[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in January 2019.]

Impressionism was an art movement comprised of strong personalities, and most of them – Gaugin, Van Gogh, Monet, et al. – were men. But what about their female peers? Four women stand out: Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Marie Bracquemond, and Eva Gonzalès. If we think of them at all, we’re most likely to perceive them and their work as “domestic,” “delicate,” even . . . “feminine.” But there’s a lot more to these artists than these gendered words can capture. Let’s see what factors may have prevented them from receiving the same recognition as their male compatriots.

◊

Impressionism is now among the best-loved art movements of all time. But at the time it arose, a more common response would have been howls of derision. Breaking with their academic, studio-bound, history-painting predecessors, the Impressionists made color-drenched compositions of myriad subjects, primarily in their natural environment. They utilized the passage of light through scenes to mark singular moments in time. No one had ever seen anything quite like it.

So keen were the Impressionists to expand the breadth of color choice that there was a firm, though unwritten, rule against ever using the “noncolor” of black in their works.

Technical advances allowed artists to venture out into the sunshine, and work en plein air, outdoors, carrying their portable easels. Freed from the studio, they wandered gardens, fields, and even the urban environments of bars and cafés in and around Paris. Indeed, the modern city and its stylish habitués became central to the interests and concerns of the Impressionist avant-garde.

Image Source: Children Playing with a Cat, Mary Cassatt (1908), via Wikimedia Commons

However, this emergence into natural landscapes and city scenes was not immediately available to all painters in the movement. In fact, when we view the best-known images created by women Impressionist artists, we are invited into a much different world – a world of interiors, walled-in gardens, still lives, pets, animals, and children galore. So many children. Why such a difference in themes?

“Proper Ladies” of Paris, and the Denizens of the Demimonde

To understand the disparity, it’s instructive to examine societal norms of the day to gather some clues. First of all, though modernity had evidently progressed in the Industrial Age city of Paris with its active nightlife, “proper” women still had no business out in the city streets, except when accompanied by chaperones to maintain decorum.

In the 19th century, there was a bright line that separated “proper” Parisian woman from those of “lesser,” or, let’s say, “looser” morals. And visiting Parisian night-spots – especially unaccompanied – was definitely on the far side of that line.

It’s not that women were not to be found in the cafés and music-halls of Paris in the très gai 1890s, it’s just that they were most likely to be transactional women for whom, to be frank, time meant money. Participating in the demimonde (literally: half-world) of Parisian nightlife, with its gambling, drinking, and carousing, was generally acceptable for men, but for an unaccompanied woman, it was taboo. And the class of women that participated in these nighttime entertainments simply wasn’t spoken of in the polite society of marriage and family life among the upper classes.

Women Artists Suppressed behind Social Strictures

Each of the women we’re focusing on – Cassatt, Morisot, Gonzalès, Bracquemond – was a member of the haute bourgeoisie. Not only could they afford the art supplies necessary to become working artists, they also had the money – family or personal – to hire professional painters to teach and mentor them.

Even after women were allowed to attend art classes under certain circumstances, they were forbidden from life study classes. That is, they were disallowed from viewing nude models, as it was deemed inappropriate for a women to fix their gaze on a naked man, or even a naked woman. In place of life study, women were limited to drawing from casts, or even farm animals like horses or cattle.

Hiring teachers from the ranks of accomplished artists was necessary for the education of the women, who were systematically excluded from participating in art education programs in the capitals of Europe (and many institutions in the U.S., as well). Creating art was seen essentially as a male activity, and there was no role for a woman to play in this world at that time. In fact, it seems outrageous to modern sensibilities that women were refused entry at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris until 1897.

Given the norms of the time, however, women were forced to navigate an environment of pronounced difficulty and lacked even the agency to travel alone without chaperones. In their studies, women had to rely on men to learn and practice their art. And these men did not always have their students’ best interests at heart.

Marie Bracquemond: Career Cut Short by a Jealous Husband?

Marie Bracquemond, for example, studied with the painter Ingres, whose hatred of the styles of the modern era (Romanticism, then Impressionism) may have helped Bracquemond excel in technique. An early painting of hers was even accepted into the annual Paris Salon. But Ingres was far from an ideal mentor; his lack of faith in women’s potential as artists led him to insist that women be trained only to paint flowers and fruit – women’s work – rather than to portray men and women as subjects.

Image Source: On the Terrace at Sèvres, Mary Cassatt (1880), via Wikiart, Public Domain

Bracquemond chafed under the control of her imperious instructor. When she was introduced to the Impressionists Monet and Degas and absorbed their striking work, she was delighted to find not only a new style of painting, but also a wide palette of vibrant colors drawn from nature and a novel technique of working in open air.

Bracquemond’s art, which had nearly completely fallen out of public awareness until it was resurrected by feminist art historians in the 1980s, displays a loose and intriguingly fluid way of handling paint on canvas, with well-modeled figures and backgrounds dominated by brushwork that brought a lively feel of air moving through the scene.

But Marie’s path to accomplishing her goals of painting in the Impressionist style was hindered, to say the least, by another important man in her life – her husband. Félix Bracquemond, an artist himself, was taken with etching and printmaking and for a while was the artistic director of Haviland china, designing patterns in the decorative styles of the day.

Félix despised the avant-garde style of Impressionist painting and was appalled by the profligate use of bright colors Marie preferred. He harassed and diminished his wife for painting in that style until, to keep peace in the family, she put away her easel and oils. She continued to produce numerous etchings but gave up painting entirely. In fact, we are lucky to know of Marie’s painting at all, given her husband’s desire to diminish her professionally and separate her from her artistic peers.

In the end it was the Bracquemond’s son Pierre who saved his mother’s canvases from probable destruction. Given the heartbreak she must have felt, we should be thankful to Pierre for ensuring that his mother’s paintings have survived.

Eva Gonzalès: Was She Too Close to Manet?

Eva Gonzalès began her professional career studying with – as well as occasionally modelling for – Édouard Manet. A famous painting by Manet of Gonzalès shows her seated at an easel ostensibly working on a still life of, notably, flowers in a vase. However, instead of portraying her realistically, in a smock or other attire suitable for working with pigment and canvas, he showed her resplendent in a beautiful and clearly expensive gown of silk and lace. That apparel emphasized her upbringing and social status admirably, but at the expense of depriving her of the dignity of appearing in a more natural manner.

Image Source: Eva Gonzales, Edouard Manet (1869-70), via Wikiart, Public Domain

The Manet portrait, and the image it conveyed, hindered Gonzalès’s reputation. Rather than being depicted as an artist in her own right, critics believed it showed her as a poseur, a model rather than artist, and – based on how she was painted – possibly a mistress to the older man.

Despite her undeniable promise and the completion of a strong body of work, Gonzalès’s career was tragically cut short. She died giving birth to her only child, Jean, in 1883, at the relatively young age of 34.

Gonzalès’s work clearly shows the influence of her mentor Manet. Her work reveals an expert technical understanding of how to convey light – direct, reflected, and filtered – on her subjects. Children are depicted with ruddy, sun-dappled complexions; adult women appear with fashionably made-up faces that sometimes show the influence of japonisme, or Japanese artistic style.

Berthe Morisot: Gaining Entry to the Men’s Club

Berthe Morisot, whose works were also accepted both by the official Salon and Impressionists’ exhibitions, commenced her art instruction with the landscape painter Corot, who instilled in her his own enthusiasm for working out of doors. As her work progressed, she retreated into private spaces to paint, due to the strictures against women unaccompanied in public. She was even forbidden by the Louvre to sit in their galleries, sans chaperone, to sketch copies of the art there, as men were accustomed to do.

Image Source: Woman Hanging Out the Wash, Berthe Morisot (1881), via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Morisot depicted members of her family, usually on a small scale, in private gardens on their family property or in interiors. In contrast to the heroic scale of many male painters of the day, her paintings often showed children in their nurseries being tended to by nannies or female family members. Such scenes were deemed acceptable because their extreme intimacy was seen as the exclusive domain of women. Adult men would never be seen doing such “women’s work.”

Morisot was influenced by many of her peers, including especially Manet, her brother-in-law. She also acknowledged the influence of Renoir, whose use of light and shadow on figures was an inspiration to her. And the work of Edgar Degas influenced her to expand her color palette and the use of mixed media in her paintings, incorporating drawing, watercolor, pastel, and oil all in the same artwork.

Mary Cassatt: A Devotion to Mothers and Children (or a Trap?)

Mary Cassatt, the sole American in this group, began her art studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Not at all a shrinking violet as a student, she complained of learning “nothing,” since women were limited to working with inanimate objects – and, of course, life drawing was off-limits to all women.

Image Source: Reine Lefebre and Margot before a Window, Mary Cassatt (1902), via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Moving to Paris, Cassatt encountered similar obstacles, but with a French twist. Like her female peers, she was excluded from enrolling in the École. But being of independent means through family money, she could afford private lessons from members of the École, such as the academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. However, under the strictures of Parisian society, she was limited socially by being an independent woman, and consequently was not allowed to participate in evening entertainments in cafés and other boîtes.

Mary Cassatt is recognized for her groundbreaking particularity in depicting intimate relationships – husband and wife, mother and child. Notably, she had no children of her own, and she never married.

Cassatt’s initial paintings were acceptable to the taste-makers of the Salon, and several were accepted. As she began to absorb the influence of Impressionism, though, her works were rejected. But the setback was temporary, and she was invited by Degas to show her work with the Impressionists in their exhibition of 1886.

Cassatt is known for her many intimate paintings of mother and child. She is celebrated for the psychological incisiveness of her portraits, which reveal the many shades and emotions that mark a mother’s love. Though her work focused on female domesticity, her goal was to show a type of female who was not retiring, but rather was socially active and aware of her surroundings.

Being a “Woman Artist” in a Man’s World

Bracquemond was forcefully convinced by her husband to stop making Impressionist paintings. Gonzalés and Morisot were guided to make “feminine” paintings. Even Cassatt, independent though she was, devoted herself to making “female-friendly” art that was acceptable to the men in her midst. But Cassatt disliked being called a “woman artist,” and wanted her work to be seen as the equal of – or even superior to – work by her Impressionist peers.

Gonzalès, in fact, had her large-scale work Box at the Theatre des Italiens rejected by the academic Salon for its possessing too much “masculine vigor,” especially in its lively brush work. Its vibrant style led some Académie members to presume that it had been primarily painted, or possibly finished, by a man, so it went undisplayed.

So, how are we to respond to this “female” art? Should we look at it as intrinsically inferior to the work of men because of subject matter – or even due to the relative “vigor” of temperament and style? From our point of view in the 21st century, that would seem an absurd proposition.

Women were allowed to see paintings with naked figures in museums and other exhibition spaces, but they were not allowed to visit museums to sketch the paintings there unless accompanied by a chaperone. Even so, due to the customs of the time, “proper” women were expected not to stare at the paintings of figures. (Men were allowed to look, but not to leer.)

Beginning in the 1840s, in Paris and other cultural capitals on the Continent, the concept of the “New Woman” began to arise. There were calls for women’s suffrage, and ideas about independence of thought and social standing – ideas now associated with “first-wave feminism” – began to circulate. Though it took many decades for these ideas to spread widely, there were proponents who affected some of these women artists even during the heyday of Impressionism. As scholar Meaghan Clarke points out, there were numerous women art critics by the late 19th century who promoted and discussed both male and female Impressionist artists.

Finding a Place in the Pantheon for Women Artists

In our time, of course, there are many women art critics and writers who have reconsidered the value of women artists in the 19th century. Regarding Marie Bracquemond, for example, we might ask whether we should primarily consider her story tragic due to her husband’s short-sighted male chauvinism; or should we instead celebrate the great works that she was able to make during her lifetime and get into public view? Perhaps there’s room for both, while spending most of our attention on her lively and colorful work.

And, despite her work being rejected for being “too masculine,” Eva Gonzalés had her defenders. One, the art critic Maria Deraismes, championed Gonzalés’s work for challenging the way women painters were viewed in – and separated from – the Parisian art scene.

More recently, the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin, who died in 2017, was responsible for one of the most important texts on feminism and institutional sexism in the arts. In “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?” (1971) she treats these issues at length, as they have existed in the past and endure into contemporary times. Nochlin honors the path women had to take in the past to express themselves through art:

. . . for a woman to opt for a career at all, much less for a career in art, has required a certain amount of unconventionality. . . . [She must] have a good strong streak of rebellion in her.

In the same essay, she writes that women must, in fact, align themselves with certain traits once believed to be “masculine”:

- Singlemindedness

- Concentration

- Tenaciousness

- Absorption in ideas and craftsmanship for their own sake

So, let us not forget that these women artists succeeded in crafting paintings that delight the eye – in their time and in ours – just as their male counterparts did. They were Impressionists through and through, and despite many individual and structural setbacks, they made art that endures. They may not have felt it in their day, but, with several layers of anti-female bias challenged and discarded over the past 150 years, we can see their accomplishments, celebrate their art, and honor their spirits, which led them to generate extraordinary and exquisite images for their social circles, their eras, and their artistic legacies.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

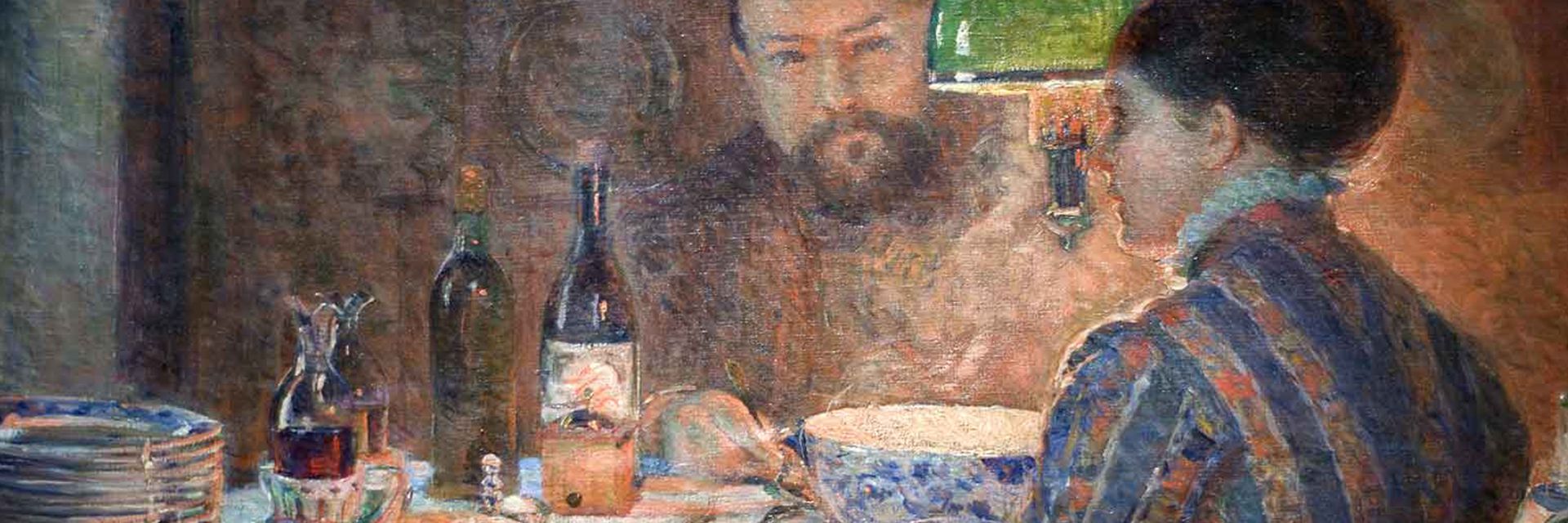

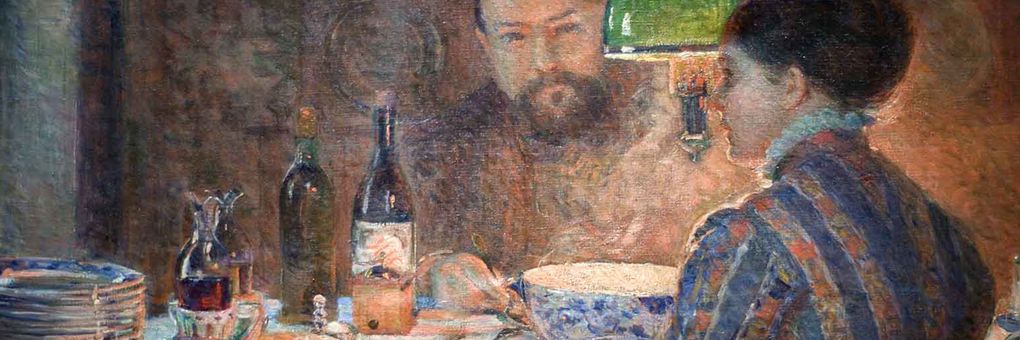

Title Image: Marie Bracquemond: Under the Lamp, 1887. (Via Wikimedia Commons)