Ludwig van Beethoven’s music includes some of the most memorable, profound, and beautiful compositions of all time. But for much of his career he was unable to listen to what he had written. The effect of his gradual descent into deafness upon his music corresponded to the three generally accepted periods of his career (early, middle, and late) in revealing ways.

◊

“It was impossible for me to say to others: speak louder; shout! For I am deaf. Ah! Was it possible for me to proclaim a deficiency in that one sense which in my case ought to have been more perfect than in all others, which I had once possessed in greatest perfection, to a degree of perfection, indeed, which few of my profession have ever enjoyed?” – Ludwig van Beethoven, 1802, “Heilegenstadt Testament”

Early Signs of Deafness Send Beethoven into Crisis

In his 20s, Beethoven began experiencing issues with his hearing. The first symptom was tinnitus, a high-pitched droning sound that interferes with clarity and definition in hearing. By then, Beethoven was already well known as a composer and performer, and of course he continued to compose until his death at the age of 56. However, his career as a performer (he was a gifted pianist from a very young age) ended when the tinnitus overwhelmed his ability to hear his own playing, much less the other instruments onstage.

Beethoven’s gradually intensifying hearing problems, of course, were a source of great concern for him and figure prominently in the above-quoted “Heilegenstadt Testament,” a letter he wrote to his brothers in 1802. In that remarkable document, discovered among his papers after his death, he shares that his hearing loss sparked in him a life-and-death crisis, writing, “I would have ended my life – it was only my art that held me back.”

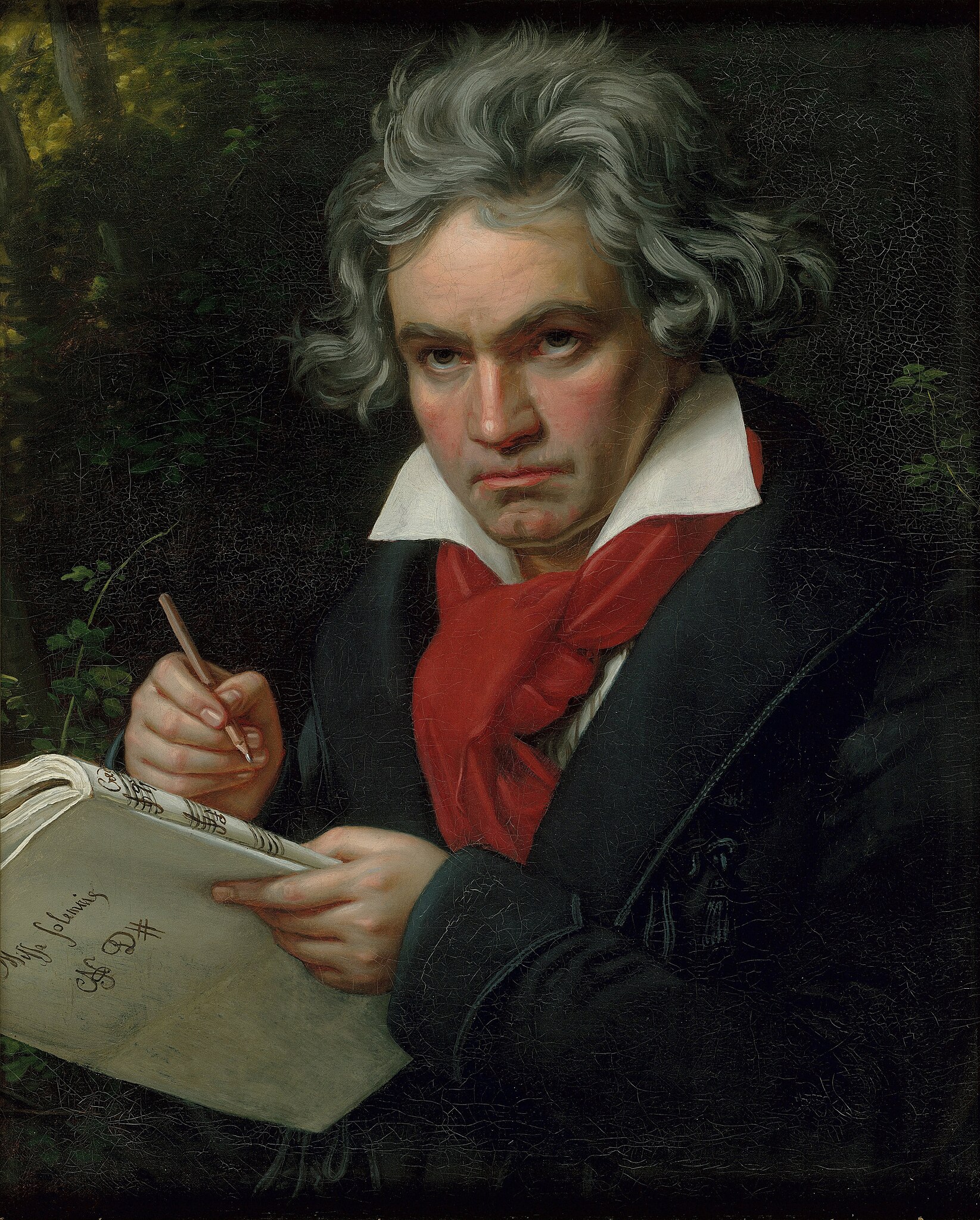

Painting of Ludwig van Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820 (Source: Beethoven House, Bonn, Germany, via Google Arts and Culture)

The maestro did continue, to the great benefit of audiences around the globe. In fact, not only did he continue, but his music changed, deepened, and became even more profound as he slipped ineluctably into his final years of profound deafness.

It’s generally accepted that Beethoven’s music can be divided into three eras, roughly. His early period begins with his first compositions in the 1780s and ends around 1801. His middle period runs through about 1814. And his final, or “mature” period concludes with his death in 1827.

According to the Beethoven “Digital Archive,” “Beethoven’s work comprises 722 larger and smaller compositions. They are registered as 138 works and groups of works with an opus number (op.) and 228 pieces without an opus number (WoO).”

Let’s explore how Beethoven’s hearing issues affected the three stages of his growth as an artist, and how he focused his considerable gifts to respond to the challenges posed by his gradual inability to hear normally the music he composed. We’ll examine each of these periods and explore how the slow but relentless progress of deafness may have influenced his approach to composition differently in each of the eras.

The Early Period: Glorious Music (and No Sign of Hearing Loss)

During Beethoven’s early years as a musician, when his hearing was not an issue, he was strongly influenced by Bach, Haydn, and Mozart, masters of the age whose work he found inspiring. In fact, he studied with Haydn and others, in Vienna, and several early works in a strong upper range were clearly indebted to Mozart.

The influence of Mozart and Haydn can be heard in the Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13, Pathétique. The composition is from 1798, when Beethoven was attempting to gain a foothold in Vienna, where he had relocated at the age of 21. Already, the young maestro was experimenting with big sounds and even bigger emotions.

Another striking piece from his early period is the Moonlight Sonata (Piano Sonata No. 14, Op. 27, No. 2). This lovely and deeply expressive piece shows the composer in a thoughtful and reflective mood, selecting notes in ranges not yet affected by his incipient tinnitus, and soft tones to express his musical feelings and ideas.

Watch the story of Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 14: Moonlight Sonata

The Middle Period: Sliding into Deafness (and How the Music Changed)

It has been said of Beethoven that he was fully deaf when he wrote all his great works, but that he was able to compose, perform, and even conduct his work without being able to hear a note.

This is a lovely myth, but it does not take into consideration the progressive nature of his hearing loss. The reality is that it’s quite possible to chart his slow but steady descent into total deafness through the periods of his career.

It was during Beethoven’s middle period, approximately 1801 to 1814, that the hearing problems became more apparent. He became acutely aware of the tinnitus and a gradual worsening of his hearing.

In these years, his music got louder, deeper, and grander – and, perhaps as a direct result, his star began to ascend as he captured strong emotions in his work. Representative work from this period would include the Symphony No. 3, Op. 55, Eroica, as well as the Piano Sonata No. 23, Op. 57, Appassionata.

The “middle period” is sometimes referred to as Beethoven’s “heroic” era, as the composer began to conceive many of his works on a grand scale.

In this period, Beethoven’s work to a large degree lost its brightness and high tones, which were supplanted by the more resonant tones of the deeper ranges that he could still hear despite that continuous ringing caused by the tinnitus.

Watch how Beethoven advanced the development of the piano through works like his Piano Sonata No. 23: Appassionata

Although, like Mozart, Beethoven was a man of the Enlightenment, these timeless classics linked him to the birth of the Romantic Era in music and art, in which an individual’s feelings became primary in aesthetic expression.

As Beethoven’s fame grew, he had the great fortune to have patrons compete over his services. As a result, he was in the enviable position of being a truly independent composer. For example, when he was offered a sizeable sum to take a position as a court composer in Italy, in 1809, a small group of his wealthy patrons banded together to support him with an annual grant of 4,000 florins (a grand sum at the time) to remain in Vienna. There he would be free to write whatever he wanted, on his own schedule, and not be wholly dependent upon commissions, occasional music, or a court appointment.

In 1811 Beethoven had to give up his lucrative career as a performer due to hearing loss. He did not appear onstage again until 1824, when he “conducted” – or, more properly, “directed” – the premiere of his Symphony No. 9 by giving cues to the conductor.

The Late Period: Profound Hearing Loss and More Profound Music

This masterful late period, from approximately 1815 to his death in 1827, corresponded with Beethoven’s final descent into complete deafness. By this time, he was using “conversation books” to communicate with those around him and was employing his prodigious gift for musical composition to create some of his most memorable, mysterious, and transcendent work.

The musical setting for his Catholic Mass, the Missa Solemnis, is a superb example. Beethoven called this the greatest work he had ever composed, and many would agree. Despite his total inability to hear, he nonetheless composed music of great complexity that presented technical challenges for virtuoso performers. The music is of great range, in tone, tempo, and timbre. It might be said that he vanquished his deafness as he pushed his inventiveness along with his mastery of composition to new heights.

The deepest and most acclaimed music of this period would be his chef-d’oeuvre, the grand Symphony No. 9, Op. 125. This massive work in four unforgettable movements famously incorporates a full chorus singing Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy,” which serves as the climax of the symphony – and, one might say, of Beethoven’s singular career.

Watch how Beethoven's grand Symphony No. 9 earned the admoration of contemporary audiences, yet Beethoven was unable to hear his aclaim.

Deafness and Death

Beethoven’s health steadily declined during his 50s. His hearing was gone, and he started to have physical symptoms of severe gastrointestinal distress that left him weak and bedridden.

From late 1826 he was quite ill, and doctors reached a point where they believed that all they could do had been done. His closest friends and a sister-in-law were present by his bed on March 26, 1827, as he breathed his final breaths. The actual cause of his death remains undetermined, but liver disease is the likeliest reason. The autopsy revealed a severe case of cirrhosis of the liver and some evidence of lead poisoning.

Cirrhosis, of course, is often associated with excessive drinking of alcohol, but the effect of lead has been a subject of speculation. It is possible that Beethoven was in the custom of drinking wine with lead as an additive (used as a fortifier), and equally possible that his doctors attempted to treat his illnesses, and possibly his deafness, with medicines containing lead.

What Survives: Beethoven’s Legacy (and His Deathless Art)

How do we sum up Beethoven’s life and art? It would be nearly impossible to exaggerate the profound influence he had on the evolution of music and the introduction of Romantic ideals into the cultural life of his time. To quote a recent biographical sketch:

Beethoven’s body of musical compositions stands with Shakespeare’s plays at the outer limits of human accomplishment. And the fact Beethoven composed his most beautiful and extraordinary music while deaf is an almost superhuman feat of creative genius.

We are indeed fortunate to have these masterpieces of cultural expression as part of the world’s heritage. To honor this heritage, think about selecting one of Beethoven’s “greatest hits” to enjoy.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Beethoven walk. (Credit: Julius Schmid, via Wikimedia Commons)