In 1982, seven people in the Chicago area died after consuming cyanide-laced Tylenol. The killer remains unknown.

◊

Aches and pains are a reality for everyone, and Tylenol, a brand of acetaminophen, is a mainstay in any medicine cabinet. Anyone taking a Tylenol today is more than accustomed to peeling off the tamper-resistant, protective seal before accessing the bottle’s contents. But in 1982, such seals didn’t exist, and a series of deaths in the Chicago metro area were traced to Tylenol capsules contaminated with cyanide. The “Tylenol Murders” became the most media-covered story since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Despite the attention to the case, no one has been convicted of the crimes.

Why are some crimes never solved? Watch MagellanTV’s Donal MacIntyre: Unsolved to get some answers.

The Deaths

On September 28, 1982, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman stayed home sick from school. Her father, Dennis Kellerman, did what any father would: He gave her an Extra-Strength Tylenol. But soon, he knew something was wrong. “I heard her go into the bathroom…Then I heard something drop,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “I went to the bathroom door. I called, ‘Mary, are you okay?’ There was no answer. … So I opened the bathroom door, and my little girl was on the floor unconscious. She was still in her pajamas.” Sadly, Mary died before paramedics could get her to the hospital.

On September 29, Adam Janus, a healthy, 27-year-old postal carrier, took a couple of Tylenol. He became extremely ill within moments and was rushed to the hospital by family members. Dr. Thomas Kim, chief of critical care at Northwest Community Hospital, attempted to save Janus, but his efforts were unsuccessful. The doctor could never have expected what happened next. Shortly after Adam’s parents, brother Stanley, his wife Theresa, and Theresa’s brother Wally returned to Adam’s residence, the Arlington Heights Fire Department responded to a call from the household. Stanley and Theresa, they were told, had collapsed. They were both taken to Northwest Community, where Kim’s team would pronounce them dead.

Later that day, public health nurse Helen Jensen received a call from a firefighter who had responded to the Janus home. He informed her of the circumstances, and Jensen, along with Nick Pishos, an investigator with Cook County’s Medical Examiner’s Office, visited the Janus home. Expecting to find signs of carbon monoxide poisoning or, perhaps, botulism, Jensen was surprised to find nothing amiss in the household – though she did spy an open Tylenol bottle. “I counted up the pills and saw six capsules missing and there were three people dead. I said right then and there: It’s the Tylenol,” she told The Patch in a 2017 interview.

Jensen returned with the bottle to the hospital, where she told colleagues her theory. Initially, they dismissed the suggestion: How could multiple individuals experience such a sudden, extreme reaction to a common pain medication?

Unbeknownst to Jensen, doctors at Central DuPage Hospital were working to save new mother Mary Lynn Reiner, 27 years old, who had suddenly collapsed in her home. And in Lombard, Illinois, 35-year-old Mary Sue McFarland had also suddenly fallen ill at her place of employment, dying hours later.

Nick Pishos, having learned earlier of the death of Mary Kellerman and the Tylenol bottle found at the scene, requested officers bring it to him. He then contacted the deputy chief medical examiner in Cook County, Dr. Edmund Donoghue, who made a request: He asked Pishos to smell the two Tylenol bottles and tell him what he detected. Pishos confirmed Donoghue’s suspicions: The bottles smelled like bitter almonds, a scent unique to the chemical asphyxiant cyanide. Toxicologists soon confirmed that several remaining pills in the two bottles indeed contained lethal levels of the poison.

According to the New York State Department of Health, between 20 and 40 percent of the population does not carry the gene needed to detect the odor of cyanide.

A press conference was held to warn the public, and Johnson & Johnson issued a recall of the product. The company also offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to an arrest.

Paula Prince purchases Tylenol in the hours before her death and a bearded suspect is caught on camera. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The warnings came too late for 35-year-old flight attendant Paula Prince. On September 29, after failing to show up for her next flight, she was found deceased in her home. She was lying near her vanity, where there was also a bottle of Tylenol, a single pill removed. Newspapers published a haunting still image from a surveillance camera in the Walgreens where Prince purchased the Tylenol. It shows Paula in the last hours of her life. A bearded man also appears in the image, thought to potentially be the individual responsible for contaminating the Tylenol capsules.

The Investigation

A 15-agency task force was formed, which included 26 FBI agents. The case at their hands was unprecedented. The majority of homicides can be traced to individuals closest to the victims. Even serial killings involve a degree of victim selection, whether it’s occupants of a parked car on a dimly lit street or a woman home alone and watched from the shadows. The Tylenol Murders were uniquely chilling for their sheer randomness; there could be no telling who might pick up a tainted Tylenol bottle next.

Authorities zoomed in on the contaminated pills. The initial theory was that cyanide had been introduced into the capsules during production. However, the Tylenol bottles collected from the victims’ homes weren’t even manufactured at the same facilities, nor did the lots cross paths in transport or storage. That left the possibility that the tampering happened at the stores themselves, a theory backed by the fact that the remaining pills in the bottles had not become degraded from the cyanide crystals, suggesting that the capsules had been filled very recently.

(Credit: Vachagan Malkhasyan, via Pixabay)

In the coming weeks, multiple suspects emerged, most cleared for insufficient evidence. However, a dock worker named Roger Arnold became a person of particular interest. Not only had he worked with Mary Reiner’s father at a warehouse, but he was reported to the police by a bar owner who claimed he discussed killing people with a white powder. Arnold was never arrested, but the events did lead to another tangential tragedy. Arnold shot and killed a man named John Stanisha, mistaking him for the bar owner who had reported him to police. (He would be sentenced to 30 years in prison for the crime.)

On October 6, there was a break in the case. A letter arrived at the headquarters of Johnson & Johnson demanding that one million dollars be sent to a specified bank account or, it threatened, the killings would continue. A second letter arrived at the White House, alluding to the killings and threatening the life of President Ronald Reagan.

Investigators traced the letters to New Yorker James Lewis; police verified that his fingerprints matched those on the letters. Lewis also had a criminal past. In 1978, he had been charged with the murder and dismemberment of an elderly man (the charges were later dropped on a technicality). Lewis had also been convicted on six counts of mail fraud in 1981. He admitted to sending the letter, yet denied tampering with the Tylenol bottles; Lewis was ultimately sentenced to 10 years in prison on extortion charges, but investigators claimed that there wasn’t enough evidence to convict him for the actual poisonings. They couldn’t even prove that he was in Chicago during the murders.

Watch MagellanTV’s How to Catch a Killer to see how the police investigate murder in New Zealand.

Although never linked to more poisonings, in 2004 Lewis was charged with rape and kidnapping after attacking a woman in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The charges were dismissed after the victim declined to testify.

More potential suspects have been floated over the decades. These include Laurie Dann, a woman who, in 1988, opened fire in a Chicago-area elementary school classroom, and “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski, whose first homemade bomb detonated at a Chicago university in 1978. Though the anonymous nature of Kaczynski’s attacks might at first bear similarities to the Tylenol Murders, authorities ultimately cleared him.

Other theories have pointed back to the possibility that the poisoner was not a lone wolf crouched in the aisles of Chicago-area drugstores, but someone connected to Johnson & Johnson after all, perhaps working along the company’s Tylenol distribution chain. Johnson & Johnson was largely lauded at the time for its response to the crisis, but the company did face a series of lawsuits filed by victims’ families. (In 1991, the last of this litigation was settled out of court.)

Shockwaves and Copycats

While Paula Prince was the last victim in the Tylenol Murders, the Food and Drug Administration reported 270 occurrences of product tampering in the month following the incidents, including reports of straight pins in Halloween Candy Corn and Baby Ruth bars, razor blades in hot dogs, and sodium hydroxide-tainted chocolate milk. The majority of the incidents were proven to be hoaxes. Nevertheless, exaggerated fears about poisoned candy and, by extension, “stranger danger,” were both stoked by media outlets throughout the ‘80s and into the next decade.

Halloween poisonings are rare, but, in 1974, a man named Ronald O’Bryan gave cyanide-laced candy to five children, including two of his own. (Credit: CarrieLu, via Openverse)

The Tylenol Murders starkly exposed the lack of safety regulations in many popular products, and the potential dangers that could result. Changes came fast and furious. Johnson & Johnson created a more tamper-proof version of their pills, replaced capsules with gelatin-coated caplets, and – perhaps most significantly – began bottling their pills with tamper-evident packaging. Congress also enacted the “Tylenol Bill” in 1982, which makes it a federal offense to tamper with consumer products. Despite these silver linings of the 1982 tragedies, for the outraged public, and grieving families, there was still no justice for the seven decedents.

Justice Delayed: Chasing the Prime Suspects

Decades passed with little movement in the case. But it never went cold, not entirely. Advancements in forensics meant some answers were on the way.

In 2008, having served 15 years of his murder sentence, Roger Arnold died of natural causes. Having never fully dismissed Arnold as a suspect in the case, officials exhumed his body in 2010 and tested it for DNA; it wasn’t a match to the samples from the Tylenol bottles. That left one living prime suspect: James Lewis.

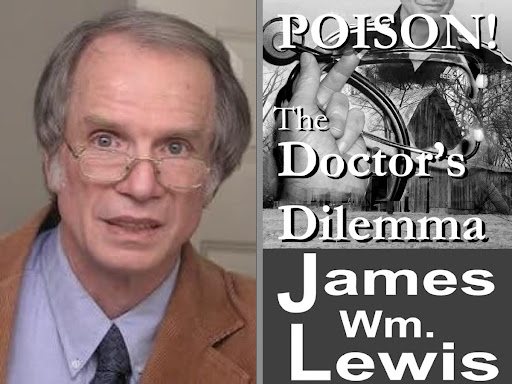

In the mid-2000s, investigators launched a covert operation worthy of its own movie. An agent went undercover as a journalist named Sherry Nichols. She claimed to be working on a book about the murders; Lewis agreed to speak with her about the case. (In a meta twist, Lewis wrote and self-published a novel about a series of poisoning murders in Chicago, called Poison! The Doctor’s Dilemma.) The agent spent significant time with Lewis in the hopes that he would slip up and provide incriminating information. Eventually, he did, which enabled the FBI to obtain a search warrant for Lewis’s residence, executed in 2009. Authorities also collected DNA samples from Lewis to compare against the bottles. Frustratingly, there was no match.

Lewis’s author photo (l.) and the cover of his book (Source: Amazon)

On August 4, 2023, Lewis was discovered deceased in his home. It would seem too late to either prove or finally exonerate the best suspect.

Following his death, video recordings of Lewis’s conversations with law enforcement were released to the public. In the recordings, Lewis offers an O.J. Simpson-level “If I Did It” narrative concerning the murders, detailing how a culprit might have gone about tainting the Tylenol capsules. Another video recorded during the sting operation (under the guise of traveling with Lewis for “research”), Lewis enters the Walgreens where Prince purchased her tainted bottle of Tylenol. He is recorded not only going to the back wall where Tylenol would have been stocked in 1982 but also commenting on how being there was like “deja vu.”

A new theory concerning Lewis’s potential motive for the crime has also come to light. Years before the murders, Lewis was a father to a daughter named Toni, who was born with a congenital heart defect. In 1974, at age five, Toni died after the sutures used in her heart operation tore. These sutures were manufactured by no other than . . . Johnson & Johnson. Could it be that the poisonings were motivated by Lewis’s misplaced grief and disdain for the pharmaceutical giant? For now, the answer remains unknown, the case in legal limbo.

A Painful Living Legacy

Despite the recent developments in the case, like so many events from the past, the Tylenol Murders have been largely eclipsed by more recent history.

For some, however, the tragedies remain front of mind.

In 2022, then-12-year-old Isabel Janus was tasked with writing a school paper about her family’s heritage. Instead of focusing on her Polish roots, she told a different story. Her paper explained how, when her mother Monica was just eight, she witnessed three members of her family die in a single day after consuming pills from a seemingly innocuous Tylenol bottle. The loss of these family members – Adam, Stanley, and Stanley’s wife Theresa – left an indelible mark on her mother’s and, by extension, Isabel’s life.

Today, popping a Tylenol comes with no second thought . . . and the protective seals on each bottle likely produce more annoyance than knowing gratitude. But, for the living members of the Tylenol Murder victims, there’s no such easy remedy for lasting generational pain.

Ω

Matia Madrona Query is a freelance writer and the editor of BookLife, the indie author wing of Publishers Weekly.

Title Image source: Pixabay