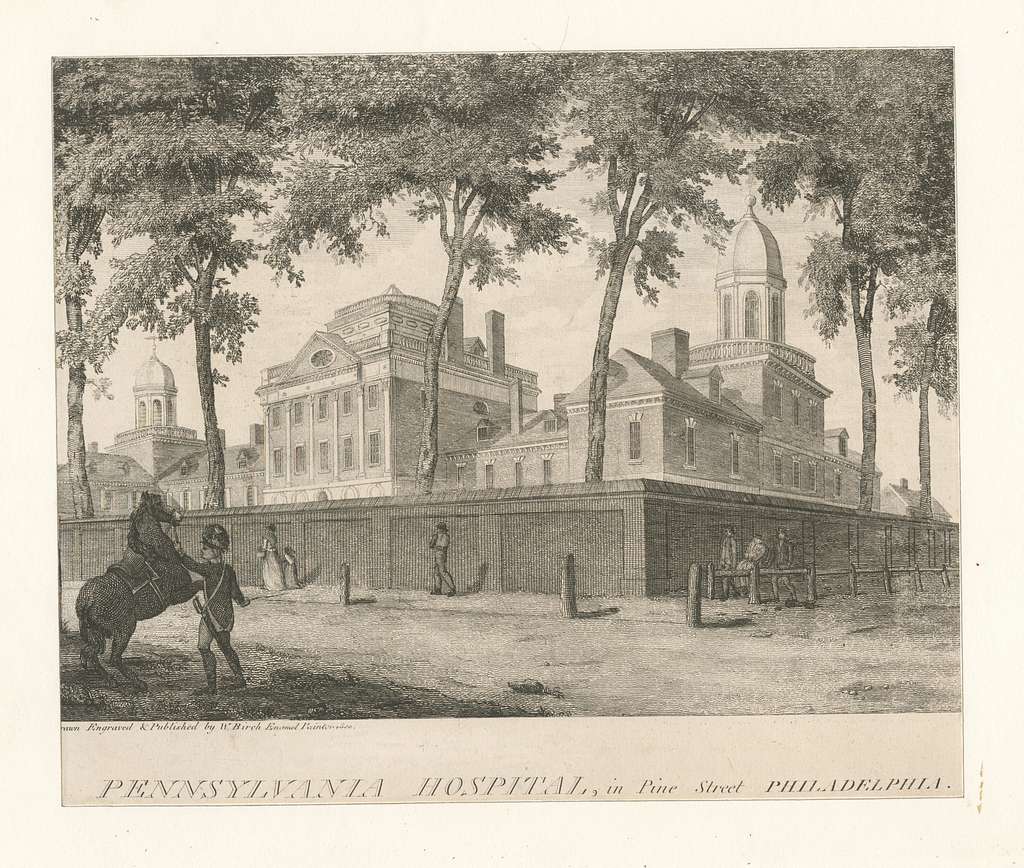

(Credit: New York Public Library Public Domain Archive)

(Credit: New York Public Library Public Domain Archive)

As communities grew, however, it became clear that a more formal system of care was in order. In 1752, Philadelphia opened the first voluntary (nonprofit) hospital, and, in 1773, Williamsburg, Virginia, opened the first mental hospital. The interest in public health coincided not only with population growth, but, beginning in the 19th century, with the realization that disease and sanitation were related.

Sanitation, Disease, and the Industrial Revolution

Before scientists found that inadequate sanitation set the conditions for both the causes of disease and their spread, the prevailing attitude toward illness was moral. In other words, illness was a sign of moral and spiritual failing – likely akin to the belief that poverty is a failure of moral character, rather than social conditions. The dearth of medical knowledge meant there was little evidence to counter these beliefs. So, though the thinking about disease expanded and, at least in the medical community, increasingly focused on empirical evidence, the old beliefs persisted.

With the rise of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-1800s came urbanization. People living in cramped, densely populated cities were more likely to contract and spread disease. In those conditions, quarantining and otherwise isolating ill people was nearly impossible. These same people were the working class and very poor, which reinforced the superstition about health and poverty. Still, health, having been established as a public concern, not merely a private matter, continued to develop.

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, which generated enormous numbers of severely injured soldiers – and which necessitated the development of, and innovations in, surgical techniques, nursing care, and research – the U.S. Army created the Hospital Corps, which contributed to the formalization of the incipient U.S. healthcare system.

Major Influences on the Development of Employer-Provided Health Insurance

Simultaneously, at least three developments factored into the initial emergence of health insurance: urbanization and industrialization, rising medical care costs, and employer efforts to prevent unwell and injured workers from turning to unions.

As hospitals improved (albeit largely unregulated), vaccines and antibiotics became more common. In addition, more treatments and therapies were developed for various conditions. These advances led those who could afford it to seek better care. Before then, those people didn’t spend that money partly because there just wasn’t much that could be treated.

With advances in medical knowledge and practice came improved efficiency in healthcare – and money to be made. Physician training and licensure bodies – think the American Medical Association (AMA), which, by 1899, had almost half of the country’s physicians as members – developed, in part, to meet the demand for the improved care. Such care, in turn, contributed to the organized practices we see today.

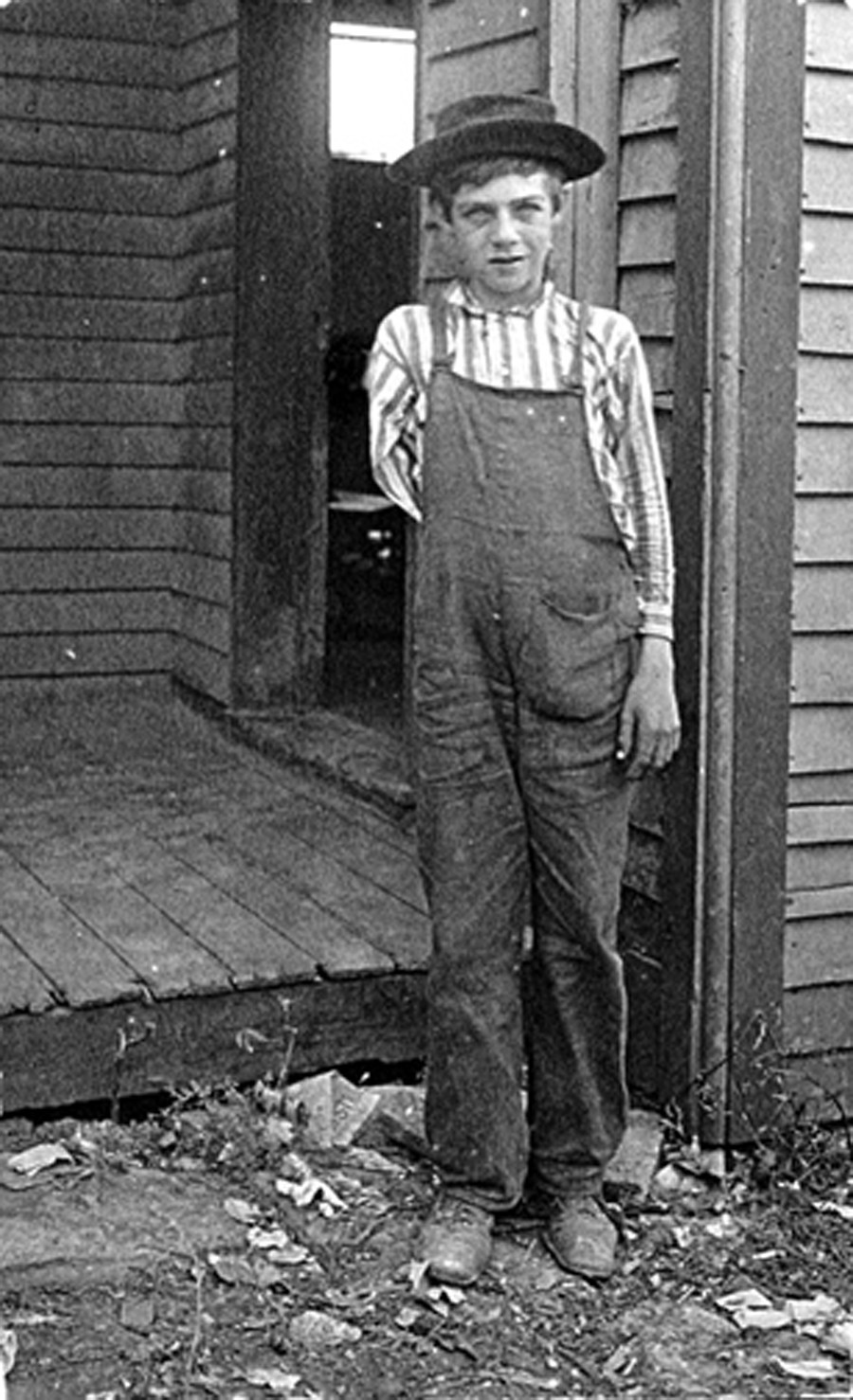

A child who lost his arm operating a saw in a box factory, 1909 (Credit: Lewis H. Hine, via Flickr)

A child who lost his arm operating a saw in a box factory, 1909 (Credit: Lewis H. Hine, via Flickr)

For example, some doctors set up a prepaid system in which those who could afford it paid small amounts over time, rather than a chunk of money all at once for an emergency. Childbirth became medicalized as hospitals marketed themselves as good places to deliver a baby.

In the late 1700s, “man-midwifery” was introduced by a Philadelphia physician. Though doctors had previously been called in to help with delivery complications, childbirth was historically facilitated by a midwife or nurse, the latter of which were invariably women.

With medical innovations, research and facility maintenance also meant healthcare costs rose. Before and during the formalization of healthcare practices, people paid for their medical services in a variety of ways. These included sliding scale fees for the poor, barter, charity, and mutual aid societies (like fraternal orders and unions). With the urbanization that accompanied the Industrial Revolution came not only the diseases spread by squalid and almost cheek-by-jowl living arrangements, but also workplace accidents.

What little employer-sponsored medical care existed had more to do with discouraging union membership in organizations like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), formed in 1905, than mitigation of hazardous working conditions and various health risks. Even then, however, monetary compensation for workplace injuries was mainly for loss of income, not medical coverage as a benefit in addition to wages.

Rise of the Modern Health Insurance Model

Prior to the first health policies issued in 1908, insurance companies were devoted almost exclusively to life insurance and pension plans for large businesses. At the time, health insurance was considered too risky. After all, if only unhealthy people sought health insurance, the cost of paying out to the ill and injured wouldn’t be offset by health policy holders who don’t file claims – what insurers call adverse selection. Moral hazard was considered another risk, namely that people would use their coverage to seek unnecessary medical treatments.

National Healthcare and Nascent Health Insurance Groups

There were efforts to enact a national healthcare system for people in the working class, such as one proposed by the American Association of Labor Legislation (AALL) in 1915. Even support from people as powerful as President Theodore Roosevelt, who had declared, “No country could be strong whose people were sick and poor,” could not move the legislative needle forward.

One reason the AALL proposal stalled was that, despite initial support, the American Medical Association backed out over a physician payment disagreement. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) also opposed the bill on the grounds that it would give the government control over citizens’ health and undermine worker unions and benefits. And, as the advent of World War I became the focus of national attention, the legislation fell to the wayside.

Of all the industrialized countries in the world, only the U.S. does not have a universal national healthcare program.

Remember, however, that nonprofit hospitals were open to novel ways of generating revenue, since private funding from sources like philanthropists and donations did not always cover operating costs. They needed income that would support, among other priorities, medical research, the cleanliness of the facilities, and improvement in medical practice. But if hospital beds weren’t full every night, these priorities would become vulnerable. At the same time, some groups of employees and some employers were interested in or had already entered into prepaid agreements with hospitals or clinics.

Doctors and students listen to their heartbeats, circa 1920 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Doctors and students listen to their heartbeats, circa 1920 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1917, physicians in Washington state created a coverage network called Blue Shield. For a monthly fee, lumber and mining camp employers provided access to medical care for their employees. It was a version of those direct patient-physician prepaid agreements that both doctors and those who could afford to pay found beneficial.

In 1929, a group of public school teachers in Dallas contracted with Baylor University Hospital for a set number of days of in-patient care annually for 50 cents a month for each member. The Baylor Plan would eventually become known as the Blue Cross nonprofit plan, a precursor to today’s Blue Cross Blue Shield. The Ross-Loos Medical Group adopted the prepaid coverage model to insure 12,000 Los Angeles Department of Water and Power employees and their families.

Around the same time, a significant number of European nations adopted compulsory national health insurance. But, in the U.S., both a lack of interest and pushback from unions, insurance companies, and physicians scuttled such plans. It was the Great Depression and then World War II that solidified what would become the modern model of health insurance in the United States.

The Great Depression

Despite the ravages of the Great Depression, Congress passed the Social Security Act in 1935, but without any health insurance component. Among other consequences, the Great Depression had practically emptied out hospital beds. Who could afford care?

In 1939, California physicians established the Blue Shield Plan, a prepaid service that mirrored the Blue Cross structure. Its roots, however, went further back -- to the employer-sponsored coverage for workers in the Pacific Northwest. By the end of the Great Depression, doctors worried that third parties would interfere with physician-set fee structures. They were also concerned about competition stemming from the growing influence of Blue Cross, not to mention ongoing calls for a national health service.

FDR signs the Social Security Act in 1935 (Credit: FDR Presidential Library and Museum, via Flickr)

FDR signs the Social Security Act in 1935 (Credit: FDR Presidential Library and Museum, via Flickr)

President Franklin Roosevelt’s interest in governmental support of citizens’ healthcare served as another motivation for doctors to accept the idea of health insurance. More specifically, some worried that federalized healthcare was a socialist system that would irrevocably alter their profession.

Cementing Employer-Provided Health Insurance: World War II and the IRS

With World War II came wage controls, which influenced employers to turn to fringe benefits like health insurance to attract workers. Another major step toward solidifying employer-provided health insurance as the main model for financing healthcare came in 1943 when the IRS declared employer contributions to health insurance exempt from taxes. In 1954, Congress codified the rule. These changes to tax policy precipitated enrollment surges.

Competing interests and needs, along with social conditions and the medical community’s capacity to treat more conditions, propelled healthcare coverage in the direction we experience today. In the post-war years, people continued to work on ways to provide health coverage, and employer-sponsored health insurance really took off. Health maintenance organizations (HMO), which arose in the 1970s and 80s, followed the physician-group model, with members having access to a network of doctors for a monthly fee.

Today’s labyrinthine system is clearly flawed – there are deeply problematic inequalities that negatively impact large numbers of U.S. citizens. For example, the monumental governmental effort to ensure that everyone has access to affordable healthcare – what became the Affordable Care Act – was met with deep suspicion and outright hostility, and the program’s implementation was hardly seamless. What we do about it in the coming years will likely reflect, once again, competing interests and needs, along with social conditions and the state of medical science.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. Among her relevant publications are essays in Mr. Robot and Philosophy: Beyond Good and Evil Corp (Open Court, 2017), Westworld and Philosophy: Mind Equals Blown (Open Court, 2018), Dave Chappelle and Philosophy: When Keeping it Wrong Gets Real (Open Court, 2021), and Indiana Jones and Philosophy: Why Did It Have to be Socrates? (Wiley-Blackwell, 2023).

Title Image: Adobe Stock