During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a geopolitical cage match. From the Berlin Airlift to the Cuban Missile Crisis – not to mention two hot wars in Korea and Vietnam – the stakes couldn’t have been higher. One nearly forgotten episode, though, may have taken the cake for a combination of audacity and, at the same time, deep secrecy and Cold War paranoia: the attempt by the U.S. to retrieve a sunken Soviet submarine from the depths of the Pacific Ocean. Here’s a look at the nearly successful mission to steal that stricken vessel, the K-129.

◊

In MagellanTV’s exciting, Russian-produced movie Salyut-7, set in 1985, two intrepid cosmonauts travel to a crippled Soviet space station in a desperate attempt to bring it under control – and to prevent the U.S. from plucking it out of orbit with the Challenger space shuttle.

Before you conclude that KGB intelligence officers must have been drinking way too much Cold War vodka, consider this: Some years earlier, the CIA, working with reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, attempted a similar secret mission – but right here on Earth.

The Soviets’ K-129 submarine had sunk and was lying three miles below the surface of the Pacific Ocean. The Soviets wanted it back but couldn’t get to it. The CIA could get to it but didn’t want the Soviets to know. And Hughes provided a perfect cover story.

Cold War Tragedy in the Deep Waters of the Pacific

One day in 1968, disaster struck the K-129, a nuclear missile-carrying submarine of the Soviet Navy. One moment all was well aboard the sub and the next, some sort of catastrophic accident occurred. All 98 crew members perished.

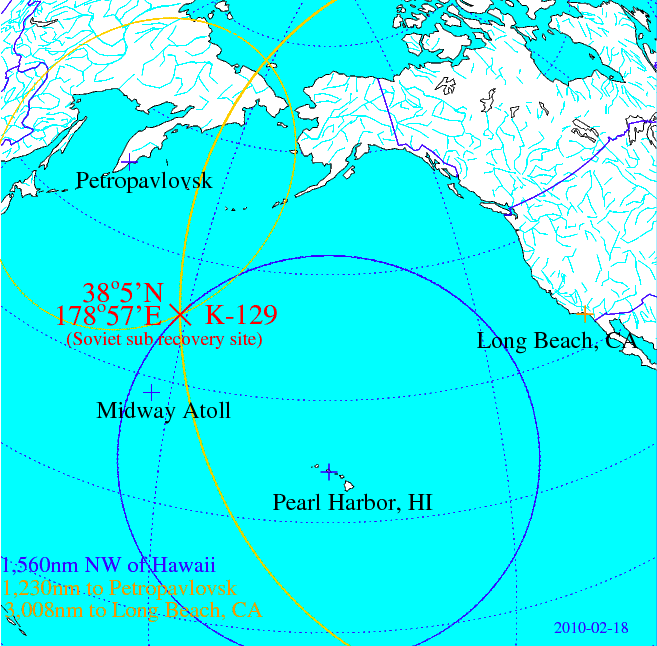

K-129 submarine recovery site (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

At first, the Soviets believed that their sub had collided with a U.S. Navy submarine in the area. There was no truth to the theory, but hey, it was the Cold War, and each side tended to think the worst of the other in such situations. But at least, the Soviets reasoned, with K-129 resting on the ocean floor more than 16,000 feet down, there was no way the Americans could get to it to steal its secrets. As it turned out, they were wrong about that, too.

Project Azorian is Born

Using data provided by the U.S. Navy and Air Force, the CIA was able to locate the stricken submarine, and an American sub, the Halibut, was able to deploy a sledge equipped with cameras to photograph the virtually intact K-129. Taking pictures was nice, but the CIA wanted the sub’s secrets – and raising it was beyond their capabilities at the time.

Enter the legendary – and possibly quite bonkers – Howard Hughes. He had had extensive involvement with U.S. defense interests over the course of his career, and the CIA approached him with an audacious proposal: to build a ship capable of lifting a 2,000-ton submarine from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. They would call the effort Project Azorian.

The Best-Laid Plans

Six years and $350 million later, a unique vessel called the Glomar Explorer floated three miles above K-129. Amazingly, despite observation by Soviet surface vessels and helicopters, the cover story that the CIA and Hughes concocted had held: Hughes publicly claimed his ship was collecting magnesium nodules from the seafloor. In fact, though, the Glomar Explorer had been equipped with a gigantic claw-like device that was designed for one purpose only: to grasp the submarine and bring it to the surface. And it almost worked.

.jpg)

USNS Glomar Explorer (Source: U.S. Government, via Wikimedia Commons)

At first, all went well. The claw was attached, and the lifting of K-129, which was about 300 feet long, proceeded very slowly. Suddenly, when the sub was still about two miles below the surface, the Glomar Explorer shuddered – and all but a 40-foot section of K-129’s hull fell back to the bottom.

Oops!

Won’t Get Fooled Again

Years later, in 1985, Soviet officials trying to decide what to do about their crippled Salyut-7 space station might very well have been reviewing their files on Project Azorian. To them, the idea of the U.S. mounting a secret mission to abscond with their space station could have seemed plausible.

In reality, the Challenger mission probably wasn’t seriously considered, but one can imagine the bigwigs in the Kremlin thinking about the old adage: Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me. And they weren’t going to get fooled again.

Ω

Arthur M. Marx is Articles Editor for MagellanTV. He was previously a senior writer/editor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. He lives in Sarasota, Florida.

Title image: An aerial starboard bow view of a Soviet Golf II class ballistic missile submarine underway via Wikimedia Commons.