Why didn’t the U.S. and Russia blow up the planet? Give American strategic bombers some credit.

◊

Jets – the very word connotes a sleek, exotic force. From a Broadway musical (the “Jet Song” from West Side Story) to an NFL team (the New York Jets), the term conjures an immediate visualization of raw power and motion.

Today, we take jet engines for granted; they power the largest passenger planes and some of the smallest. Jet engines drive most of the world’s military aircraft. In the history of mankind, human flight is a dust speck; jet-powered flight is half of one.

The idea of a gas turbine or jet propulsion engine is deceptively simple. Air is forced into a tube, compressed by the action of the engine and mixed with fuel. The resulting superheated gases are forced out the back of the tube with so much thrust a multi-ton airframe can be easily lifted into the air. Like manned flight itself, the idea has been around for centuries. Various scientists and inventors tinkered with ideas and visual designs, but that’s as far as it went.

Get an up-close look at some of history's most iconic aerospace treasures in this MagellanTV series.

World War II Development

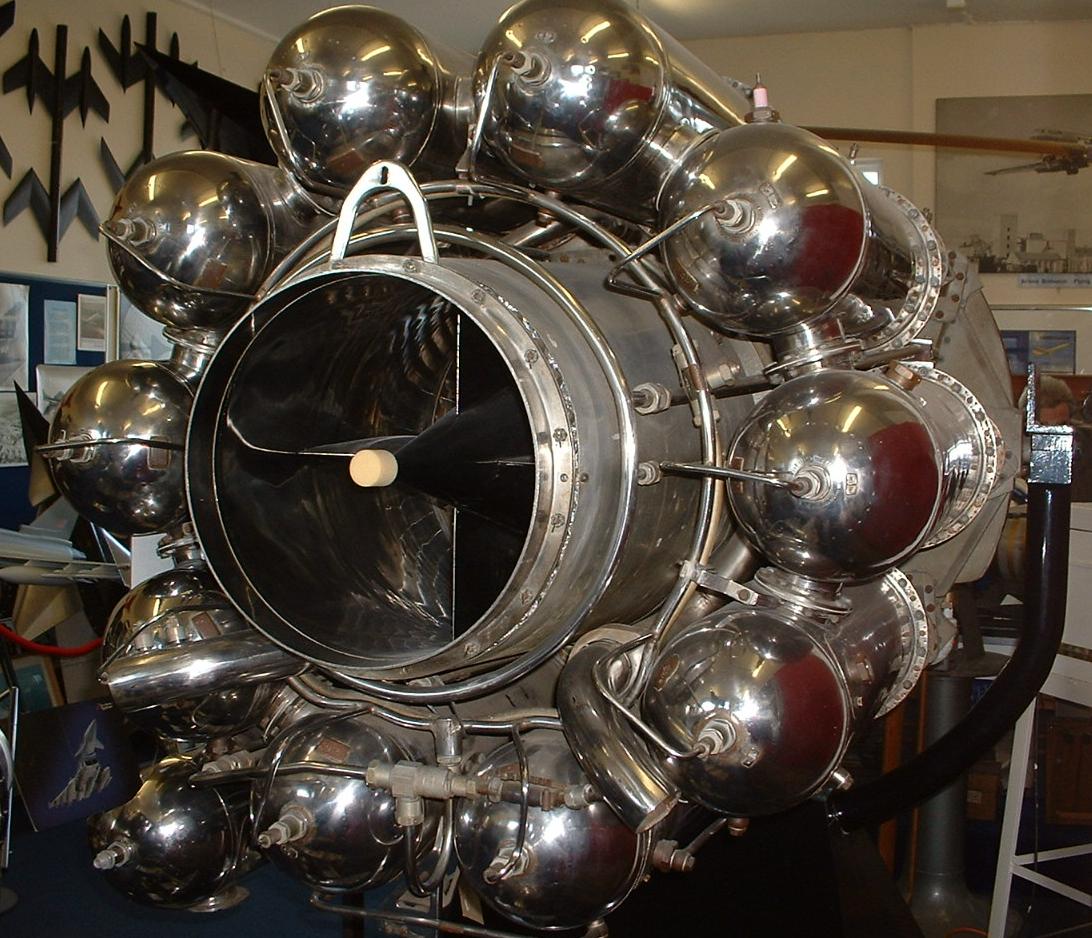

The jet propulsion research that led to the first practical engines was started simultaneously by British and German developers in the period leading up to World War II. Royal Air Force officer Frank Whittle patented his idea in 1930. With a team of British engineers, Whittle built a laboratory prototype that was successfully tested in 1937. By 1940, the British were aggressively pursuing the technology and, in early 1941, the United States learned of the project and had a Whittle engine shipped to the U.S. to be used as a manufacturing model by General Electric before year’s end.

Whittle laboratory jet engine (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Whittle laboratory jet engine (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1935 Nazi Germany, university student Hans von Ohain patented a turbojet design. A year later, one of the earliest airframe manufacturers, Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, pursued the idea and developed a jet airplane. Captain Erich Warsitz made the first turbojet flight in the He 178 jet airplane on August 24, 1939, at the Heinkel factory in Rostock, achieving a top speed of 435 mph. Other experimental units were built and tested in Germany, leading to the development of the first Luftwaffe production jets.

Forced to concentrate on bomber production, the only Heinkel jet produced was the late war He 162A fighter, with a single dorsal fin engine on top of the fuselage. The Luftwaffe leaned instead to producing the twin-engine Messerschmitt Me-262, the only German jet to see significant combat action in the war.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, the Gloster E.28/39 was the first Allied jet, built to test the new Whittle engine. By 1944, the production model, the Gloster Meteor twin-engine jet fighter, was being used to intercept Nazi V-1 flying bombs aimed at the U.K. The first operational U.S. jet, the Lockheed-built Shooting Star, entered service in 1945, too late to see World War II action. The single-engine jet fighter did see extensive action against Communist MIGs during the Korean War.

Gloster Meteor in flight (Credit: Chris Phutully, via Wikimedia Commons)

Ideology and Warfare

To what degree Allied strategic bombing affected the outcome of World War II will be debated forever, but one thing is certain – the American and British air forces achieved great success in impeding their enemies’ abilities to make war. Germany, primarily due to Adolf Hitler’s preoccupation with defeating the Soviet Union, never allowed the Luftwaffe’s long-range bomber program to grow. Japan, with its limited resources and multifront war, never had any successful strategic bombing initiatives.

The most significant events in the future of strategic aerial bombing came in August 1945, when the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima on the 6th and Nagasaki on the 9th. All of the World War II combatants had development programs for nuclear fission, but with the bombings, the Nuclear Age was born. The postwar United Nations was founded to bring former allies and enemies together in peace. But that is not the way the world turned. Soviet dictator Josef Stalin broke the Potsdam Agreement before the ink was dry. The Soviet Union quickly began to impose Communist puppet governments on countries it occupied, and erected what Winston Churchill famously called an “Iron Curtain” in Europe.

The defeat of the U.S.-backed Nationalist government in China by Mao Zedong’s Red Chinese, coupled with Soviet expansion, put a large segment of the world’s population under totalitarian Communist rule.

When the U.S.S.R. exploded its first nuclear weapon in 1949, the political rhetoric of Communist expansion took on a very real threat to world peace and security. The Cold War, a term coined by popular American columnist Walter Lippmann, was shaping future strategic military policy. The possibility of a global nuclear conflict was a bone-chilling reality. Well aware of this new threat was U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) general Curtis E. LeMay. An architect of strategic bombing in the Pacific Theater, LeMay saw the need for a new strategic air force that could act as a nuclear deterrent against the Soviet Union.

The Strategic Air Command

The reorganization of the USAAF postwar combat commands created the Tactical Air Command (TAC), Air Defense Command (ADC), and Strategic Air Command (SAC). LeMay and other leaders realized the WWII-era B-29 propeller-driven bombers would have neither the range nor speed to respond quickly if the Soviets launched a first-strike attack on the United States. A new fleet of jet-powered bombers was needed.

The United States Air Force was founded as an independent service in 1947 after a War Department plan to combine all air, ground, and sea services of the U.S. Army and Navy under a single head was defeated by the Navy.

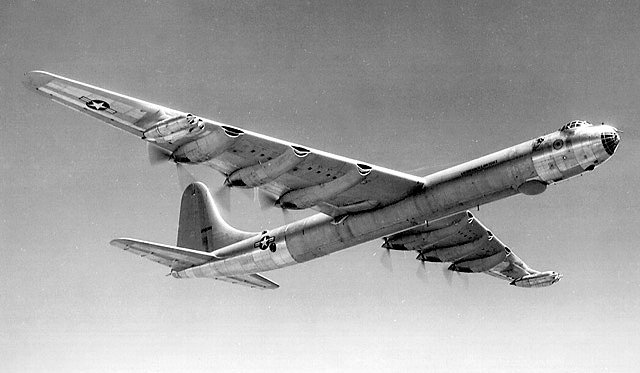

To address the need for speed, the first jet bomber was actually a hybrid. The Consolidated Vultee (Convair) B-36 Peacemaker, designed during the war and first flown in 1946, had six propeller engines at the rear of the wings and four jet booster engines that could take the aircraft from 230 mph to 435 mph. But it would take a pure jet aircraft to reach the 500+ mph the planners wanted to achieve.

B-36 Peacemaker jet-assisted bomber in flight (Source: U.S. Air Force, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bomb weight was another major consideration in the design of future jet bombers. Nuclear bombs are much heavier than conventional bombs. For example, the two bombs dropped on Japan weighed 8,000 (Little Boy) and 9,000 (Fat Man) pounds. Conventional bombs typically weighed 500 to 1,000 pounds.The B-36J model, which was first delivered to SAC in 1948, could carry 43 tons of nuclear or conventional bombs.

The Lockheed XB-43, the first all-jet bomber, was a medium tactical bomber. It never became operational. An ingenious solution called the “flying wing” was designed by Jack Northrop, founder of the Northrop Corporation. Based on the propeller-driven YB-35, the YB-49 long-range jet bomber had no fuselage and no traditional tail. Only three prototypes were made because the heavy bomber production contract was awarded to Convair to manufacture the B-36 instead. The flying wing design, however, would return to U.S. strategic bombers in the future.

North American Aviation, famous for the World War II P-51 fighter, entered the jet age with the long-range B-45, the first to be exclusively jet-powered. The straight-wing design reminded some of a late World War II Luftwaffe Arado bomber design that never entered production. The Air Force order of 200 B-45s was cut to 150 planes in postwar belt-tightening. The C model could be refueled in the air, making it suitable for long-range flights over the U.S.S.R. The plane also saw service in the Korean War, but engine problems forced the B-45 into retirement by 1957.

The Boeing B-47 Stratojet was the early star of the Air Force’s strategic bomber fleet. The swept-wing, six-engine plane began production in 1948. It took a few years for all developmental problems to be worked out, but the aircraft was pressed into SAC service in 1951. Here was a bomber that could reach high altitude speeds of greater than 500 mph and was capable of air-to-air refueling. This made the B-47 the answer to nuclear payload delivery over the Soviet Union.

World War II bomber pilot and Hollywood actor James Stewart starred in Strategic Air Command, a 1955 Paramount movie about a B-47 pilot. The Oscar-nominated film resonated well with Cold War audiences.

The B-52 Stratofortress – SAC’s Workhorse

Though the B-47 was thought to be SAC’s nuclear deterrent aircraft of the future, Boeing was already developing the jet that actually would be: the B-52 Stratofortress. When it debuted in 1952, it was a significant upgrade over all previous long-range bombers. Eight Pratt & Whitney engines produced a powerful 80,000 pounds of thrust.

By 1955, the B-52s were organized into large groups called wings, with an abundant number of aircraft and crews. They were based on several continents and supplied with nuclear weapons, which gave the U.S. a strategic bomber program capable of reaching all key targets in the Soviet Union. LeMay’s concept of keeping B-52s aloft for extended periods, utilizing air-to-air refueling, became SAC policy in periods of greater international tensions and higher threat-level alerts.

Air-to-air refueling of a B-52 (Credit: USAF, via Wikimedia Commons)

Air-to-air refueling of a B-52 (Credit: USAF, via Wikimedia Commons)

For their part, the Soviets were keeping pace in the nuclear arms race. They also had strategic bombers. The Tupolev Tu-95 Bear turboprop (propellers driven by a jet engine) was the first with the range to carry atomic warheads to the U.S. and then return to base. The more robust turbojet M-4 Bison followed.

By the late 1950s, both the U.S.S.R. and the U.S. were proceeding with programs to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles. The Soviets deployed their first working ICBMs in 1957, and the U.S. followed in 1959. But the need for a deterrent force of strategic nuclear bombers did not simply disappear. Among other advantages of manned bombers was the simple fact that, in a crisis, they could be deployed and then recalled, unlike ICBMs or their follow-on submarine-launched ballistic missiles. If the missiles were ever launched, there would be no turning back.

The launch of the Sputnik satellite by the Soviets in 1957 signaled the beginning of another Cold War competition: the Space Race, which consumed the attention of both superpowers through the 1960s.

The U.S.S.R.’s threatening capability had two major effects on U.S. war planning. One was a massive program to find where the Soviets were stashing their deadly nuclear arsenal. The USAF and the CIA, the American spy agency, used a variety of aircraft, including bombers, in surveillance missions to locate air bases and mobile nuclear launch platforms throughout the Soviet Union and its satellite countries.

The second effect was for America to set up its own ICBM program, also operated by the U.S. Air Force. Missile silos sprung up in unassuming locations that tracked a launch path over the Arctic ice cap – the same route that most SAC bombers took to reach the other side of the world. With the addition of Polaris ICBMs, which could be launched by the U.S. Navy’s nuclear submarines, the strategic triad of deterrence weapons systems was essentially complete.

The first dedicated spy plane, the Lockheed U-2, was used by the USAF and the CIA. (Credit: Staff Sgt. Brian Ferguson, USAF, via Wikimedia Commons)

The first dedicated spy plane, the Lockheed U-2, was used by the USAF and the CIA. (Credit: Staff Sgt. Brian Ferguson, USAF, via Wikimedia Commons)

While the B-52 program continued in full force, the USAF and its contractors continued to develop new bomber designs. The most ambitious program was to build the B-60, whose eight engines could propel it to over 2,000 mph. Tragically, one of two prototypes built crashed in a mid-air collision with an accompanying fighter jet. The program was canceled.

The next significant development in SAC’s weaponry was the Convair delta-wing B-58A Hustler. The long-range bomber could fly at supersonic speeds. The B-58 had no bomb bay; a single nuclear warhead or other payloads could be carried beneath the aircraft. Eighty-six jets of the Hustler model were delivered to the Air Force and used in the 1960s. They continued to break speed and distance records but, with their limited payload, were supplemental to the B-52 fleet.

Strategic Bomber Modernization – Successors to the B-52

After more than a decade without any new strategic bomber models, the USAF introduced the B-1B Lancer in 1986. It was the second attempt at a new program begun by Rockwell International and taken over by Boeing. The bomber has a top speed of 900 mph and can carry up to 84 general-purpose bombs. The four-engine Lancer first saw action in 1998’s Operation Desert Fox and has participated in other actions in which conventional bombs have been dropped. The Air Force began paring back the number of Lancers in 2002 to save money.

Northrop-Grumman prototype B-21 Raider in flight (Source: USAF, via Wikimedia Commons)

Northrop-Grumman prototype B-21 Raider in flight (Source: USAF, via Wikimedia Commons)

Building upon Jack Northrop's flying wing design of the 1950s, the B-2 Spirit program was begun just as the Soviet Union was dissolving, thus ending the Cold War. It did not see service until 1997, but it became the USAF’s primary nuclear payload bomber. It can operate at 50,000 feet and has a range of 10,000 miles with one mid-air refueling. Twenty-one B-2s were built, and they continue in service today.

As do the B-52 Stratofortresses. The venerable bombers continue to operate in training and other missions. The U.S. Air Force has a new program in development for the B-21 bomber that will replace both the B-1B and B-2 bombers. Perhaps it will finally also lead to the retirement of all operational B-52s. In any case, these long-range jets will continue to operate. As long as there is political instability in the world and military conflict is a threat, America’s watchword must be “strategic readiness.”

Ω

Jay Wertz is an award-winning author, publisher, and filmmaker. He has written seven books, including four volumes in the War Stories: World War II Firsthand™ series. Other books include The Native American Experience; The Civil War Experience 1861–1865; and Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, co-authored with Edwin C. Bearss. He is the editor and a primary contributor to D-Day 75th Anniversary – A Millennials Guide and other works for Monroe Publications. He has been a columnist and online contributor for Civil War Times Illustrated, America’s Civil War, Aviation History, Armchair General, and America in WWII magazines. He is also the producer-director-writer of the documentary series Smithsonian’s Great Battles of the Civil War for The Learning Channel and Time-Life Video.

Title Image: B-47H Stratojet (Source: National Museum of the U.S. Air Force)