Artist Andy Warhol is universally recognized as a prime progenitor of Pop Art and its attendant cultural earthquakes of the 1960s and beyond. His reputation as personally reserved, even withholding, found root in his glacially cool, photo-based serial imagery, which erased the artist’s hand from the final product. But is Warhol’s art in fact impersonal? Evidence from his early life indicates that his canvases may be closer to Warhol’s life experience than he ever let on.

◊

Late one night in the spring of 1949, while most of Pittsburgh slept, two figures stepped quickly toward the bus platform. These two men – Andy Warhola and Philip Pearlstein – just graduated from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), were in a hurry to get aboard that Greyhound bus out of Pittsburgh and on with their lives.

By morning, the overnight bus had deposited them at Pennsylvania Station in New York City. Personal snapshots from that early period show two young men, dressed in jacket and slacks, leaning awkwardly against a railing in a city park, eyes averted from the peering lens of the inquiring camera. That was the mundane beginning of what can only be called a nascent cultural earthquake, even a “youthquake.” Philip Pearlstein went on to become a renowned painter, particularly of expressive portraiture, and Andy Warhola, well, after chopping off that European final vowel in a bid to seem more “American,” he became Andy Warhol.

The long drive through the blankness of the dark Pennsylvania night must have given them time to reflect. While we can only surmise what may have been on Andy’s mind, I believe we can safely assume that he was focused, in part at least, on his future. Perhaps he also took a rearward glance at his family and upbringing, and how the many ups and downs of his young life had prepared him for this moment.

Check out MagellanTV's Great Creators Collection

The Warholas of Pittsburgh: A Humble Start to an American Dream

Warhol’s father, Ondrej Warhola (Americanized from Varchola), a miner from the Carpathian Mountains region of current-day Slovakia, immigrated to the hills of northwestern Pennsylvania around the turn of the 20th century to make a better life for himself. After working in the U.S. for a few years, he returned to his village of Mikó (now Miková) in 1909 to court and marry Julia, who bore their first son, only to lose the child to illness.

In 1912, without Julia, Ondrej returned to Pittsburgh to create a home for her and their planned family. She joined Ondrej, now working in home construction, in 1921, and they lived together in a tar-paper shack with no indoor plumbing for the next eight years, during which they welcomed three sons to their family: Paul, followed by John, and finally, taking an Americanized version of his father’s name, Andrew.

As a child, Andy was prone to illness. He contracted St. Vitus’ Dance (Sydenham’s chorea), a disease of the nervous system that caused his limbs to shake uncontrollably. His complexion was also marred by red blotches that caused no end of suffering at the hands of classmates who called Andy “Spot.” His childhood illnesses caused him to miss much of third grade, and his doting mother, who had been an embroiderer in the old country, gave the young boy pencil and paper and encouraged him to draw. Julia treasured young Andy, knowing first-hand the potential price of childhood illness.

Andy responded so well to his mother’s guidance that the young student’s fifth-grade teacher recommended him for Saturday art-enrichment classes offered for free by the Carnegie Institute (now the Carnegie Museum of Art). Both of Andy’s parents supported their youngest to develop his skills, and he attended these classes for years.

Ondrej died unnaturally young, possibly of tuberculosis. Despite the family’s extremely limited resources, he bequeathed his small estate to his sons. The elder two divided his workman’s tools equally, and Andy received his father’s life savings, $1,500, in the form of a postal bond, to use for his education.

Andy was naturally shy and extremely self-conscious, personality traits acquired early in a difficult childhood of penury and privation. But despite enduring some desperate situations, the family was tight-knit and loving toward the infirm youngest child. Later, as a college student, he developed friendships with classmates who appreciated his skill and craftsmanship, and he worked on his degree in pictorial design with impressive vigor.

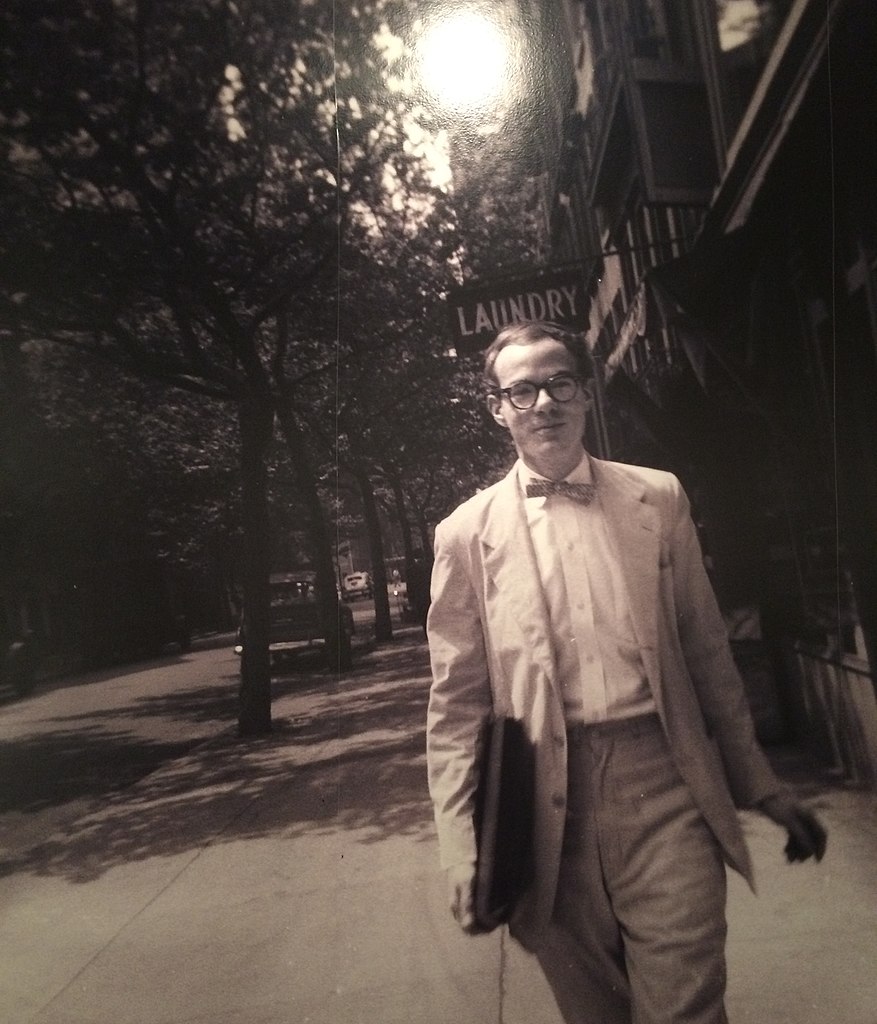

Andy Warhol, successful advertising illustrator, with portfolio, 1950 (Source: Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

While in college, Warhol had invented a mechanical means of turning a drawing into the basis for multiple prints, adding hand-drawn and painted finishing touches to make each multiple unique. This “blotted-line” technique allowed his finished work to retain the charm of his whimsical touch, along with the visible mark of the printing process in the blotted, broken lines.

As he increased in confidence, his collegiate work at times took on a sardonic edge. For his senior show, he submitted a work focused on his bulbous, blemished nose, titled, The Lord Gave Me My Face but I Can Pick My Own Nose, a witty work that nonetheless created such a stir it was nearly censored from the show.

Moving to New York City – Rapid Acclaim for the Young Illustrator

Warhola became “Warhol” when his first professional drawing was accepted for publication in Glamour magazine. His jittery, uncertain line, reflecting the energy and anxiety of the postwar “Atomic Age,” was perfect for the time, even prescient. Fashion magazine editors and art directors ate up this striking new look for their products.

Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines quickly gave him commissions, and eventually the shoe emporium I. Miller used his “blotted-line” drafting technique to rebrand its entire print advertising campaign. Andy found himself flush with cash for the first time in his life, and he liked what it could do for him.

Andy’s earliest experiments in what later became known as “Pop Art” included variations on the depiction of the U.S. dollar sign, a theme he would many years later return to.

In 1959, as an advertising illustrator, Warhol was making $65,000 annually. (That’s a cool half-million in today’s money.) That princely sum was more than enough to purchase a tony Upper East Side townhouse where he eventually made a stable home life for himself and his mother. Strikingly, the wholesome domesticity of their townhouse life together stood in stark contrast to the wild, drugged-out nightlife of his mid-1960s “Factory” that's so intimately associated with him in the public imagination.

Pop Goes the ’60s – in the Arts and Society

Following years of success in advertising illustration, Warhol turned his attention to blending advertising techniques – and the ads themselves – into fine art. Groundbreaking at the time, he was soon joined by a cadre of like-minded New York City painters and sculptors who were keen to break with abstract art and depict recognizable objects from daily life. Roy Lichtenstein’s comic-strip panels, Claes Oldenburg’s electrical plugs, and other shockingly quotidian objects forced their way into what was then termed “high art.”

Following his foray into dollar bills, he focused on other signs, symbols, and metaphors for contemporary life that gave him pleasure. In the poverty of his early youth, Campbell’s soup was a touchstone of familial warmth. As a treat, young Andy was allowed to choose which kind of Campbell’s soup Julia would serve the family for a meal. Tomato was his favorite. This inspired Warhol’s first succès de scandale, his “soup-can art.” He also recreated the green glass of multiple Coca-Cola bottles, which drew even more attention to him and his novel, daily life–inspired works.

Eight Elvises, 1963. (Source: fair use, via Wikipedia)

Now Warhol was using commercial printing techniques, along with hand-applied paint, to play with the removal of the mark of the artist’s hand, a tenet of Abstract Expressionism that Andy was drawn to tweak. He used photographs, rather than drawings, as the basis of his silk-screened canvases, repeating the images to highlight the failures of the mechanical process. In a sense, these “mistakes” – overprinting, out-of-register color – highlighted the “human touch” of the intentionally misapplied paint.

On the Abject in Art – Warhol’s Choice of Subject Matter

Warhol claimed he wanted to be transparent, wanted to be plastic, wanted to be a machine. The self-erasure that he practiced, at least in public, caused the humanity of the individual Andrew Warhola to recede so the legend Andy Warhol could flourish. But there are ample clues, particularly in his early work, that reveal some of the formative experiences, and traumas, that served as inspirations.

Self-negation is evidenced in his Before and After (Nose Job) canvases of 1961, which corresponds to his own 1957 “nose job,” the first of several attempts to shave down the size of his nose as well as to address a nasal skin lesion. This erasure of the self combines with an emphasis on death and destruction. In fact, “Death and Destruction” is the title of a series Andy worked on for several years in the early 1960s. And why did he do this? When asked, he slyly responded, “You’d be surprised how many people want to hang an electric chair on their living-room wall. Specially if the background color matches the drapes.”

Examples of death imagery from this period abound: Suicides, car wrecks, plane crashes, race riots, a series of electric chair images, all present explicit, morbid imagery. There was even an attempt at public art. The State of New York commissioned Andy to create a work for the exterior wall of the Empire State’s exhibit at the New York World's Fair of 1964–65. Andy produced a silk-screen he called “13 Most Wanted Men,” portraits of criminals wanted by the law. Perhaps predictably, New York state authorities rejected the work. Andy’s quiet revenge for the censorship? He chose his favorite color of the time – silver – to be used to paint over and disguise the 13 men’s mugshots.

Moreover, his celebrity portraits of the era are tinged with death and grief. His portraits of Jacqueline Kennedy depicted her in the days immediately following the death of her husband, the president. The career-making, color-drenched multiples of Marilyn Monroe were begun just after news of her 1962 suicide reached the public.

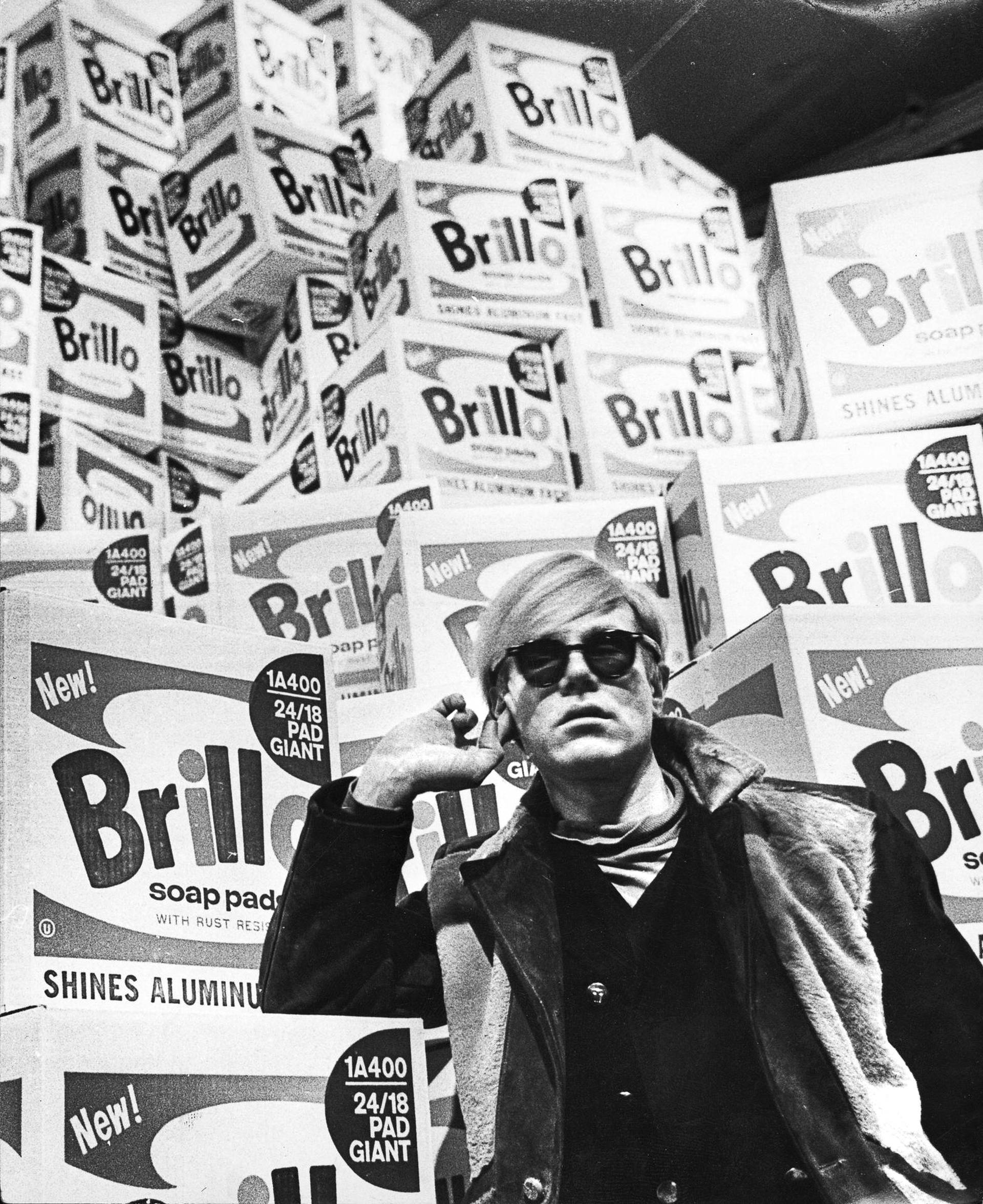

Andy Warhol surrounded by silk-screened Brillo Box sculptures, 1968. (Source: Lasse Olsson, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Not to forget two more connections between celebrity and death: Andy selected Elizabeth Taylor’s image for his portraits of her from a publicity still from the film Butterfield 8 (1960), a difficult period of the actress’s life when fan magazines had a field day speculating whether Taylor would even survive a serious case of pneumonia. Beyond that, recall that Warhol’s silver-soaked portraits of Elvis Presley depict “the King” pointing a gun in the direction of the viewer. And if you haven’t gotten the picture yet, Warhol’s meditations on mortality later included silk-screens of human skulls, the original “memento mori.”

That silk-screened revolver was also pointed at the artist. Warhol was prescient about rising levels of violence drenching the U.S., including the blood spilled in America’s name in Vietnam. He was not prescient about the prospect of being targeted by a real gun. A deranged acolyte shot the artist in 1968. Warhol survived the attack, but the damage changed him. Some say that this shocking event ended “The Sixties”; it certainly changed Andy’s approach to his scene.

On to the Next Phase – Andy Warhol, Professional Celebrity

When Warhol himself became a celebrity, celebrity became the theme of the remainder of his life’s work. He “performed” celebrity, and his sometimes obsequious-seeming portraits of the rich and often notorious, including Mao Tse-tung, are part of his exploration of the theme. These portraits, banal as they may seem, offer little miracles of surface interest when viewed in person. That Warhol, always obsessing over the surface of things!

Obviously, there’s a lot more of Andy’s life and career to tell. But what of Warhol’s legacy can we see in this early work? By forcing viewers to confront images outside the realm of good taste, Warhol enlarged the realm of what’s permissible in art at least as much as did his artistic progenitor, Dada eminence Marcel Duchamp.

Andy Warhol’s confrontational art, combined with his side hustles in music, performance, and film/video, changed our expectations of art to a large degree. In this extraordinary and critically acclaimed early period, he cracked wide the world, or at least a broad swath of American culture, and created enough open space for people – and subjects – at the fringes of acceptability to intermingle with others at the very center of the artistic and social whirl.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

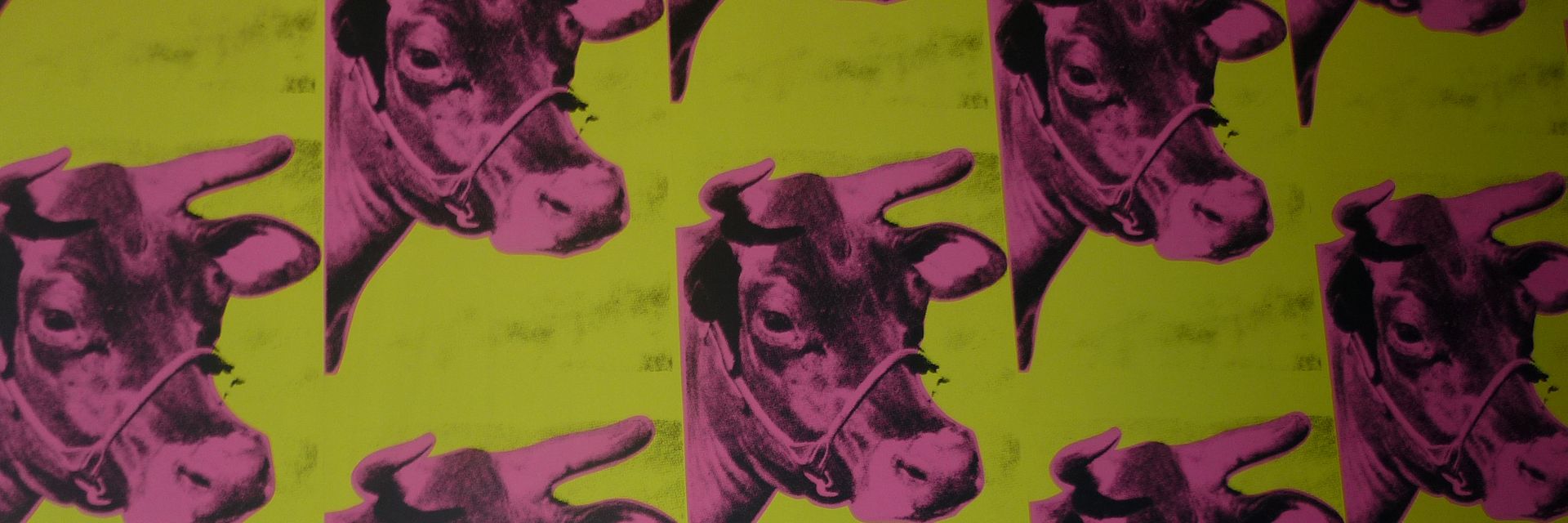

Title Image: Andy Warhol wallpaper, mounted in hallway of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh (Source: Photojunkie, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)