For about 125 years, during the Ottoman Empire’s “Sultanate of Women,” women wielded unprecedented power.

◊

To a Western sensibility, stories of the love between a sultan and a harem girl must seem impossibly exotic. Western art, especially of the Romantic period, renders images of the medieval Middle East as fantasies of sexually objectified female bodies. These feminine subjects, depicted with neither agency nor personality, are activated and eroticized by the male gaze. In the paintings, these lithe women, dressed in diaphanous veils if at all, are viewed lasciviously by their male observers both within the borders of the paintings and beyond.

It’s therefore likely to come as a surprise to learn that, at least for a period of about 125 years, harems in Ottoman Turkey, and especially the one in the sultan’s residence, were centers of education and political power. In fact, some women in the harems were elevated to become individuals with great agency to define internal and international matters of state. These matters included diplomacy with Western rulers, domestic charitable programs, and even architectural building projects.

It would be a stretch to call the 16th and 17th centuries in the Ottoman Empire a period of feminist triumph, but within the boundaries of Islamic law and cultural tradition, women wielded unprecedented power in private and public arenas. It was a time called the “Sultanate of Women.”

Peek behind the curtains here and learn more about the role of harems in the Ottoman Empire.

The Rise of Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I, who became the sultan of the Ottomans in 1520, at the age of 26, inherited a vast empire from his father, Sultan Selim I. As was the custom of the time, at a young age Suleiman had moved from the center of the empire, Istanbul, to a provincial outpost where he ruled and was educated in the ways of the sultanate. He was accompanied by his mother, Hafsa, a concubine who would be elevated to the title of valide sultan, or mother of the sultan, once Suleiman succeeded his father.

At that time, the Ottoman Empire was a major world power, on par with England, under Queen Elizabeth I, and France, ruled by Catherine de’ Medici. The empire stretched from the Arabian Peninsula in the southeast to areas including northern Africa and southeastern Europe. Selim I was skilled in the arts of both war and diplomacy, expanding the empire with conquests in Persia and Egypt.

Suleiman learned well from his father. Once crowned as sultan, the son worked both to stabilize and to expand the breadth of the Ottoman Empire. Suleiman’s early years on the throne were characterized by ambitious campaigns that pushed Ottoman territory further into Europe, solidified control over the Mediterranean, and advanced the empire’s influence eastward as well. He became known not only as Suleiman the Magnificent, for the territories and wealth he added to the empire, but also as Suleiman the Lawgiver, for strengthening the empire’s governance and justice systems.

Life in the Ottoman Harem

One of the many “perks” Suleiman enjoyed as sultan was his harem. The harem was a private residence for women, their young children, and their servants. Unlike its depiction in many Western works of art and literature, however, it was neither a brothel nor a pleasure palace devoted to carnal delights. Within the cloistered walls of the harem, slave women, generally captured from conquered lands, were given a comfortable home to reside in. They received education in reading and writing, and they were not forced to become Muslim, although many of the concubines who provided children for the sultans did convert.

The traditional practice within the harem was that the sultan chose a woman to impregnate. After she gave birth, she was no longer of any importance to the sultan. If he so desired, he moved on to another concubine for his next child. This “one woman, one child” rule held sway in the Ottoman harems for centuries. If the child was male, he would be raised as Suleiman was, living in his father’s harem until he was of age, then relocating with his mother to a distant province, where he would become prince (in Western terms) until his father, the sultan, died.

After the death of the sultan, it was customary for the eldest son to become his successor. However, quite often, there would be intrigue – brothers (actually half-brothers) might take up arms against each other, and fratricide was common, even accepted. Rule of the empire would be ceded to the strongest, or the most adept at playing the lethal game of internal politics.

This romanticized idea of a Middle Eastern harem shows how the Western vision is both exoticized and eroticized. (Death of Sardanapalus by Eugène Delacroix, 1827. Collection of the Louvre, Paris, via Wikimedia Commons)

Luckily for Suleiman, Selim I had only one son, so when the father died in 1520, probably from natural causes, Suleiman was the sole heir.

Suleiman the Magnificent’s Taboo-Breaking Love for Hürrem, the Concubine

When Suleiman became sultan and moved into Istanbul’s New Palace, now known as Topkapi, it was expected that he would make good use of the harem and produce multiple male heirs to different concubines. At first, events progressed normally. Suleiman produced one son with one woman, then moved on to another concubine. But this is when the extraordinary happened. For the first time ever in the history of the sultanate, a sultan fell in love.

The woman Suleiman fell for was a slave girl who had been kidnapped at the age of 13 from a region of Eastern Europe located in what is now Ukraine. Her name at birth was Aleksandra, and it is said that her father was a priest in the Eastern Orthodox religion. Upon entering the harem, located in the Old Palace, in a different part of Istanbul from the sultan’s residence, she was renamed Hürrem, probably as a nickname, since it translates as “joyful” or “cheerful.” Reputedly, Hürrem lived up to those attributes.

In addition to the European women who were kidnapped and enslaved for the harem, scores of male African slaves were forcibly castrated and sent to guard the harems.

It was her lively personality, more than physical beauty, that apparently caused Suleiman to break all tradition and move her from the Old Palace harem to the New Palace, Suleiman’s home, which he expanded in size so as to make new space for Hürrem and scores of other concubines. But Suleiman treated Hürrem so differently, so lovingly, that it was rumored she had “bewitched” him.

Portrait of Hürrem, known as “Rossa” or “Roxelana” in the West (Royal Collection of Art of the United Kingdom, via Wikimedia Commons)

Breaking with all tradition, Hürrem was given the title haseki sultan, or “favorite of the sultan,” a title unheard of in Ottoman culture. Suleiman declared that Hürrem was henceforth his only female partner, and he was moved to write poetry to her in which he called her, “Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight / My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence.” He married her in 1533, consecrating the unprecedented arrangement.

Some historians suggest that Suleiman I may have had an intimate, possibly romantic relationship with his friend Ibrahim Pasha, with whom he shared private quarters and to whom he addressed poetry. Despite these signs of closeness, concrete evidence is limited.

Hürrem Establishes Her Power in Istanbul and Throughout the Empire

Overturning centuries of Ottoman custom, Hürrem gave Suleiman not one child, but at least six, five of them sons. He changed harem protocol for her; rather than sending her to a far-flung province with her first-born son, Mehmed, he kept her close to him. He installed her in his royal court, a position that no woman before her had held. And she was allowed to speak, to share her opinions, even if only behind a screen to hide her visage from the men of the court.

Hürrem blazed a trail for the women who would follow after her in the role of haseki sultan for later generations. She engaged in philanthropy with the Empire’s riches, founding a mosque complex in Istanbul (the Haseki Sultan Mosque), as well as hospitals, schools, and baths for both women and men.

She took a special interest in Jerusalem, which Suleiman’s father had conquered and added to the Empire in 1517. She founded a large soup kitchen there that served all religions – Muslims, Christians, and Jews – as well as the many who made pilgrimages to that historic town. She also supported the provision of lodging, water, and other services that made pilgrimage less arduous. Her work demonstrated a strategic understanding of the religious significance of Jerusalem within the empire.

Hürrem Creates a Lineage of Powerful Women

To secure her status and position, Hürrem bestowed courtly power upon her one daughter, Mihrimah, as well. She arranged for Mihrimah to marry a provincial governor, Rustem, and had him promoted to the title of grand vizier in Suleiman’s royal court. Ordinarily, the grand vizier’s power was second only to the sultan, but Hürrem remained number two in this exceptional circumstance.

Hürrem’s political savvy was apparent, too, in succession plans. Prior to encountering her, Suleiman had fathered a child, Mustafa. Despite his legitimate claim to the throne, Hürrem had Mustafa executed to clear the way for her eldest son, Mehmed, to ascend to become sultan when the time came. But Mehmed died of smallpox at 22, and Hürrem’s second-born son had died in infancy. Complicating matters were her three remaining sons: Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir. The youngest, Cihangir, was simple-minded from birth and never a serious contender for power, but Selim and Bayezid both coveted the throne and quarreled over succession.

Unfortunately for Bayezid, not only was he now second-in-line by virtue of age, but Hürrem made clear that she preferred his older brother, Selim. Bayezid and his progeny fled, hoping to survive the cut-throat customs of Ottoman royal successions. But Suleiman, apparently following Hürrem’s wishes, had them tracked down, and they were all assassinated.

Following Hürrem’s death in 1558 and Suleiman’s death at the age of 71 in 1566, Selim became Sultan Selim II and, following the new tradition established by his parents, selected from his harem the concubine Nurbanu, whom he named his haseki and wife, and empowered with a role in his court.

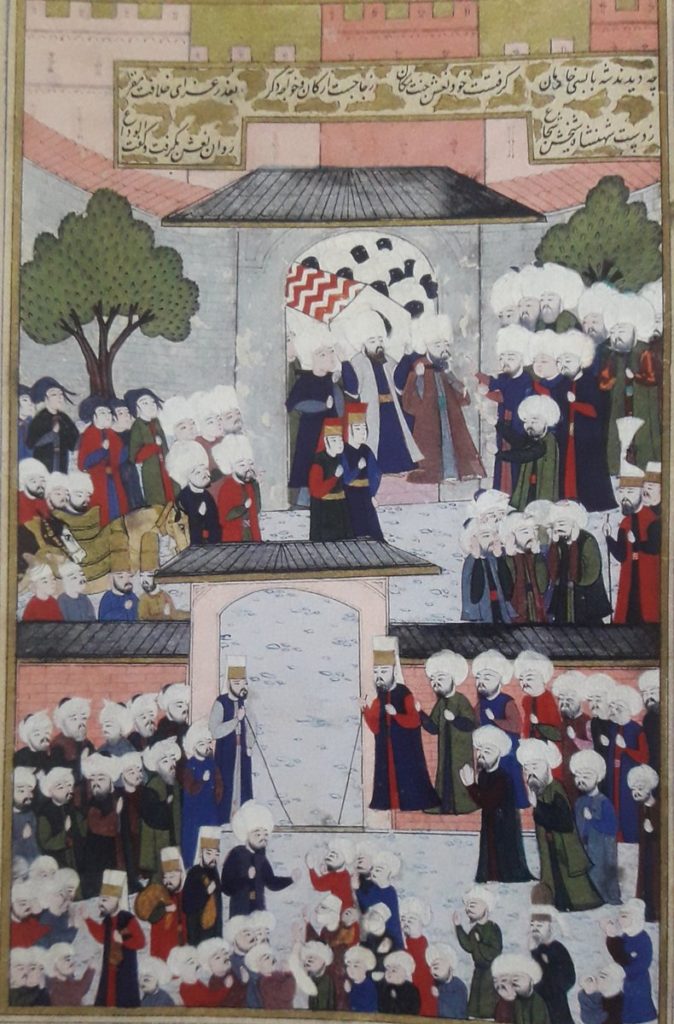

Nurbanu Sultan’s burial procession, a miniature by Nakka? Osman and his team, 1592 (Source: Topkapi Palace Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

Nurbanu was known for initiating a correspondence with England’s Queen Elizabeth I, and, if anything, was even more powerful than her predecessor, Hürrem. Like Hürrem, Nurbanu used her influence to benefit the common people of the sultanate, serving as benefactor to public works, including mosques. After the death of her husband in 1574, she became the valide sultan to her son Murad III.

After 125 Years, Backlash to Powerful Women Accompanies a Loss in Imperial Prestige

Murad III also married his haseki, Kösem, arguably the most powerful of all the women in the “Sultanate of Women.” Her political career spanned the reigns of multiple sultans, including her sons Murad IV and Ibrahim I, as well as her grandson Mehmed IV, for whom she served as regent. Her influence was so substantial that she ruled in effect as the empire’s de facto leader during several key regencies.

Kösem’s influence was cultural as well as political. She was known for her charitable work, including the construction of mosques, fountains, schools, and other public buildings across the empire. She established a large network to support the empire’s poor, frequently distributing food, clothing, and money to those in need. To fund various public works and maintain her charitable institutions after her death, Kösem created vakifs, which were similar to modern charitable foundations.

Incidentally, Kösem’s death came unexpectedly and violently. She was murdered, probably upon the order of her daughter-in-law, Turhan Sultan, who wanted control over her own son, Sultan Mehmed IV, and the empire. As valide to Mehmed IV, Turhan witnessed her power, and the power of women generally in the Ottoman Empire, being clawed back by men who were not only jealous but inclined to believe that women should return to silent positions in the sultan’s harem.

The Legacy of the ‘Sultanate of Women’

Turhan’s reign was marked by her support for military reform and her engagement in architectural projects, notably the completion of the construction of the Yeni Mosque in Istanbul, which became a symbol of her influence and legacy.

,_Galata_Bridge._Turkey,_Southeastern_Europe.jpg)

The Yeni Mosque in Istanbul (at right) remains one of the most notable acts of public benevolence by any of the haseki and valide sultans. (Source: Mstyslav Chernov, via Wikimedia Commons)

The “Sultanate of Women” period ended as the Ottoman court gradually reasserted male dominance over political affairs, beginning with reforms initiated by Grand Vizier Köprülü Mehmed Pasha in 1656. However, women left an indelible mark on the empire’s politics, culture, and society. It began as Suleiman the Magnificent proclaimed that love was more important than noble tradition, and it lasted until, in the next century, men of the royal court asserted that male power was more intrinsic to the life of the empire than any woman’s contribution.

It’s widely considered that the centuries following this era witnessed the gradual decline of the Ottoman Empire until its dissolution in the early 20th century. Whether this decline was due to – or in spite of – the “Sultanate of Women” is a question that remains to be pondered even now.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. A journalist and communications specialist for many years, he writes on various topics, including Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (City Lights) and resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Roxelane et Soliman le Magnifique (detail), attributed to Anton Hickel (Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

,_Roxelana_and_Suleiman_the_Magnificent.jpg)

,_Roxelana_and_Suleiman_the_Magnificent.jpg)