Political passions erupted in 1968 as the Chicago Democratic National Convention sparked violent outbursts both outside and inside.

◊

In the watershed year of 1968, the U.S. was deeply divided over the Vietnam War, civil rights, and a host of other issues. The assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy in the spring had further traumatized the nation. Against this backdrop, the Democratic Party convened in August to nominate its presidential candidate, with Vice President Hubert Humphrey having emerged as the front-runner in the wake of President Lyndon B. Johnson's withdrawal from the race.

Inside Chicago’s International Amphitheater, the Democratic Party was in disarray. Humphrey, who supported President Johnson’s Vietnam policies, faced significant opposition from anti-war factions led by senators Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern. The fights within the convention made the tension palpable. As NPR reported, “By the third and fourth nights, these fights included incidents of pushing and shoving. Punches were thrown.”

Dive deeper into the pivotal year of 1968 in this engrossing documentary.

The Yippies Turn Up the Heat and the Chicago Police Crack Down

Outside the convention, the streets of Chicago became a battleground. The Youth International Party, known as the Yippies, descended on the city with thousands of young people to lead raucous protests. The Yippies were known for theatrics and provocation, including the nomination of a pig – named Pigasus – for president. Their presence was seen as a direct challenge to the Democratic Party and the city of Chicago.

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley was determined to maintain order. Known for his authoritarian style, he deployed thousands of police officers (backed by thousands more Illinois National Guard troops) to confront the protesters. His directive was clear: There would be no disruption of the convention. The Chicago Police Department, following Daley’s orders, employed aggressive, heavy-handed tactics.

On August 28, what began as a peaceful march to the convention turned into a violent clash. Television cameras captured the brutality of the police as they beat and arrested protesters. This “police riot,” as it was termed by the U.S. National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, shocked the nation and further polarized public opinion.

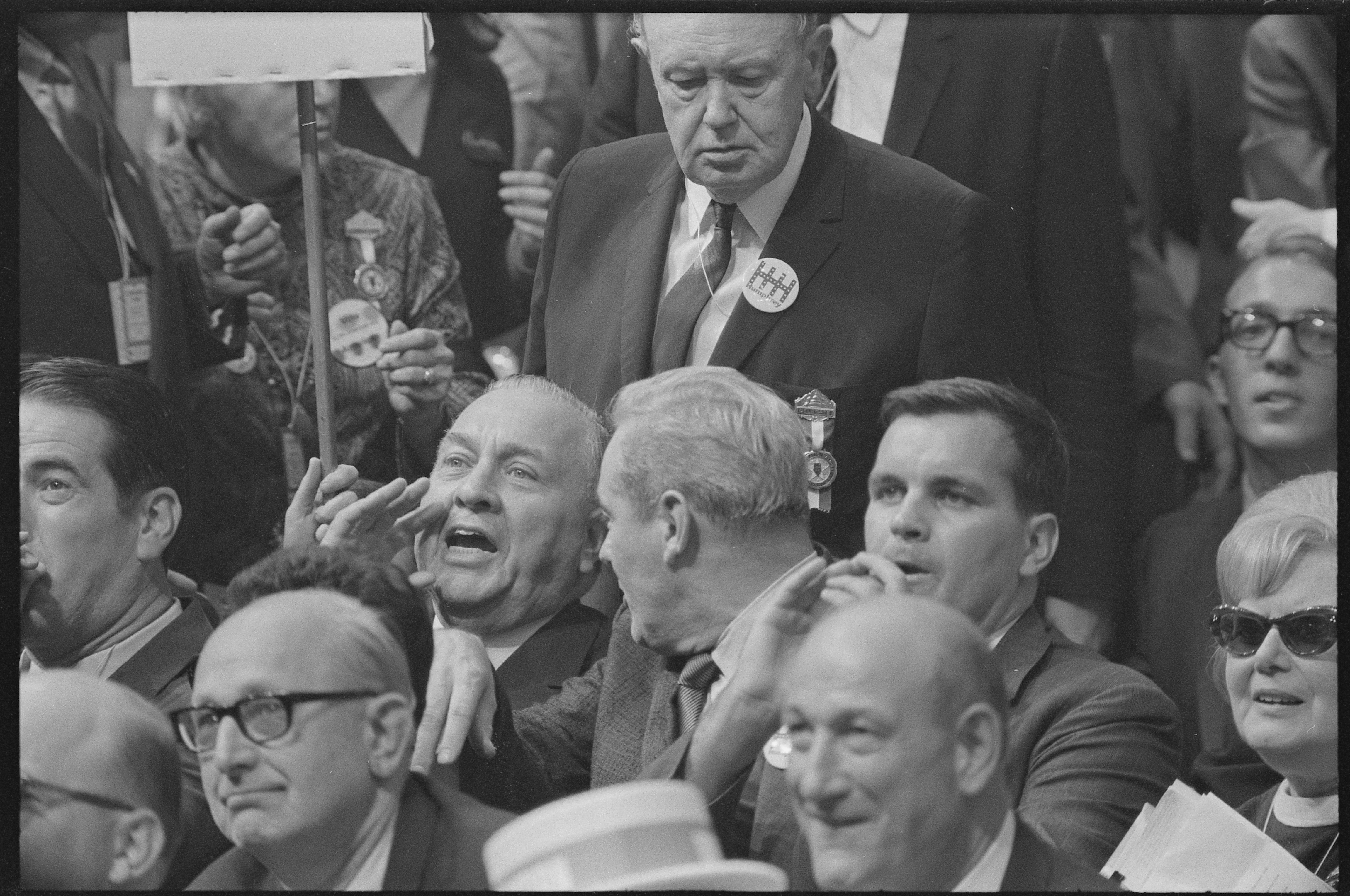

Richard Daley (hand to mouth) jeers a speaker at the convention who was criticizing the Chicago Police Department’s actions. (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

Richard Daley (hand to mouth) jeers a speaker at the convention who was criticizing the Chicago Police Department’s actions. (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

During this violent police action, Daley was assailed inside the convention hall by outraged reporters, some of whom had been caught in the riot. Questioned about the police behavior, Daley memorably replied, “The policeman is not here to create disorder. The policeman is here to preserve disorder.” It was a quote – a Freudian slip? – that echoed ominously across the nation. The blood in Chicago’s streets became the story of the week. Hubert Humphrey secured the nomination, but the televised images of chaos and brutality dealt a severe blow to his campaign.

A Wounded Humphrey Is Trounced by Richard Nixon

These shocking events left the Democratic Party in shambles. Humphrey ran on a deeply unpopular centrist platform. His Republican opponent, Richard Nixon, ran on a law-and-order platform and his “secret plan” to end the Vietnam War. Nixon won by a huge margin in the Electoral College, with 301 electoral votes against Humphrey’s 191. He likely would have won by more had segregationist George Wallace not mounted a third-party campaign that garnered 46 electoral votes.

America was in psychic pain, having lived through a display of naked authoritarian force the likes of which hadn’t erupted in the U.S. for more than half a century. Nixon had won, but in fact, he had no plan, secret or otherwise, to end the war. He actually escalated the war and left Americans battle-weary and shell-shocked by the war in Southeast Asia and in America’s heartland. It was a wound that was slow to heal.

Ω

Title Image: Police confront protesters in Chicago’s Grant Park, August 1968. (Source: National Archives at Chicago, via Wikimedia Commons)

.jpg)

.jpg)