Ada Lovelace was a 19th-century woman a century ahead of her time. Her friendship with inventor Charles Babbage allowed her to envision a world where computers would not only calculate, but create.

◊

As a child, Ada Lovelace dreamed of flying. But Ada was no ordinary child. Where other boys and girls might daydream of floating with the clouds, drawing pictures and inventing stories, little Ada approached her goal as a young scientist would. In 1828, at the age of 12, she displayed her creativity and inquisitive nature by conducting experiments on the feasibility of human flight. In a manner similar to the musings of Leonardo da Vinci, she analyzed the anatomy of birds and flying insects and explored the structure of wings. She went so far as to experiment with lightweight materials, constructing sets of child-sized wings out of paper and feathers. She even composed a book detailing her experiments, titled Flyology, in which she drew a diagram of a steam-powered flying horse.

This anecdote offers only the merest suggestion of the woman Ada would grow to become. A fearless and daring thinker, Lovelace had the imagination, which she termed “poetical science,” to conjure a world wherein amazing “thinking machines” would be set free to serve human needs. They would calculate complex equations and even create unique works of synthetic art, design, and music through the punch-card input of an enlightened computer programmer.

That she imagined such marvels a century before the dawning of the electronic age, the era of miniaturization, and the invention of silicon-based computer chips, is all the more wondrous. Coming from the 19th-century “Mechanical Age” of steam-powered engines, it represents a tale of almost “steampunk” derring-do.

Steampunk is a literary genre of the late 20th century indebted in no small manner to the imagination of Ada Lovelace. Briefly, it posits an imagined Victorian Era where all kinds of astounding inventions, from computers to robots, have been made possible through steam-engine technology. In fact, the novel credited with kicking off the genre is 1990’s The Difference Engine, co-authored by sci-fi writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, and a fictionalized Ada Lovelace plays a role in its plot. Her great achievement in life easily qualifies her to be a steampunk heroine: She foresaw the entire future of a computerized society from her perch at the height of the Mechanical Age.

There’s much more to Ada Lovelace’s fascinating life than envisioning computers. Be sure to check out Calculating Ada: The Countess of Computing.

The Early Education of Ada Lovelace, Child Prodigy

Just as Ada, the Right Honourable Countess of Lovelace, was no ordinary child, neither was her childhood an ordinary one. Born into family wealth and status, particularly on the side of her educated and politically enlightened mother, Baroness Anne “Annabella” Milbanke, Lovelace was blessed – though some considered it “cursed” – to have as her father the great Romantic poet and charismatic vagabond, Lord Byron.

The marriage of Byron to Annabella was brief and tumultuous. Once wedded, Annabella grew suspicious of her husband’s wild ways. She had reason to believe he had “sown his oats” rather indiscriminately prior to their marriage, but then she heard he might actually have incestuously bedded his half-sister Augusta. Annabella cut off contact with the poet quite abruptly and vowed he would never have any role to play in the upbringing of their only child.

Byron soon left the country and died in a rather spectacular, swashbuckling way in Greece some years later. And Annabella guided her daughter’s education to avoid any possibility that she might grow up in his “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” footsteps by forbidding Ada to be schooled in literature and poetry. It was only science and mathematics that the concerned mother prescribed for the young girl.

This suited young Ada well. Her mother could afford the finest private education, and Ada showed herself to be quite the precocious student. She took to advanced mathematics exceptionally well, certainly above the expectations of Augustus De Morgan, her tutor, who resisted the concept that women, with their “smaller minds,” could be educated to the level of their “natively superior” male counterparts.

Ada proved his prejudices ill-founded.

Ada Lovelace (left), portrait (possibly) by Alfred Chalon; Charles Babbage (right), 1860 photograph. (Sources: Science Museum Group (l.)/Public domain (r.), both via Wikimedia)

Inventor Charles Babbage’s ‘Difference’ and ‘Analytical’ Engines

In 1833, at age 17, Ada was introduced socially to Charles Babbage, 14 years her senior, a man well-known in mathematical circles for his audacious attempts to create a mechanical calculating machine. This (never fully built) invention, which Babbage termed the Difference Engine, aimed to make foolproof the development of mathematical tables. In the 19th century, such tables were ubiquitous in science and industry. They were used as the bedrock of everything from architecture to astronomy. An error in calculation – or even in copying – could be disastrous. And errors there were.

Babbage was known to complain, loudly, about the human errors that crept into mathematical tables. Once, while laboring over tables he knew had multiple mistakes, he exclaimed, “I wish to God these calculations had been executed by steam!”

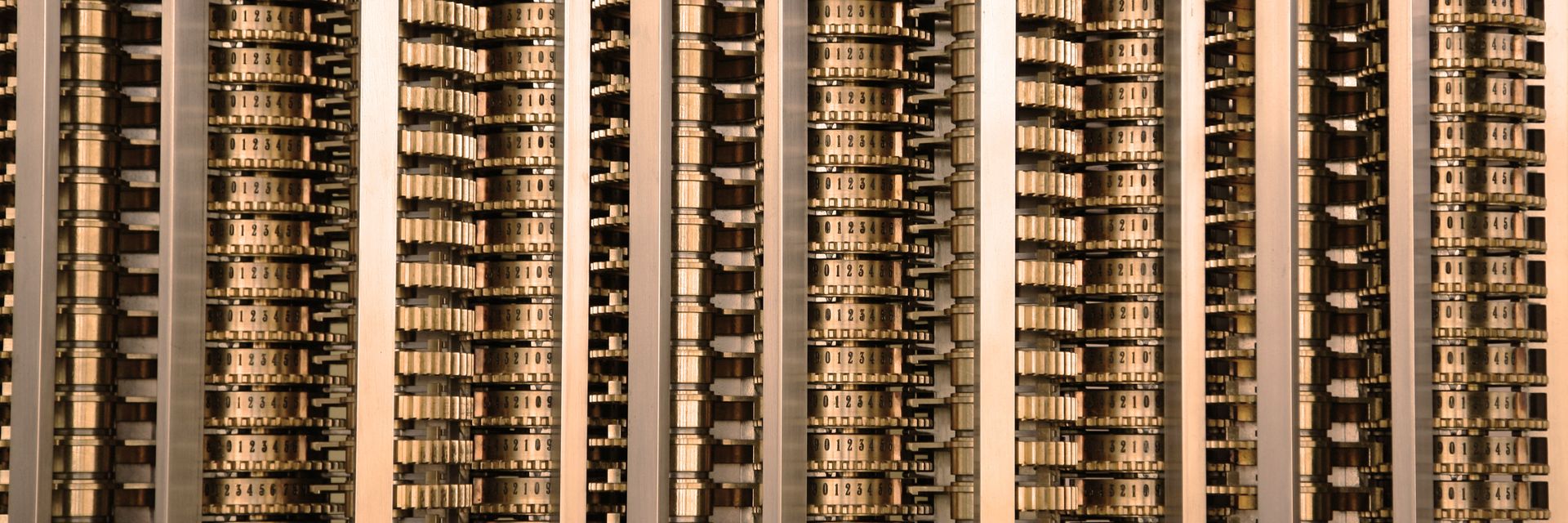

Babbage intended to overcome the vagaries of human error with his machine, which might, in today’s terminology, be called an “abacus on steroids.” Conceived to be steam-powered (his model was hand-cranked), the Difference Engine was designed to do complex mathematical calculations out to 30 digits. Babbage was convincing enough that the British government subsidized his project to the tune of £17,000 over ten years (approximately £2.2 million, or $2.75 million, today) before finally backing out.

You see, Babbage was a bit of a demanding blowhard. His continual entreaties to the government to support his research caused some to turn against him. After Babbage’s final, unsuccessful appeal for increased government funding, then-Prime Minister Robert Peel wrote in exasperation, “What shall we do to get rid of Mr. Babbage and his calculating machine?”

Despite his chronic lack of funding to achieve his dreams, Babbage kept on pushing, and conceived of an even more complex device called the Analytical Engine. This concept (also never built) went beyond the Difference Engine’s mathematical abilities and promised to compute any equation using punched cards and a system of gears and levers.

.jpg)

Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine (no. 2), on display at the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California (Source: Erik Pitti, via Wikimedia)

Babbage believed his Analytical Engine would be able to perform any calculation, not just numerical ones. One of the most notable features of the proposed Analytical Engine was its capability to execute conditional statements (i.e., if A, then B queries) and loops (e.g., rerunning the same query until a desired condition is met). These are essential components of modern computer programs, and Babbage was first to the game.

A Meeting of Minds and Imagination

When Babbage explained to Ada the workings of the Analytical Engine, she understood him implicitly. Her mastery of advanced math, mixed with her penchant for “poetical science,” may even have given her an advantage in seeing the promise of such a machine.

The two “great minds” of computer prehistory now even have their own literature, a steampunk graphic novel titled The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Computer, written by Sydney Padua and published in 2015.

Babbage and Lovelace maintained their friendship through years he spent tinkering and retooling and she spent establishing a family, with three children. Nearly 10 years later, in 1842, Babbage requested her assistance with a project to further the promotion of the Analytical Engine in England. Babbage had given a lecture in Italy on his project, and an attendee, Luigi Menabrea, wrote an essay based on the lecture in French. Since Ada was fluent in the language, Babbage suggested that she translate it for publication in England. She agreed not only to translate the essay but to add voluminous notes, prepared in collaboration with the inventor, that would further explain its promise.

Her writing, which she simply titled “Notes,” was fortuitous and visionary. If it had only been recognized in her lifetime, we might indeed have had a “steampunk” fin-de-siècle in London. As it was, the essay was published to little note, only to be discovered a century later by another computer forerunner, Alan Turing, who gave it the promotion it needed at a time when it could finally be appreciated.

In her “Notes,” Lovelace wrote:

Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.

Seeing how the Analytical Engine could be “programmed” to compute results beyond pure math, Lovelace in a sense foresaw our modern, computer-dominated world. She is justly celebrated now as a “mother” to computer programming and a patron saint of women in STEM. In fact, a programming language called ADA got its name in her honor.

Early Computing Comes to a Premature End

Despite their efforts, Babbage’s own headstrong nature may have put the final nail in the coffin for the Analytical Engine – at least during his lifetime. After Lovelace’s “Notes” was published, she wrote a lengthy letter to Babbage offering help with promoting (and funding) the Analytical Engine project. She felt, simply, that she could represent the project better to others than could the irascible inventor.

Disastrously, Babbage refused her assistance, effectively ending their working relationship and any chance of gaining a foothold in the public’s imagination during the 1840s. Ada, the Countess of Lovelace, returned to her comfortable private life and died prematurely of cancer in 1852, at age 36. Babbage continued working in obscurity until his death in 1871. Computer programming, and its world-changing consequences, would have to wait another century.

Feisty Ada Lovelace blazed a unique path through Victorian England. She raised eyebrows by wearing trousers when inspecting machinery such as Babbage’s, and her fascination with numbers led to a keen interest in “odds” – especially when it came to betting on horse races. In fact, she wagered so profligately with her close circle of male friends that her mother kept a tight rein on her purse strings. MagellanTV’s superb documentary Calculating Ada: The Countess of Computing presents Lovelace’s life story in all its complexity and joie de vivre.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on various topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Charles Babbage designed his “Difference Engine” to perform mathematical equations mechanically. (Source: Jitze Couperus, via Wikimedia Commons)