When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BCE, the fate of the Roman Republic had already been sealed. In fact, the foundations of Rome’s unique representative government had been crumbling for more than 50 years before Caesar’s river excursion. Rome was wracked by class differences and violent political struggles in which long held rules were shattered. Caesar had only to look to the recent past at two Roman generals, Marius and Sulla, for case studies into achieving power and sole rule over Rome.

◊

Classical Rome is a wonderful petri dish for observing ancient authoritarians in an optimal environment. The dysfunctional Roman culture valued fame, glory (war victories), and wealth above all else – and then set ambitious nobles against each other through winner-take-all contests in a pattern not unlike our own politics. Ruthless quests for power, when tempered by a common good, had propelled Rome to the heights. But it also led to mass destruction, slaughter, and plunder on a scale not seen before.

As Sallust, an historian and confidante of Caesar noted, “Warmonger against every nation, people, and king under the sun, the Romans had only one abiding motive – greed, deep-seated, for empire and riches.”

By the time of Gaius Julius Caesar’s rise in the first century BCE, governmental checks on the Roman elite had been in long decline. Caesar did not break norms when he crossed the Rubicon in 49 BCE and marched to Rome with his army to ultimately become dictator for life; he merely followed a path that had been blazed by others. Considering that his predecessors had done most of the work of wrecking the Roman constitution, the rise of this populist megalomaniacal leader was almost inevitable.

Caesar’s World

For a role model and guide, Caesar had only to choose the hyper-ambitious general Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Sulla, a handsome playboy, was blessed with “good genes” as a self-claimed descendent of Venus. Fueled by a burning desire to outdo his rival, the wealthier and more famous Gaius Marius, Sulla made his bones smashing uppity Roman allies during the Social Wars (91–88 BCE).

Two Roman soldiers shown in the Ahenobarbus relief (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 88 BCE, Sulla was initially given the ultimate prize, command against the meddling eastern ruler and constant thorn in Rome’s side, Mithridates. It was an honor that Sulla saw as a path to even greater glory and power. He then watched as his prize was taken away through the political dealings of Marius. Not one to accept the rules when they went against him, Sulla embarked on the unthinkable: He massed his six legions (35,000 soldiers), hardened from battles on the Italian peninsula during the Social Wars, and headed for Rome to “free her from tyrants,” that is, from Marius and his followers.

By law, no army could enter Rome: After all, it was the sacred ground of the gods! But as a god-like person, Sulla surely felt that the rules didn’t apply. With his army encamped in town, Sulla hunted down his enemies, had Marius declared an enemy of the state, and forced the Senate to grant him the honor of leading an army against Mithridates. Sulla had effectively “crossed his Rubicon,” more than 40 years before Caesar’s famous fording of the river.

After having received promises from the Senate not to interfere with his legislative “reforms,” he left to do battle with the eastern monarch in Pontus, now northern Turkey.

The Roman Republic: A Government of Some of the People

While Sulla is away in the east, we’re at a good point to take a closer look at the Roman government. Unique in the ancient world, Rome had a republic – from res publica, the “people’s thing”– that had lasted four hundred years. Power was rotated among the elite noble families through two consul positions, making it a government with dual prime ministers. The consuls each held a term of one year and were essentially selected by the Roman Senate, allowing ambitious Romans to have their chance running the important things – foreign affairs, war, taxes. The sharing of the consulship was an innovative way to massage the egos of the egomaniacal Roman elite.

Those of non-noble blood, the plebeians, were represented by an assembly, presided over by tribunes, which passed most of the Roman civil laws. These grants of power to the plebeian class were begrudgingly made earlier in the history of the Republic as an acknowledgment that the people – the 99% who were fighting and dying for Roman glory – deserved at least some voice.

The aforementioned Social Wars brought to a head the differences between the classes, each represented by their separate political factions – the populares (“favoring the people”), and the aristocratic optimates (“the best ones”). The war was fought over whether to extend citizenship to Rome’s neighboring allies (or socci). Sulla, as a member of the optimates, was against enlarging the vote. He feared Marius, a leading populares, would exploit loyalties gained through enfranchisement (and land redistribution) that would supersede obligations to the Republic. It was a well-founded fear, as Caesar would soon prove.

Sulla as a Roman Proto-Caesar

Back to Sulla. In 82 BCE, after settling with Mithridates, Sulla once again returned to Rome with his legions. He found a city where the populares faction had broken their promise and rescinded some of his reforms that were intended to make it more difficult for populists to thrive.

Now unstoppable, he convened the Senate, declared himself dictator, a temporary position that the Roman constitution allowed for in times of distress. Sulla, though, stayed as dictator for an unprecedented three years. He sought bloody retribution against Marius’s followers, brazenly posting a long list of names in the Forum of those to be executed. During this time he continued to weaken the power of the tribunes and the plebeian assembly, required consuls to first serve as lower magistrates, and diluted the Senate by adding more positions for his loyalists.

Sulla’s soldier refuses to kill Marius after his capture. Painting by Jean-Germain Drouais, 1786 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Sulla’s governmental reorganization was aimed at preserving the existing oligarchical nature of the Republic and preventing power-hungry populists (from the upper classes) from gaining control. But in restoring the status quo, he left the constitution in tatters and set a norm-breaking template for Caesar to follow.

Young Caesar:Sharp Dressed Man

Born in 100 BCE, Gaius Julius Caesar descended from a long line of Julius Caesars that pop up in Roman history. His prominent father, Gaius Julius Caesar III, was a governor in Asia, and his sister Julia was married to Marius. At the time of Sulla’s dictatorship, connections to Marius were most certainly not a benefit!

The independent Gaius Julius Caesar IV eventually drew Sulla’s wrath by not following the dictator’s order to divorce his teenage wife Cornelia, who herself was the daughter of a prominent populares. Caesar wisely self-exiled to Asia, but later received a reprieve through the influence of his powerful mother, who had deep connections to Sulla and his faction.

In 78 BCE, after the death of Sulla, Caesar, now only 22, returned to Rome and embarked on his political career. According to Plutarch, the great historian of this period, he was known as a sharp dresser and had a talent for being liked. The shape-shifting patrician Caesar set out to be leader in the populares faction. He was also riding a wave of resentment against Sulla and the optimates, and particularly against Sulla’s laws restricting the tribunes, laws that were finally repealed later in that decade.

“Where is honour without moral good? And is it good to have an army without public authority, to seize Roman towns by way of opening the road to the mother city, to plan debt cancellations, recall of exiles, and a hundred other villainies ‘all for that first of deities, Sole Power?’” —Cicero, commenting on Caesar, 49 BCE

Just as money is crucial in our own politics, young Caesar also needed lots of denari. He borrowed heavily, and in 65 BCE he was elected as an aedile, essentially a low-level bureaucratic position in charge of maintaining Rome’s sprawling infrastructure of temples and aqueducts. But it was a first step to gaining followers among the plebeians, and he was known for putting on lavish games to attract attention. In today’s world, he would be a young, on-the-make parks commissioner with a reputation for producing popular outdoor concerts.

The New Normal: Conspiracies and Dictators

The careful Caesar may even have been involved in (or was at least aware of) the audacious Cataline Conspiracy, which was a plot by yet another young upstart, Lucius Sirgius Cataline. The plan was to overthrow the existing order, institute land redistribution, and, interestingly, to cancel all debt both for the impoverished and wealthy. Similar to Caesar, Catalina was ambitious, debt ridden, and a populist leader from patrician stock. In fact, Caesar had supported Cataline’s bid for consulship against the great orator Cicero in 64 BCE.

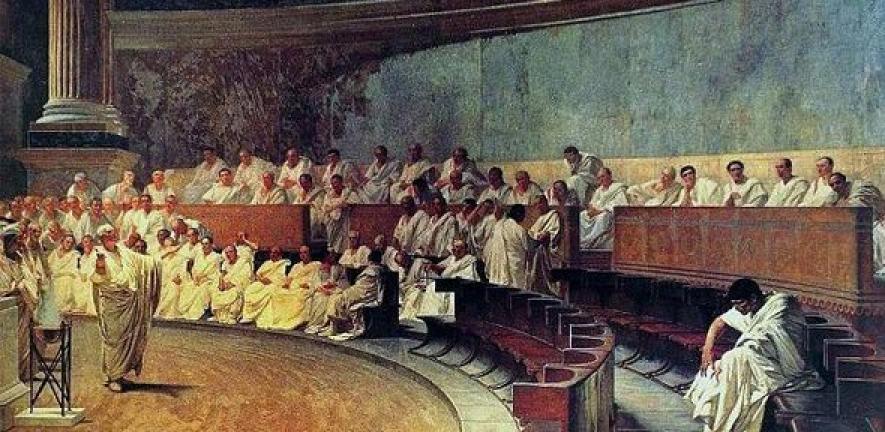

Cicero denounces Cataline in the Roman Senate. Painting by Cesare Maccari (Source: University of Cambridge)

With the Cataline Conspiracy, yet another norm was broken. The idea that the oligarchy needed to be replaced and run by a single person had been released into Roman politics. The wily Caesar was carefully watching from the sidelines.

Conventional politics were now dead, and a revolution was in the making. It was only a matter of time before a combination of dark forces would coalesce and take control. Before Caesar became famous as a general committing genocide in Gaul, there was the great Pompey. Conqueror of hundreds of lesser nations, Pompey sought to become consul in 59 BCE. He would not be slowed down by Sullan reforms, which would have required him to first serve in lower government positions, and so he started making public his bid for power.

The Senate was fearful that, like Sulla, Pompey would march his army to Rome. Gaius Julius Caesar IV then stepped in and, through a series of maneuvers, became an acceptable candidate for consul while also agreeing to Pompey’s request to distribute land to the veterans of his campaigns.

Pompey and Caesar formed two legs of the so-called First Triumvirate, with the third provided by Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the wealthiest men in Rome. Crassus’s fortune was made in the brass-knuckled world of Roman real-estate, having bought distressed property taken from the unfortunate victims of Sulla’s purges. He’s better known to us today as the general who put down the Spartacus revolt.

Caesar’s co-counsel, Marcus Bibulus, who represented the optimates, ultimately fled in fear, and Julius Caesar ruled as sole consul with support of Crassus, which literally means crude in Latin, and Pompey, known affectionately as the teenage butcher.

What a threesome!

The Roman Republic Wasn’t Destroyed in a Day

From here it’s a short trip to the Caesar that we know. In 58 BCE, he was appointed governor of Gaul and started his war against Celic and German tribes – a war that had not been officially approved by the Senate. Gaul was a wealth-making opportunity for Caesar, as the plunder and confiscation of treasuries would pay off his debts and finance the rest of his rise. Plutarch reported that a million Gauls died during the eight-year campaign. But for Caesar, the slaughter was a small price to pay.

Roman coin with image of Caesar (left), Venus and Aeneas (right) (Credit: CNG, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, Caesar’s own puffed up but highly readable account of those years, acted as powerful political propaganda that enhanced his image and myth over that of Crassus and Pompey. In 49 BCE, alarmed by Gaius Julius Caesar IV’s fame and the unusual loyalty of his soldiers, the Roman Senate asked him to give up the command of his Gallic legions.

As we know, he refused. And the rest is history.

Ω

Title Image: Statue of Julius Caesar. The Louvre, Paris (Source: Pixabay)