Milestone events in her life were orchestrated by her father and husbands, but Joséphine’s ever-evolving legacy keeps the discussion of her role in history alive.

◊

History is driven by fact, but remembered through stories. For the most part, historical periods can be drawn along a timeline, with spaced bullet points highlighting what is worth remembering and what can be forgotten. When telling a person’s history, however, you run into an issue: Life rarely plays out in a strictly linear way. At different moments in time they will have been motivated by different things, acted upon by forces beyond their control – and sometimes they might have just acted out of character.

How do you understand who a person from history actually was in isolation from the stories we tell about them? Well, you can’t.

Let’s consider a controversial historical figure known as Joséphine de Beauharnais. At her lowest point, she was impoverished and imprisoned, waiting for the guillotine. Just a few years later, she would be empress of France, traipsing around Versailles with a tiara perched on her head. Best known for being Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife, Joséphine has been envied for the power she had, revered for the gardens she curated, and disparaged for the role she played in bringing slavery back to the Caribbean. Joséphine’s is a complicated legacy that seems to take on a new form with every book written about her, every statue of her torn down, and every film made depicting her relationship with Napoleon.

Learn more about Joséphine's husband – and one of history's most infamous leaders – in Napoleon: Rise and Fall.

A Rose by Any Other Name

Marie-Josèphe-Rose Tascher de La Pagerie was born in 1763 on a plantation close to the town of Trois-Îlets on the Caribbean island of Martinique. The girl who would later be immortalized as Joséphine was neither given nor chose any of the names by which she is known today. Her upbringing on the island saw warm days and a relatively laid-back lifestyle compared to those of cosmopolitan Europeans. Her family hailed from noble origins, but their dreams of substantial wealth were wiped out by a hurricane that flattened the island’s infrastructure. Years down the road, Joséphine would use her power to restore Martinique to a bustling plantation economy fueled by slave labor.

Rose, or Yeyette, as she went by at the time, led a comfortable life through her teens. She was active in Martinique’s upper-class society, putting her education to occasional use but also developing an invincible confidence growing up in such a small, wild place. While afternoon jaunts through the tobacco fields were part of an almost idyllic daily routine, she likely knew that a change of circumstances was inevitable. For European women in the late 18th century, marriage was a transactional, strategic move to better the position of their birth families, and hopefully live with a richer one. Relocating, changing names, and having children wasn’t a consideration so much as an obligation.

Portrait of Empress Joséphine (Oil painting by Antoine-Jean Gros, 1809, via Wikimedia Commons)

By the time she was about 15 years old, Rose’s future was in the hands of Alexandre de Beauharnais, a Martinque-born military man living in France. While similar in age, Alexandre had fought in the American Revolution and established a political trajectory for himself while Rose was waiting to get married. She moved to Paris to marry him in 1779.

Some might have considered the high society of Paris more desirable than that of the Caribbean, but Rose found it challenging to adjust to the metropolitan bustle of Parisian life. As much as she tried to live up to expectations of being a worldly wife to an army officer, the teenager’s marriage didn’t work out. Her level of sophistication and intellectual curiosity was seen as “underwhelming” by Alexandre. Still, she had two children with him, Hortense and Eugène, before he separated from her in 1785.

The French Revolution: An Interlude of Terror

At 22, Rose was the mother of two, living in a foreign country with a husband who wanted to have nothing to do with her. Alexandre would raise their son Eugène while Rose would care for Hortense; this way, at least their son had a chance to learn the proper ways of being a Frenchman. For three years, Rose and Hortense lived in a convent in Paris. There, Rose mastered the soft skills that held her back from flourishing in her first stint in society. But learning how to be cultured and hold a fork the European way didn’t pay the bills.

Rose returned home to Martinique in 1788 when the financial pressures of raising her daughter mounted. The island to which she returned, however, was starkly different from the carefree paradise she knew as a child. Across the Caribbean, tensions were boiling over as enslaved people led revolts against provincial governments. Ideas like representation, democracy, and liberty inspired people around the world to take up arms for the prospect of self-government.

Rose likely thought she had dodged a bullet when she left France on the eve of the French Revolution. However, following a slave revolt on Martinique in 1790, she figured she would prefer to risk her life navigating the political minefield of Paris rather than being slaughtered on a sugar plantation.

Despite the political, social and economic unrest rattling the French, members of high society still had images to uphold and parties to host. Rose finagled her way onto the scene, putting her best foot forward, perhaps because she enjoyed socializing, but also because making friends in high places seemed to be a valuable survival tool.

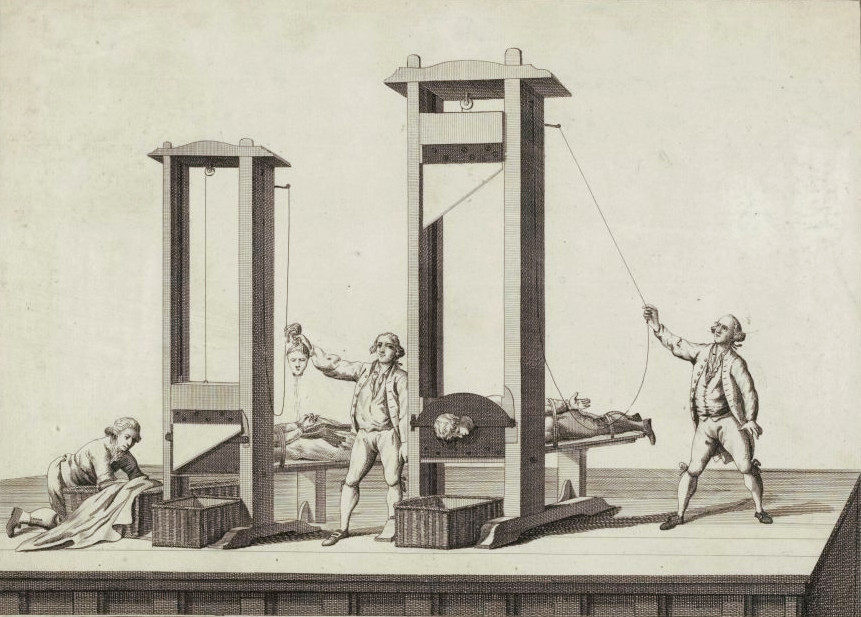

Print of a double guillotine (Source: Hulton Archive, via Wikimedia Commons)

Although socially separated, Rose and her husband Alexandre still shared the same married name. He had been serving in the Revolutionary army, and was tasked with defending the town of Mainz from foreign attacks. Unfortunately for him, Prussian forces overwhelmed his troops and seized the town. Shortly thereafter, the Jacobins imprisoned Alexandre for political plotting and thought it best to incarcerate Rose, too, if only because she was his wife. Alexandre lost his head to the guillotine, and Rose thought her fate would be the same. By luck, though, Rose dodged death when she was freed days before her scheduled execution thanks to a coup d’etat led by the moderates, which ended the Reign of Terror.

Napoleon’s Higher Love for Joséphine

In an even greater stroke of luck, one that would change the course of history, Rose caught the eye of an ambitious army officer, Napoleon Bonaparte, whom she impressed with her command of social events. What she lacked at 16, Rose had mastered at 33. Her aura of authority and overt femininity led Napoleon to see her as a gatekeeper to a higher status for himself. After he had been assigned to a military campaign in Italy, Napoleon and Rose wed in a civil ceremony. He had taken to calling her Joséphine, so Joséphine she became.

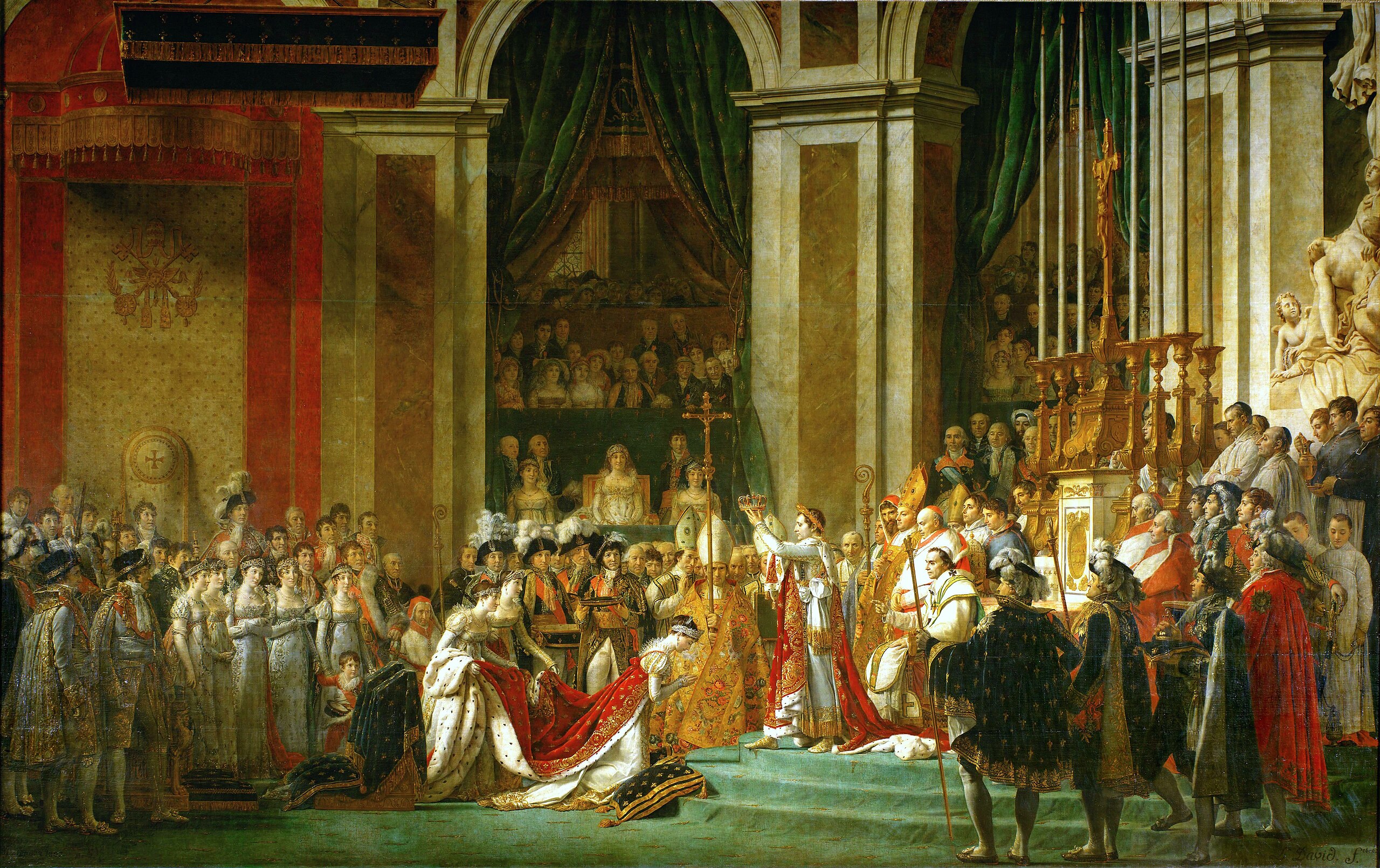

Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I (Painting by Jacques-Louis David, 1805-1807, via Wikimedia Commons)

Soon after they married, Napoleon left to fulfill his military duties – but this would be nothing like when Alexandre left her. Rather than leaving her destitute and alone, Napoleon bankrolled his new wife and saw to it that she lived comfortably. The two wrote letters to each other, pouring out their emotions for one another. The coyness in their early letters quickly morphed into blatantly sexual exchanges. Even when he suspected Joséphine of having an affair, Napoleon continued his barrage of love letters. Joséphine wrote less frequently than Napoleon, perhaps because she found his passion overwhelming or tiresome. Once the two were reunited, however, their relationship blossomed beyond platitudes.

Napoleon’s family was displeased by his marriage to Joséphine on account of her age and past marriage, not to mention that her cultural sophistication far exceeded their own.

Joséphine could have been a distraction to Napoleon on his military expeditions, but somehow their connection seemed to fuel his ambitions and confidence. A superstitious man, Napoleon believed that his life was guided by a “lucky star,” and Joséphine came to be a symbol of good fortune for him. Whether Napoleon’s success should be credited to the occult or a combination of ambition, good timing, and sheer tenacity, who knows? During his triumphs over the Habsburg Empire and in the War of the Second Coalition, Napoleon was riding high militarily, politically, and personally with Joséphine by his side. The confluence of France’s unrest and Napoleon’s success enabled him to seize power and become emperor in 1804.

Joséphine: The Empress Who Impressed

As empress, Joséphine set out to leave a lasting mark on French culture. She actually spent more on fashion than her predecessor, Marie Antoinette, spurring increased demand for French-manufactured cotton when her husband banned the British from trading in any of his empire’s countries or colonies. Her personal contribution included purchasing as many as 900 dresses annually, along with 1,000 pairs of gloves, in an effort to revive not only the economy but to restore the pomp of high society in the wake of the French Revolution.

Even in the grips of extreme financial strain, Joséphine always had bouquets of flowers in her home, calling them a “necessity of life.” Once Napoleon became emperor, Joséphine cultivated a massive garden with plants from all over Europe, Egypt, Australia and South America.

Napoleon’s dictatorship undermined the ideals of the revolution that had enabled him to seize power. He reinstated an aristocracy, which fed into the ostentatious court ceremonies he and Joséphine presided over. This is where Joséphine came into her own, proving to be more than just an Emperor’s arm piece. Thanks to her long-established connections from the old order of high society, Joséphine orchestrated the reintegration of ousted aristocrats back into Napoleon’s court. Her puppeteering returned power to politicians and socialites, who gratefully resumed their coveted roles in society.

An Allegory of Empress Joséphine as Patroness of the Gardens at Malmaison (Credit: Baron François Gérard, c. 1805-06, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons)

Beyond this, Joséphine played an integral role in Napoleon’s brand management. She commissioned domineering portraits of her husband and amassed a collection of botanical illustrations to record the variety of plants she cultivated in her gardens. Day in and out, Joséphine worked to create lasting symbols of her husband’s political, cultural, and social power in his home country, while also indulging in her own passions. In addition, she was the subject of many portraits, indulging a self-interest in solidifying her own place in the history of France.

Immortalized Off the Throne

Napoleon and Joséphine did not stay married, as Joséphine (due to infertility following the birth of her second child) was unable to provide him with the one thing he most needed: a son. In 1809, Napoleon arranged for their marriage to be annulled, allowing Napoleon to remarry, this time to someone who could produce an heir. Joséphine was replaced by an Austrian nineteen-year-old, Marie-Louise. Most of the imperial palaces were redesigned, and traces of the empress who could bear no more children faded.

Joséphine’s second child Hortense married Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Louis, thus becoming both Napoleon’s step-daughter and sister-in-law. Hortense’s son would later become emperor of France, as Napoleon III. So, Joséphine did, in a roundabout way, spawn an heir to Napoleon’s throne.

Joséphine continued to live at Malmaison, a stately home she had purchased while married to Napoleon. There she continued with her patronage of the arts and love of gardening. She died only a few years after separating from Napoleon, but his love for her lived on for a while longer. Though historical accounts differ, it is rumored that Napoleon’s last words from his deathbed in exile were a laundry list of what he most valued: “La France, l’armée, tête d’armée, Joséphine…”

Statue of Empress Joséphine in Fort-de-France, Martinique (Credit: Gregor Julien Straub, via Wikimedia Commons)

Statue of Empress Joséphine in Fort-de-France, Martinique (Credit: Gregor Julien Straub, via Wikimedia Commons)

Two hundred years after she died, Joséphine continues to capture attention. She is credited in many museums for the art she commissioned and preserved, her statue stands on her home island of Martinique, and her love story with Napoleon inspires feature films and historical fiction to this day. How her story has been written in history books has changed over the years: Sometimes she is presented as an unassuming girl who won the social lottery; other times she is seen as a calculating conductor of an imperial society.

Joséphine’s image today is largely determined by how it is presented in a particular moment. However we see her – whether as a character written through emotional stories or an icon of deplorable politics – Joséphine’s name permeates discussions of influence, celebrity, and chance. By whatever name, Rose Tascher de La Pagerie, or Joséphine de Beauharnais, or Empress Joséphine of France was a woman who leveraged her circumstances and took advantage of serendipitous encounters to cement an enduring legacy.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV and freelancer. Originally from Georgia, she went to college to study philosophy and studio art. She now works in Chicago as a media relations coordinator.

Title image: statue of Joséphine de Beauharnais by Gabriel-Vital Dubray on the grounds of Malmaison (Credit: Photo by Moonik, via Wikimedia Commons)