Many animals were revered in ancient Egypt, but none was as sacred as the bull-god, Apis, the divine earthly intercessor for Egypt’s god of life, Ptah.

◊

To archaeologists, finding a representation of an animal in a mummified Egyptian’s burial chamber is no surprise. In fact, hundreds – if not thousands – of mummified cats have been found accompanying the dead of ancient Egypt to the afterlife. Comfort was important to the posthumous life of the soul, and keeping your cat by your side was a common custom.

Many other animals, often appearing in semi-human form, were part of the divine order, as represented in carvings and drawings. Anubis, god of the afterlife, was represented with the head of a jackal; Horus, god of protection, with a falcon; Thoth, god of wisdom, with an ibis; Sekhmet, goddess of war, with a lion; and Sobek, god of fertility, with a crocodile.

You may be wondering why ancient Egyptians depicted most of their gods with animal heads. Good question. With their strong connection to the natural world, Egyptians believed that certain animals embodied specific qualities and powers. By giving a god an animal head, they were visually representing the god’s particular characteristics and abilities.

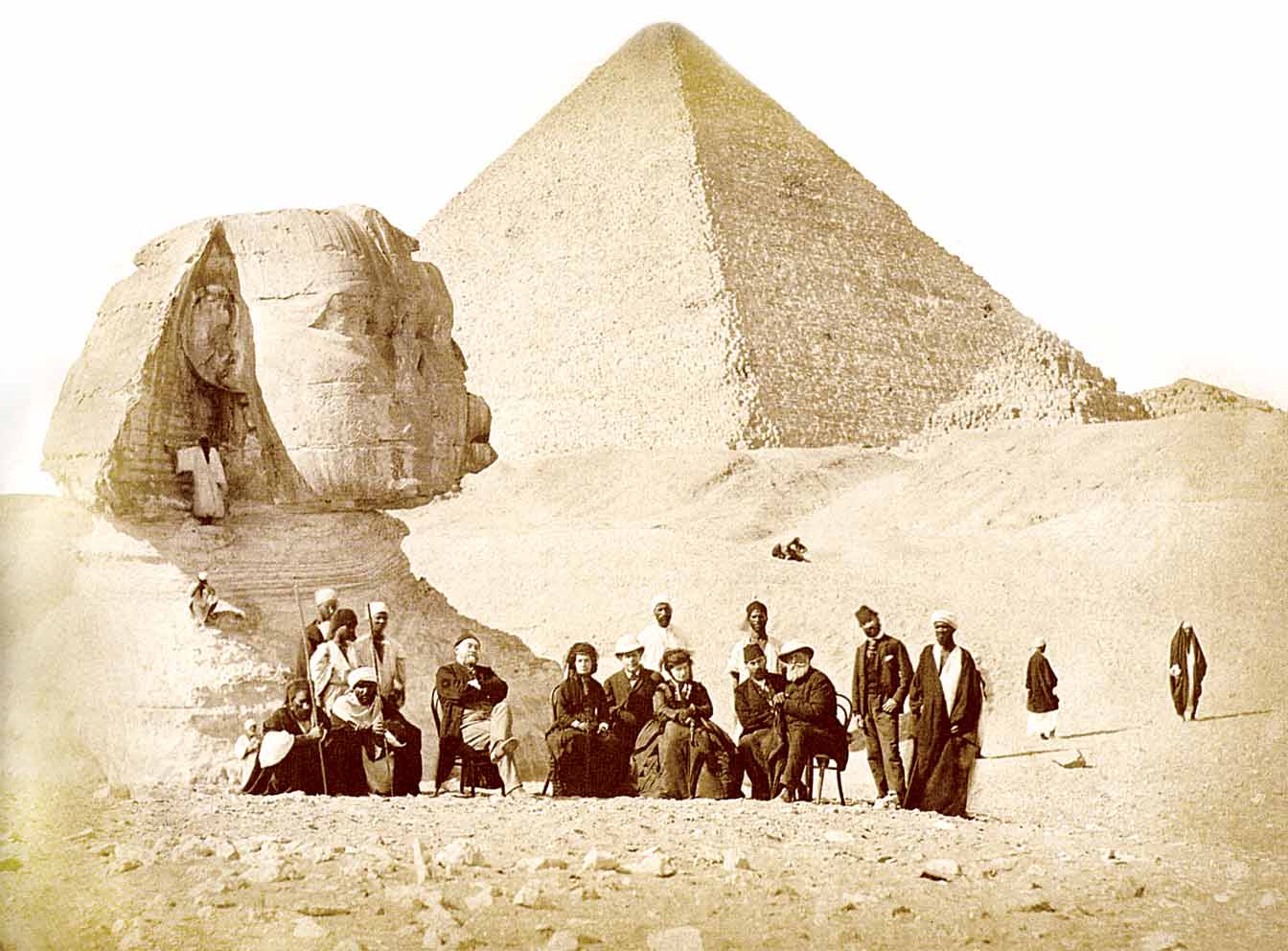

However, the discovery of mummified bulls with their own burial chambers reveals a god of a different order. In 1851, French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette was the first to uncover a vast necropolis close to the Egyptian village of Saqqara. Unexpectedly, it held a catacomb filled with scores of mummified bulls in huge sarcophagi carved of stone. This revealed a custom prevalent for many centuries: A specially selected bull, given the name Apis, was venerated as the divine representative of the god of the life-force, Ptah. The custom lasted well over 1,200 years, from the New Kingdom (approx. 1570 BCE) through to the Ptolemaic Period (approx. 330 BCE).

Dig deep into the archaeological excavation that unearthed Apis, the bull-god, in this revealing MagellanTV documentary.

Rather than just a bull-headed human, this god was represented by a full-bodied bull carrying between his horns a disc encircled with a cobra, representing the Sun as well as creation and kingship, domains of the god Ra. In life, this bull lived with great refinement compared to other bulls. Once he died of natural causes, he was replaced by another living bull to assume the same responsibilities.

How did this custom come to be? What was its meaning and significance? Come along on a journey to learn how Apis lived and the roles he played in the lives of noble Egyptian priests and pharaohs.

Worshiping a Bull as a Divine Emissary

The Apis bull served as a living embodiment of divine presence. Its deification was deeply tied to ancient Egyptians’ religious, political, and cultural beliefs. Being powerful symbols of strength, fertility, and kingship, bulls embodied qualities essential to both divine and earthly rule. Their physical strength and virility made them natural representations of life-giving power. The bull’s ability to sire numerous offspring reinforced its association with fertility, a crucial aspect of both agricultural prosperity and dynastic continuity. Therefore, bulls were not merely revered for their physical attributes but were considered sacred beings.

Divine embodiment was a core belief in Egyptian theology. Just as pharaohs were regarded as the manifestations of gods on Earth, the Apis bull was seen in life as the physical extension of the deity Ptah, god of life and creation. After death, the bull’s spirit merged with the god of the underworld, Osiris. These bulls were not chosen at random but had to meet strict physical criteria, believed to indicate their divine identity.

The Procession of the Bull Apis, painting by Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1879 (Source: Satinandsilk, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Procession of the Bull Apis, painting by Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1879 (Source: Satinandsilk, via Wikimedia Commons)

The presence of a living god among the Egyptian people created a tangible connection between the human and divine realms, reinforcing the ruler’s authority as an intermediary between mortals and gods. At the heart of this concept was the principle of ka – the spiritual essence that connected all beings to the divine. In Egyptian belief, deities, pharaohs, and even certain animals possessed a ka, which could be transferred or inherited.

An Apis bull had to exhibit specific divine markings, including a black coat, a white triangular marking on its forehead, a scarab-shaped mark under the tongue, and several other characteristics that proved it carried the ka of Ptah.

Importantly, the Apis bull was more than a mere representation of the god – it was divinity embodied in flesh. This understanding of sacred bulls as incarnations in life rather than symbolic stand-ins highlights the unique Egyptian perspective on the divine: The gods could walk among the people, not as distant, ethereal forces but as tangible, breathing beings. A living specimen of a bull was, therefore, the closest thing to a god – the god Ptah – that humans could interact with on a regular basis.

The Life, Death – and Afterlife – of an Apis Bull

Once a bull was identified as the new Apis, it was brought to the Temple of Ptah, where it lived in luxury befitting the embodiment of a god. It resided in a grand enclosure where priests attended to its every need, ensuring it was well-fed, groomed, and kept in pristine condition. It was believed that by caring for the bull, those select individuals were directly serving Ptah himself. Only high-ranking priests and certain officials were permitted to interact closely with the bull, reinforcing its divine status. The temple also housed a harem of cows reserved for Apis, as its virility was tightly connected to fertility – and the need to produce future replacements.

.png) Illustration of wall carving depicting various gods and Apis, the bull-god (Source: Auguste Mariette, via Wikimedia Commons)

Illustration of wall carving depicting various gods and Apis, the bull-god (Source: Auguste Mariette, via Wikimedia Commons)

Every day, the Apis bull was honored with ritual offerings, including bread, water, and incense, presented in elaborate ceremonies that acknowledged its divinity. Public processions were common, where the bull was led through the streets on special feast days. Large gatherings also took place at the temple, where worshippers sought blessings, fertility, and good fortune from the Apis bull’s presence.

The death of an Apis bull was a momentous event, marked by elaborate mourning rituals and a mummification process second to none. The bull’s body was embalmed using precious oils, linen wrappings, and sacred incantations. It was then placed in a specially built sarcophagus and buried in the Serapeum of Saqqara, an underground necropolis specifically constructed for Apis bulls.

In death, the bull was believed to merge with Osiris, the god of the underworld, becoming Osiris-Apis. Worshippers continued to venerate the bull after its death, leaving offerings at its tomb in hopes of receiving blessings from the afterlife. These tombs multiplied over the centuries, so that when Mariette, the archaeologist, explored the excavated necropolis, he counted in excess of 40 sarcophagi.

Auguste Mariette (seated at far left) with a distinguished viewing party including Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil (seated at far right), 1871 (Source: Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, via Wikimedia Commons)

Auguste Mariette (seated at far left) with a distinguished viewing party including Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil (seated at far right), 1871 (Source: Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Cultural and Political Significance of the Apis Bull

The Apis bull was not just a religious figure but also a powerful political symbol, reinforcing the divine authority of the pharaoh. Since the bull was considered a living manifestation of Ptah, and later Osiris, its presence in Memphis, where the Temple of Ptah was located, served as a visible confirmation of the gods’ favor. Pharaohs often sought to align themselves with the Apis bull, reinforcing their divine right to rule, in inscriptions and temple reliefs. The Heb-Sed festival, a rejuvenation ceremony for the pharaoh, often featured the Apis bull, further solidifying the connection between the ruler and sacred power – not to mention virility.

In Egyptian art and inscriptions, the Apis bull was depicted with symbolic elements that highlighted its divine and political importance. As noted above, it was depicted with a cobra encircling a Sun-disc, connecting it with Ra and the pharaoh’s divine sovereignty. Temple walls and objects of significance, such as carved scarabs, frequently featured images of the bull, often accompanied by texts linking it to the gods and the reigning ruler. The Serapeum, where massive stone sarcophagi housed the remains of the sacred bulls, showcased the lengths to which rulers went to honor and legitimize their rule through this divine being.

Beyond politics, the Apis cult played a crucial role in unifying Egyptian religious identity. The divine bull was venerated throughout the country, with pilgrims traveling from all regions to offer tribute at its temple. This widespread devotion helped bridge regional differences and reinforce a shared religious structure. Even during periods of foreign rule – such as the Persian and Greek occupations – the Apis bull maintained its significance, with rulers incorporating it into their own religious narratives to gain favor with the Egyptian people. The enduring veneration of Apis reflected both spiritual and political stability throughout the kingdom.

How Did the Apis Bull Cult Last So Long?

The worship of the Apis bull endured longer than any ancient Egyptian historical period, a testament to its deep religious and cultural significance. More than a mere representation of the gods, the Apis bull was believed to embody their spiritual essence, making its veneration a central part of Egyptian religious practice from the earliest dynasties to the Greco-Roman era.

_(follower_of)_-_The_Worship_of_the_Egyptian_Bull_God,_Apis_-_NG4905_-_National_Gallery.jpg)

Early Renaissance depiction of an Egyptian festival honoring Apis and Ptah (Artist: Follower of Filippino Lippi, collection of National Gallery, London, via Wikimedia Commons)

During the Late Period (664 BCE–332 BCE) and under Greek and Roman rule (332 BCE–641 CE), the cult of Apis evolved into the Serapis cult, a fusion of Egyptian and Hellenistic religious traditions that spread across the Mediterranean. In cities like Alexandria, Serapis was worshiped as a deity who blended the attributes of Apis, Osiris, and Greek gods like Zeus and Hades. The reverence for sacred animals continued in different forms, influencing religious traditions in the wider ancient world, including elements of Roman state religion and beyond.

Unlike purely celestial belief systems, Egyptian religion embraced the idea that divine power could manifest in the physical world, whether in the form of sacred animals or pharaohs. This belief in living embodiments of the gods created a religious experience that connected people directly to their deities. The Apis cult’s endurance across different eras and rulers reflects its powerful role in Egyptian identity, demonstrating how important the sacredness of animals was to their worldview.

The Decline – and Endurance – of Animal Worship in Later Eras

With the rise of Christianity and the eventual Christianization of Egypt in the 4th and 5th centuries CE, sacred animal worship was gradually suppressed. Early Christian writers, including Clement of Alexandria, criticized Egyptian animal cults as pagan, idolatrous, and outdated. As Christian influence spread, temples were abandoned or converted, and animal mummification, once a widespread practice, declined sharply by the late Roman period.

Despite this decline, the legacy of sacred animal worship endured in various ways. Elements of Egyptian religious symbolism were absorbed into later mystical and esoteric traditions, including aspects of Hermeticism and Gnosticism. The idea of divine embodiment in physical forms, which was central to the worship of Apis incarnate, can be seen echoed in later religious traditions – including Christianity – that emphasize holy relics, sacred icons, and the incarnation of divine figures.

The Apis bull remains a powerful symbol of the way the ancient Egyptians, and even later spiritual systems, viewed divinity: not as distant figures, but as present and tangible forces within their world.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. A journalist and communications specialist for many years, he writes on various topics, including Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (City Lights) and resides in Glendale, California.

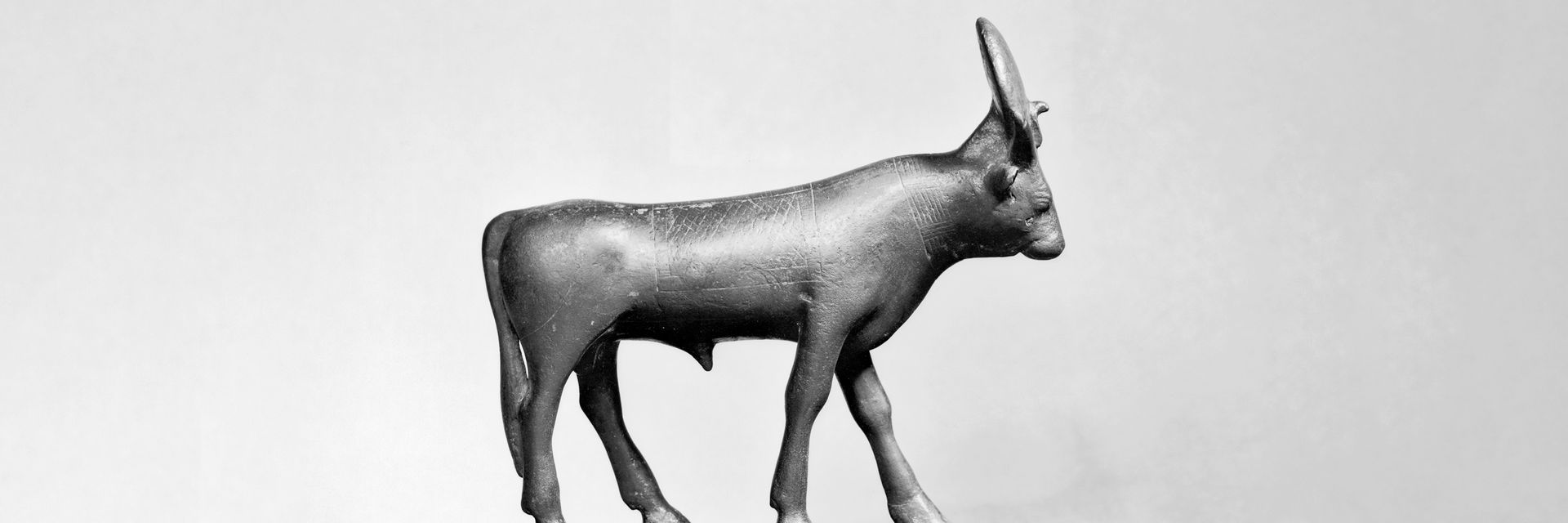

Title Image: Bronze statuette of the Apis bull, created between c. 550 and c. 450 BCE (Late Period) (Source: Walters Art Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)