The little black dress is considered the epitome of elegance and class today, but its origin in domestic spheres is integral to understanding how this simple garment has become one of the world’s most talked about.

◊

Dressing myself has always felt like a chore – especially for occasions like office parties, weddings, or other formal events. The debacle of doing my hair, applying some makeup, and finding an appropriate outfit that comfortably fits my body is my definition of a nightmare.

I was 14 when my mother introduced me to the object that would streamline my closet and ease the stress of dressing: the little black dress. We went to the store and found a knee-length fit and flare dress with some white detailing. The occasion felt momentous – by wearing the iconic LBD, I was joining the likes of Audrey Hepburn, Princess Diana, and Marilyn Monroe. For a young teengager, having the dress felt like holding a milestone in my hands. To own one was to be inaugurated into a world defined by magazines and movies – where black dresses, heels, and makeup stood as markers of modern femininity.

Touted as a universal solution to the challenge of finding something to wear to evening galas, happy hours, and anything in between, the LBD in some form or another can be found in most every woman’s closet. It comes in more variations than any book or social media page could ever document – and that’s by design. Although the little black dress was canonized when Vogue magazine published one of Coco Chanel’s sketches, the garment is nothing new. In fact, the LBD has been a staple for working class women far longer than it has been a default garment for the fancier events in life.

Dig deeper into the life of one the world's fashion icons in MagellanTV's The Wars of Coco Chanel.

Black Dresses in Early Modern to Victorian Periods

Long before black dresses signified sophistication, femininity, and luxury, they were practical objects, although people in different classes had different uses for them. Worn by European upper class women for funerals, middle class women for work, and by working and lower class women as the only hand-me-down they could afford, the black dress was a practical garment. So, while the clothes a woman wore were used to cover the body, they also signified her socio-economic status.

The Labor Behind Early Dresses

Before the invention of the spinning jenny or the sewing machine, women wore dresses that were sewn together, dyed, and detailed with embellishments like lace, collars, and bows – for the upper classes, that is. For working class women, having seamstress skills in the early modern period was essential for refurbishing second-hand clothing, knitting socks for the winter, and repairing rips and tears to allow one set of clothing to last a while. Village tailors, often men, earned the business of upper class clientele looking to outsource the production of their clothing rather than make it themselves. But these artisans didn’t have free range in their designs or the materials they used for certain members of society.

La Dame Reformée (The Reformed Lady), depicting a French lady-in-waiting’s response to an edict about conservative dress (Credit: Rijksmuseum, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sumptuary Laws were used by many European countries between 1650 and 1800 to place limitations on what kinds of fashion people could wear. As French artisans were embracing exuberant designs with brightly colored silks, other nations imposed black dress codes to create a unique sense of identity, defined by modesty, religiosity, and uniformity.

Black clothing was worn by Spanish and Dutch elites who wanted to be depicted in portraits wearing black to indicate an air of seriousness, power, and national identity. At the same time, black had become an imposed uniform on everyday people who each owned about two to four sets of clothing and needed to look presentable despite how often they might need to wear something.

In the 17th century, the kingdom of Spain forbade people from selling or wearing dresses with silk trimmings, embroidered details, or any amount of gold and silver in order to create a universally understood idea of “dressing Spanish.”

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the number of people creating garments grew, thanks to the creation of new guilds in the fashion industry. The Parisian Maîtresses Couturières was established in 1675 by King Louis XIV, establishing the first group of independent seamstresses permitted to compete with male tailors whose guild protections years earlier had all but shut them out of the market.

Now, women could create designs for women’s and children’s clothing that could be bought by the expanding middle and upper classes who sought more showy and unique styles as their income increased. Working class women often inherited hand-me-down dresses from the families they worked for, and dresses of dark fabrics tended to have more longevity than white and intricately detailed pieces.

Seamstresses at work at a dress studio, 1947 (Credit: Erik Holmén, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Price of Dressing in Black

As the old adage goes, “dress for the job you want, not the job you have.” Though this might be more applicable in our current age of suits and name-branded everything, the expression reflects a truth of human psychology: If we want to be perceived a certain way, we should emulate the people whose power and lives we aspire to. The same was true for people in Victorian Europe. The elites who dressed in black had middle and lower class people wanting to look like them. While working class people were not wearing materially heavy silk dresses, they opted for black petticoats, cloaks, caps, and detachable sleeves.

One of the reasons the color black became symbolic of power in fashion was the intense – and costly – dyeing process required to make it. To create black for high quality materials, cloth could be dyed first in dark blue then submerged in a red madder bath. For a more affordable alternative, people could grind up wasp larvae found on oak leaves to create a rich, dark hue. Later, dyes made of logwood and ferrous sulfate would create the dye more easily, and the creation of a synthetic aniline black dye would eventually coincide with the invention of the sewing machine in the 1860s.

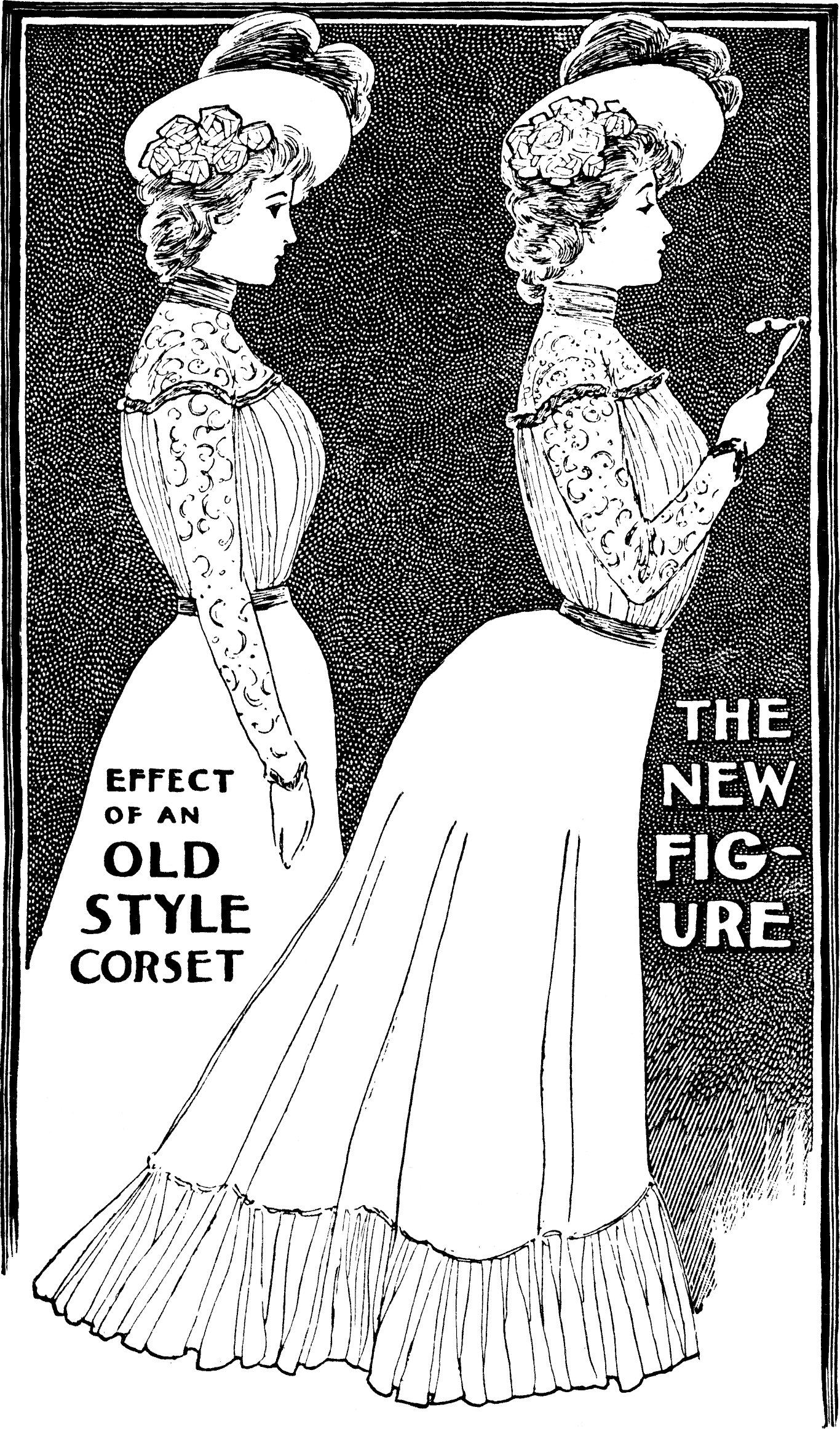

(Credit: Unknown Coronet Corset Co. work-for-hire artist, via Wikimedia Commons)

As the Industrial Revolution spurred a new era in garment design and sales, a more restrictive cultural trend re-emerged in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, even after sumptuary laws withered away. Corsets, bustles, starched petticoats and a heap of silk fabrics became in vogue. These undergarments reshaped womens’ physical appearance and internal organ configurations to improve their posture, shrink their waists, and accentuate their chests. The tight-laced corsets and pounds of fabric restricted women’s movements from side to side and hindered their ability to sit down. But the structured, demure demands of women’s clothing were to be entirely disrupted in the coming decades.

Turn of the Century Fashion Revolution

In the lead-up to the year 1900, women’s fashion could be divided into two echelons: fashion and working class women’s attire. Upper class womens’ fashion was designed, often by men, for them to engage in high society and often involved several outfit changes throughout the day. That way women could engage in movements like sitting, being outdoors, and eating without compromising how they looked to others. Working class women wore discarded clothing from upper class women, but this sometimes led to confusion and blurring of class lines. Consequently, maids were often made to wear only black dresses, a mob cap, and an apron to avoid any chance of confusion. To upper class women, black dresses came to be seen as “dressing down.”

Photo by A. Thuret, one a number of postcards by the photographer (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Chanel Adapts Working Class Garments for Haute Couture

Iconic fashion designer Coco Chanel engaged with the pret-à-porter notion of modern fashion in which people could purchase pre-made garments that generally fit their size. But her creations turned traditional notions of the black dress on their head. Having grown up impoverished before ascending to international acclaim, Chanel had a unique perspective dramatically eclipsing class divides in her own life. The juxtaposition of poverty and luxury would go on to define her vision as an artist. A pivotal experience not just for Chanel but the history of the fashion industry was the time she spent as a shopgirl.

For even more on Coco Chanel, check out The Designers on MagellanTV.

The identity of being a shopgirl was a revelation for what it meant to be a working class, independent woman. Finding employment in a department store offered young women the opportunity to leave rural communities, make a decent living, and have life experiences traditionally reserved for the upper echelons of society. By serving well-to-do women with their knowledge of the latest in fashion trends, shopgirls were still in service positions, but they were now an intermediary in an exciting but vulnerable space for women to find garments that fit and looked good. Shopgirls tended to spend their paychecks on clothing from the stores they worked in, once again blurring the lines of what working and upper class women looked like. Again, to curtail the muddling of class fashions, shopgirls, like their mothers and grandmothers who were maids, were once more assigned a uniform – the lowly black dress.

During this time, France dominated fashion, and Coco Chanel’s boundary-breaking designs played a huge role in that. After creating connections in high society, Chanel received financial support to sell women’s sportswear and jersey sweaters that emphasized elegant comfort over the exhausting corset-styles that were still the mode. Women flocked to purchase her designs, and, with the rollout of Chanel No. 5 perfume in 1921, she also changed the fragrance industry and emerged as a preeminent force of fashion and design.

1958 Coco Chanel strapless evening dress, black lace with velvet sash (Credit: Rhode Island School of Design Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

When her sketch of the memorable little black dress appeared in Vogue magazine, fashion aficionados marveled at the universality of the idea. Some of her early designs were made of satin, featured premium lace designs and highlighted pearl jewelry. In the wake of World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic, purveyors of her creations had become accustomed to thinking of black dresses being reserved for funerals. Reappropriating the color for the aesthetic of a kind of luxurious poverty, the little black dress gave wearers an outlet to defy convention while still indulging in the quality materials and expensive accessories that accompany haute couture.

Chanel’s LBD was called the “Fashion Ford,” which, like the Ford automobile, had universal appeal and accessibility, and took over a huge segment of the consumer market.

Chanel’s design had a shorter hem, drawing on the flapper dress design associated with the suffrage movements across Europe and the U.S. in the early 20th century. Her loose-fitting, short dress marked a notable shift, emphasizing comfort and movement over the restrictive ensembles that had been created by men for women for generations prior. The architecture of the dress played into womens’ natural curvature, and the black color helped create a silhouette while not drawing too much attention to a woman’s body shape. The LBD elevated the color black back into power. Rather than exuding piety and uniformity, it spoke to individuality, politics, and sexuality.

The Little Black Dress Today

In the decades following publication of the ground-breaking LBD drawing, other designers, notably Christian Dior, recognized the popularity of Chanel’s design and created alternatives that pushed back against some of her changes. “The New Look” that Dior created re-emphasized cinched waists and highly-tailored outfits. A few years later, Dior published The Little Dictionary of Fashion and wrote that the color black was acceptable to wear at any time for any occasion. Fashion publications and magazines played a huge role in determining what style trends would catch on among the masses, and, almost universally, the LBD was in and here to stay.

During the World War II, Chanel is suspected to have been a Nazi informant, and relocated to Switzerland after the German occupation of France ended. Recently unearthed documents claim that Chanel worked for the French Resistance, but historians contest these finds.

In the 1950s, the LBD became a staple of cocktail hours and events hosted by housewives. Women breaking the glass ceiling and foraying into white-collar jobs tended toward more formal, colorful outfits that conveyed professionalism and femininity, but didn’t go so far as to bring the LBD into a man’s workplace.

The LBD remains a uniform for many women in service jobs, particularly in department stores. There, they sell purses and perfumes bearing the name of the woman who once walked in their shoes, before raising their lifestyle to an aesthetic.

Today, I keep a little black dress in my closet for the occasional work function or nice restaurant outing. But the mystique it once had has faded for me, as I associate it with situations where I feel I have to wear one just to blend in. The LBD these days seems to come with the weight of a deep, complicated history hanging from my shoulders – but then again, maybe I just need something to wear.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV and freelancer. Originally from Georgia, she went to college to study philosophy and studio art. She now works in Chicago as a media relations coordinator.

Title Image: Adobe Stock image