Historians agree on Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.’s gift for masterful oratory, but some addresses stand out as especially impactful.

◊

Perhaps most famous for his I Have a Dream speech at the historic March on Washington in 1963, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. gave more than 2,000 sermons and addresses to audiences across the country in a single decade before his death. Each of these powerful orations illustrated his Christian fervor, uncompromising morality, and magnanimous personality.

In three of his most powerful messages, King discussed a variety of important topics about which he was both knowledgeable and passionate. In celebration of Martin Luther King Day, let’s focus on three outstanding statements he delivered as he solidified his position on the right side of history.

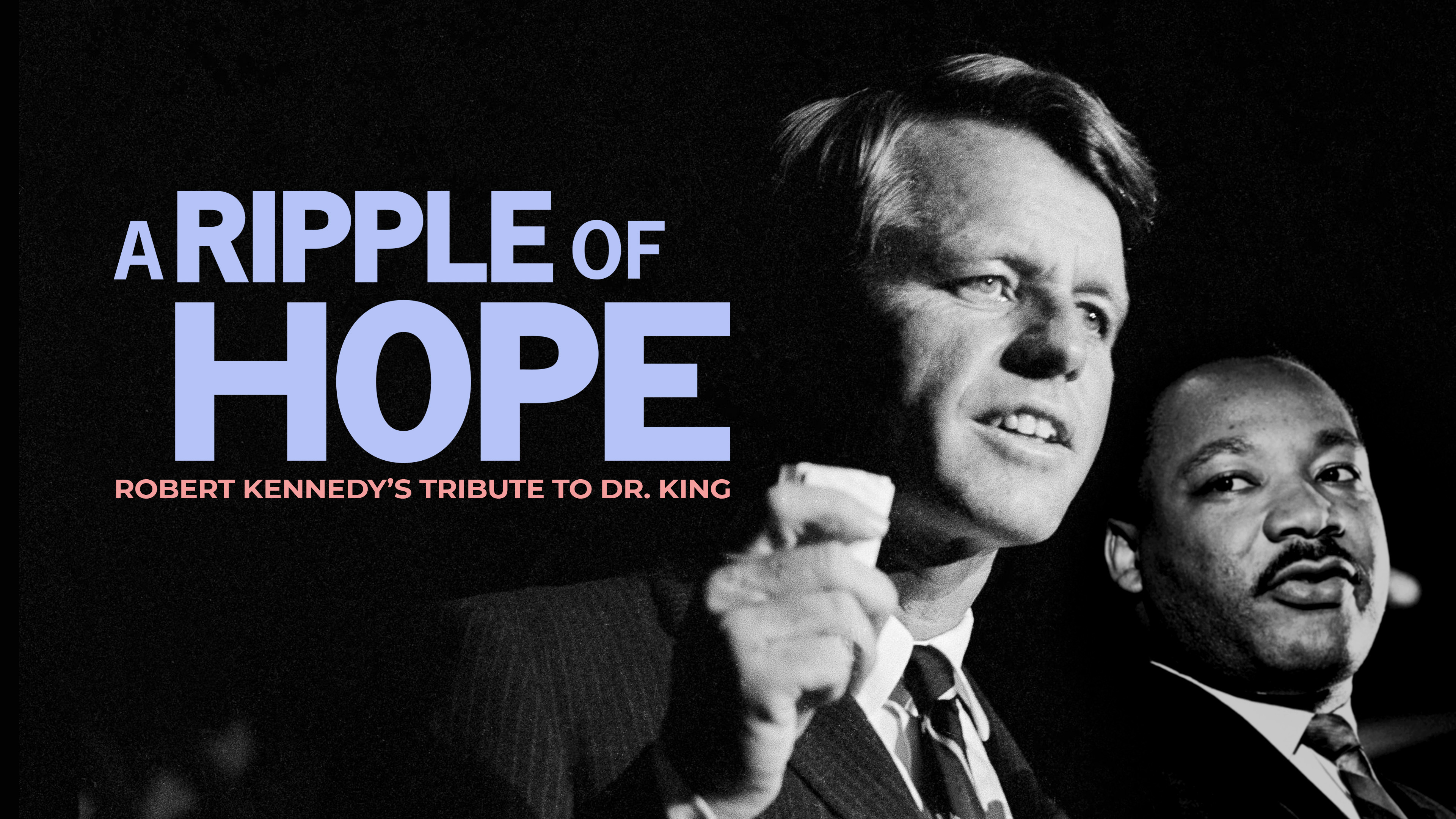

Robert F. Kennedy's speech on the night of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination was a true profile in courage.

‘Give Us The Ballot’

The Reverend King opened this speech with praise for the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown vs. the Board of Education that the racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. He viewed this result as a step in the right direction and a substantial victory for all citizens in the United States.

Unfortunately, racist opposition to the court’s ruling included the obstruction of voting rights for Black Americans across the South. King emphasized the importance of voting in this address, framing this sacred activity as the primary means by which Black Americans could protect themselves from violence and substantially improve their lives.

Next, King asserted that, beyond protecting the voting rights of Black Americans, different groups of White people needed to show up for racial justice. Northern liberals couldn’t let centrist philosophy keep them from committing to morality, King asserted, while southern conservatives were obligated to declare their support for Black people in the face of potential ostracization from racist peers.

‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail’

Not a speech per se, King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is among the greatest messages to the American people on the subject of civil rights. Like a close friend, King wrote comprehensively and constructively about his disappointment with White moderates, conceding that Black people were more frustrated by lukewarm tolerance than by outright hatred.

At the beginning of the letter, King noted how his fellow clergymen had found his “direct action” too extreme. His response was to remind them of everything else he’d tried before resorting to direct action, which had landed him in the jail from which he wrote.

White moderates were constantly telling Black citizens to “wait” for justice, as if there would be an opportune time to fight in the future. In particular, they encouraged King to use “negotiation” instead of direct action, but King had already tried to negotiate with those who would obstruct justice. He further asserted that nonviolent direct action would lead to the most fruitful negotiation by forcing all members of a community to engage to resolve existing tension. Thus, direct action was a necessary step in opposing injustice.

Despite King’s profound disappointment, he viewed his White colleagues as brothers in Christianity and promised that his disappointment came from a place of love. Had he no love for the church, he wouldn’t have specifically expressed disappointment with White clergymen’s inefficacy in the struggle for racial justice. He had simply expected more, and he expressed his disappointment with the utmost respect.

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the White House, March 1966. (Credit: Yoichi Okamoto, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the White House, March 1966. (Credit: Yoichi Okamoto, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

Beyond Vietnam

When King began his discussion of the war in Vietnam at a 1967 conference, he stated that many of the people he had met had failed to understand why he spoke out against the war with so many civil rights issues already on his plate. His first response was to clarify how directly civil rights and the Vietnam War were connected.

He emphasized that the effort to eradicate poverty was on behalf of all poor people without regard to race. Though politicians had begun to consider possible reforms to benefit the poorest people in the U.S., the Vietnam War hijacked the nation’s budget and attention, disrupting the domestic fight for civil rights.

Next, he lamented the irony of the Vietnam War: Black men, many of whom were barely older than boys, fought and died in the interest of another country’s welfare without living in a free country themselves. Not only was the war effort detracting from civil rights efforts at home, but it was directly disrupting the lives of families and individuals all over the country.

Most fundamentally, King felt that as a minister of the Christian faith and the proud winner of a Nobel Peace Prize, he had an obligation to fight against unjust violence globally. He needed to stand up for the masses of soldiers who’d been killed, as well as the masses of destitute Vietnamese.

Writing so many powerful addresses, Reverend King was a man of discipline. He stuck to nonviolent protest in spite of the incredible anger he must have felt as a Black man in segregated America. Most importantly, his nonviolent protests and leadership made for effective, lasting change across the country, setting an example for civil rights activists of the future.

Ω

Title Image: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, Washington, DC (Credit: Raffaele Nicolussi, via Unsplash)