The first printing presses were invented around 600 C.E. by Chinese monks, and were further developed during the reign of the Tang Dynasty in China and in Korea and Japan. Eventually, the inventions made their way to Europe, where Johannes Gutenberg co-opted and developed the ancient model. He printed 180 copies of the Bible, thereby cementing his place in history. Ultimately, the printing press shaped modern communication as we know it, catalyzing everything from infrastructure and technology to universities and symphonies, and shaping most of the factors that define our modern era.

Before the advent of the Internet, before telephone wires and radio waves made it possible to instantly transmit information across the globe, before the days of newspapers and literature—and centuries before Johannes Gutenberg printed the first copies of the Bible—there was a Chinese peasant named Bi Sheng.

Most of the details of his life have been lost over time, but at some point in the 11th century, Bi Sheng was the first to develop moveable type—an innovation that streamlined the printing process, launched the widespread publication and distribution of Buddhist and Taoist texts, and eventually enabled Gutenberg to create his famous Bibles.

Though Bi Sheng might be the earliest innovator in the printing press business to whom we can put a name, he was not the first to develop printing technology. That distinction stretches much further back in time.

Ancient Origins of the Printing Press

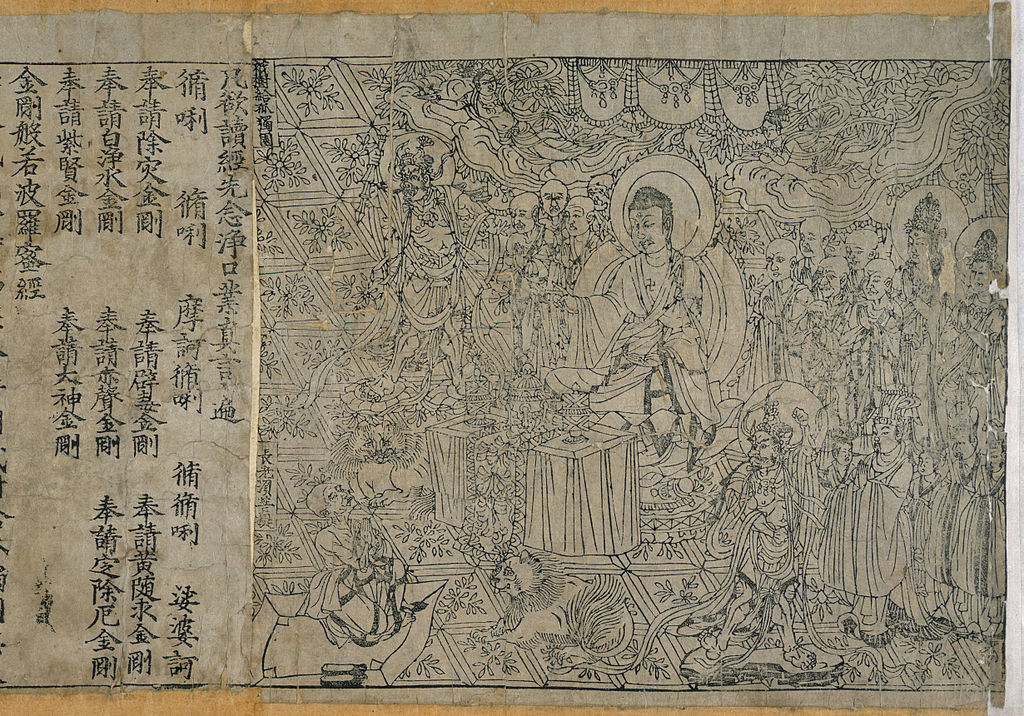

The earliest texts on record are believed to have been created by Chinese monks, around 600 C.E. The world’s first known printed text is a book of Buddhist scripture, the Diamond Sutra, which appeared in approximately 868 C.E. during the reign of the Tang Dynasty. The book—which remained sealed in a cave near Dunhuang, China for over 1,000 years before it was discovered in 1900—was created using a method called block printing. Similar methods were utilized in Korea and Japan during the same time period.

"As a lamp, a cataract, a star in space

an illusion, a dewdrop, a bubble

a dream, a cloud, a flash of lightning

view all created things like this."

—The Diamond Sutra

Over the next few hundred years, Chinese inventors produced other texts, manuals, and scrolls. Eventually, Bi Sheng came on the scene and created the first moveable clay text printing method. This involved carving letters into clay and baking them into hard blocks that could be pressed against an iron plate to create letters.

Frontispiece, Diamond Sutra from Cave 17, Dunhuang, ink on paper.

(Image courtesy of British Library's Online Gallery, via Wikimedia)

Finally, late in the 13th century, a magistrate of the Yuan Dynasty named Wang Chen created and mass-produced a series of books on agriculture called the Nung Shu, circa 1297, using moveable type, which allowed for great speed and mass production. Some of the books printed with Wang Chen’s processes actually made it to Europe. And, ironically, they detailed many other Chinese inventions that were later attributed to Europeans.

The first use of moveable metal type is believed to have been in Korea. The oldest surviving example of this advance is the Jikji Simche Yojeol, a Buddhist text printed in Cheongju during Korea's Goryeo Dynasty and dated to 1377.

The printing press—beginning with the earliest efforts of Chinese monks who painstakingly carved each character into metal—altered the DNA of human relationships and knowledge and sparked revolutions in countless dimensions of human life, the reverberations of which are still felt today.

Johannes Gutenberg Invents an Economical New Model

Though the earliest print technologies came from China, most of us associate the name Johannes Gutenberg with the invention of the printing press. Though he did not invent the device, his refinements made the printing press economically feasible for widespread European distribution of both written materials and presses themselves.

Gutenberg was born in Mainz, Germany, the third child of a patrician named Freile mum Gensfleisch and his second wife, Else Wirick zum Gutenberg. In his youth, he is believed to have tinkered in metalwork, and in his young adulthood he and his family were exiled from Mainz due to a conflict between the guilds and the patricians of the city. They moved to what is now Strasbourg, France, at some point between 1428 and 1430. Johannes worked in fields like gem cutting, crafting, and teaching, but around this time he also conceived a secret project that would change history. It all started with an idea that he is believed to have said came to him “like a ray of light.”

Peter Small demonstrating the use of the Gutenberg press at the International Printing Museum.

(Image courtesy of Vlasta2, via Wikimedia)

Little is known about the routines of Gutenberg’s daily life—it was the 1400s, after all—but one can imagine him toiling away in a cool, candlelit church basement in the wee hours of the morning, long after everyone else had gone to sleep, pulling his wires and metals into strange shapes and watching ink bleed onto parchment. Perhaps he sensed that he was altering the course of history, and could feel some strange force animating his fingertips; or maybe he was just in the fever of a midnight passion project. Regardless, what he would create would make it possible for billions of people to share and distribute their scientific revelations, musical scores, and literary endeavors—as well as details of their intimate lives—but at that time, what happened in solitude remained there.

Some of his business partners must have noticed the ink on his fingertips, or the bags under his eyes, or the strange hieroglyphs on his walls. Regardless of what gave his secret away, they insisted that he make them partners in his venture, whatever it might be. This was the beginning of complicated legal and monetary struggles that would haunt Gutenberg until his death.

Old Century, Same Money Problems

By 1448, Gutenberg’s invention was taking shape, but his financial life was in shambles. In order to finish his project, he needed to borrow money from Johannes Fust, who later joined him as a business partner in printing.

Frustrated by his lack of funds, Gutenberg decided to invest his energy in a new project in the meantime: making metal mirrors, which he and his partners believed could reflect holy light. His invention was never successful, but perhaps it did reveal a bit of wisdom from the beyond.

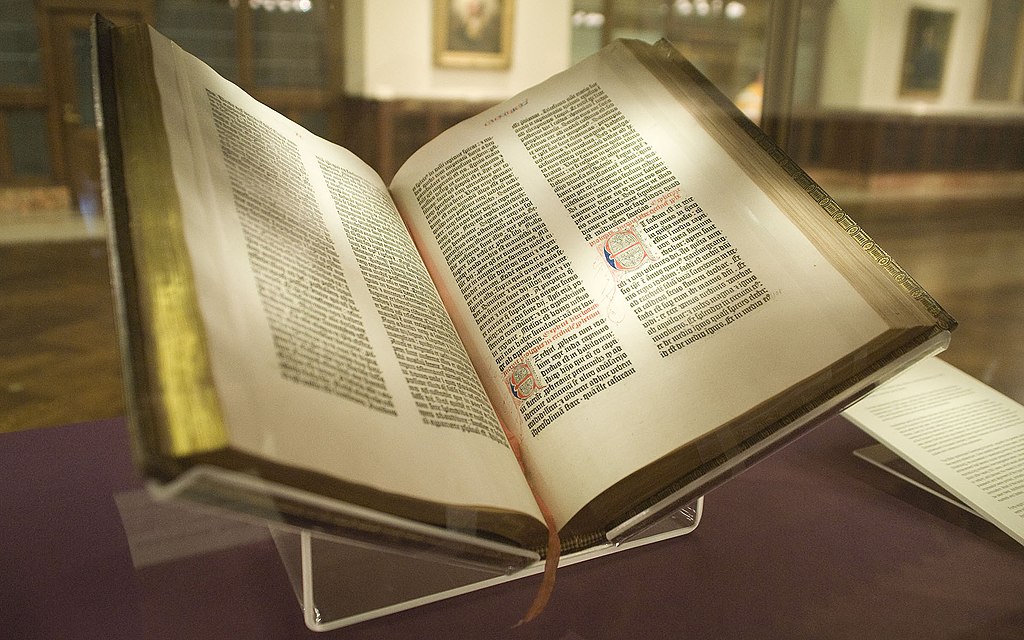

In 1452, he managed to finish the first and only book he himself would ever print: a Bible. He is believed to have printed 180 copies of the 1,300-page volume, an endeavor that required about 50,000 sheets of paper. At the time of their distribution, the Bibles were widely praised for the beautiful quality of their ink, which still remains a glossy black, even 550 years later.

Gutenberg Bible of the New York Public Library. Bought by James Lenox in 1847.

(Image courtesy of Kevin Eng, via Wikimedia)

Gutenberg sold some of them at the Frankfurt Book Fair that year. Today, only 49 copies are known to exist, and they are considered some of the world’s most valuable books.

"[The Bibles are] exceedingly clean and correct in their script, and without error, such as Your Excellency could read effortlessly without glasses."

– Pope Pius II to Cardinal Carvajal

Though Gutenberg’s invention was a smash hit, he never really had the chance to enjoy the fruits of his labor. By 1455, his business partner and investor Johannes Fust had turned on him, foreclosing on their shared business venture and, following a lawsuit, taking ownership of all of Gutenberg’s equipment. Gutenberg is believed to have continued printing, but by 1460 he had stopped entirely, possibly because of eyesight issues. The man whose invention would determine the course of history had lost almost everything.

His invention, however, would continue to grow in prominence. Peter Schoffer, one of Fust’s business partners who had acquired part of Gutenberg’s equipment in the lawsuit, continued to build on Gutenberg’s original model, eventually producing his own print copies of The Book of Psalms. Soon after, the printing press model began to spread like wildfire through Germany, eventually making it to Paris—and then taking the whole world by storm.

The Key to Success: Meticulous Attention to Detail

Though he is often given credit for the printing press, Gutenberg did not actually invent it. What he did was refine existing models of the printing press, making it more economical and feasible for widespread use.

(Image courtesy of Wikimedia)

Part of the reason his model was so successful was because of the care with which he crafted it. He made his own ink, designed to work well with metal, and he perfected a method of flattening paper by using a winepress. He also utilized a process called replica-casting, which involved creating brass outlines of letters and then filling them with a specially made, extra-durable type of molten lead.

"Printing presses in themselves provide no guarantee of an enlightened outcome. People, not machines, made the Renaissance. The printing that takes place in North Korea today, for instance, is nothing more than propaganda for a personality cult. What is important about printing presses is not the mechanism, but the authors."

—Jaron Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget

Ultimately, his innovative efforts slashed the cost of book production, making the process of printing written works far more economical than ever before. Still, the fact that he is largely credited with inventing the printing press is an undeniable example of European erasure of other societies’ contributions and inventions.

Impacts of the Printing Press: A Foundation for Cultural Overhauls

The issues surrounding proper credit for invention of the printing press notwithstanding, its worldwide influence cannot be understated. From the moment of its creation, it inspired fear, paranoia, and new forms of thought. Following its widespread distribution, members of the Catholic Church’s hierarchy grew worried about heresy and banned any book printed without their approval. Their fears were validated when revolutionaries like Martin Luther and John Calvin used print materials to create new forms of Christian worship.

Of its many benefits, the printing press enabled scientists to share their findings with others. Among them was Copernicus, whose On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres was classified as heresy by the church.

From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, from the advent of new technologies to democracy itself, the effect of the printing press has been indisputably vast and multifaceted. Since its inception, print media has been a mechanism through which radical new ideas are disseminated and individual stories and plights reach much wider audiences. It is no wonder that authoritarian governments suppress journalism, or that slave owners before the U.S. Civil War forbade their captives to become literate.

The printing press certainly changed the world, opening up space for the rapidfire dissemination of every kind of thought—good and evil, corrupt and revolutionary, unifying and divisive. Often cited as the greatest achievement of the first and second millennia, its existence forever altered communication, science, and the social world, redefining human relationships and—for better and for worse—shaping our society into what it is today.

Ω

Editor's Note, August 2021: A callout has been added to this article to highlight the first use of moveable metal type in Korea in the 14th century.

Title image: William Caxton showing printing specimens to King Edward, IV, courtesy of Wikimedia.