In spring, new life literally springs up everywhere – flowers bloom, birds chirp, and buds burst. Across the globe, spring festivals bolster our revitalized spirit – with common themes that celebrate new beginnings and ancestral values.

◊

No matter our culture or background, we view spring as an opportunity to start anew. At the same time, we treasure our traditions. We remember the significance of age-old stories, enjoy our favorite meals, and strengthen relationships with family and friends.

Invariably, there are eggs – the ubiquitous symbol of new life. And vibrant colors are everywhere – in dyes, flowers, and foods – bringing the promise of harmony and hope for a better future.

For more on the Quingming festival, check out the "Ancestors" episode of the MagellanTV series Celebration Nation.

Qingming: Connecting with the Past

When winter’s cold weather finally subsides, we may get the urge to do some “spring cleaning” – a yearly chore that many of us would rather avoid. But if you’re Chinese, the Qingming Festival – Tomb-Sweeping Day – is an important family time filled with significance. A public holiday in mainland China, this ancient tradition is observed by the Chinese across Asia and around the world.

Qingming – meaning “brightness” or “purity” – is a time set aside for families to come together to refurbish the graves of their ancestors. They give their late relatives’ gravesites solemn respect by pulling weeds, sweeping and polishing the monuments, and planting or placing fresh flowers. With reverence, they burn incense and offer special foods – such as sweet green rice balls (qingtuan) or rice dumplings – ending with a final wine toast.

Qingtuan is the traditional Chinese food of the Qingming festival. (Source Wikimedia Commons)

Once the serious tasks are done, families also fly kites, set off firecrackers, and have picnics. Boiled eggs, often painted, are a common snack. A traditional Qingming food for the Zhuang people is five-color steamed glutinous rice – green, red, purple, yellow and white – the colors made using juices of various plants. Signifying a good harvest, this dish is believed to bring fertility and good luck. Shanxi Province is known for its Qingming steamed Zitui buns, commonly made in the shape of rabbits and other animals.

Qingming is often celebrated for several days, while some rural observances can last for ten days on either side of the actual date. Rites like these bring people together not only to strengthen familial bonds but also to practice cultural customs, carrying cherished rituals from one generation to the next.

Passover: Rejoicing in Freedom

For Jews, a different sort of spring cleaning is associated with Pesach – that is, Passover – an eight-days-long holiday. Before Pesach begins, it’s important to remove every bit of chametz (leaven) from the household. Anything made from wheat, oats, rye, barley, or spelt must go – so all flour, cookies, cake, pasta, and breads must be removed. Leaven is eliminated because when the Israelites escaped slavery – recounted in the Bible’s book of Exodus (Chapters 1–18) – they didn’t have time for their bread to rise.

Pesach is a time for the generations to come together to retell the Exodus narrative in which God called upon Moses to appeal to the Egyptian Pharaoh to free the enslaved Israelites. Jews remember this story of freedom during a seder – a meal normally held in Jewish homes on the first night, and sometimes as a community on the second night.

A seder plate (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Favorite foods include brisket, potatoes, and matzo ball soup. There is also the Seder Plate, displaying ceremonial foods that symbolize various aspects of the Exodus story: a shankbone (the sacrificial lamb), bitter herbs (for the harshness of slavery), charoset (a nut-and-fruit mixture representing the mortar used to build the pyramids), matzo (unleavened bread), salt water (for tears), parsley (denoting renewal), and a boiled egg (indicating new life).

During the seder, there are readings from a prayer book called the Haggadah. There are questions and answers, songs, and sometimes dancing. Throughout, there are four wine toasts, each one a “cup of blessing.” At some point, the afikomen – a broken piece of matzo – is hidden. After the meal, children are challenged to look for it, and whoever finds it wins a prize, usually money or chocolate.

Seders are as diverse as the people who host them. Individuals find meaning in connecting elements of the Passover story to their personal lives and to their local communities. In some, there may be an emphasis on the connection between the experience of the Israelites in slavery and that of other groups, such as African Americans, in their history. Others may take a more personal approach, with participants invited to examine ways that they are “enslaved” to whatever is no longer needed in their lives.

The joy of Jewish children scrambling to find the afikomen to win a prize is similar to the Christians’ Easter egg hunt.

Children compare their Easter egg finds. (Credit: Eren Li via Pexels)

Easter: Forgiveness of Sins

Christians worldwide observe Easter Sunday on a date that shifts according to the Gregorian calendar – and although not always aligned with Passover, Easter is a holiday forever connected to it.

As told in the Bible’s Gospels, Jesus (Yeshua in Hebrew) was a popular 1st century rabbi in Roman-occupied Palestine who gathered followers inspired by his teachings and healings. His popularity not only upset the Jewish leaders’ status quo, but also the rulers of the Roman Empire, who viewed him as an agitator.

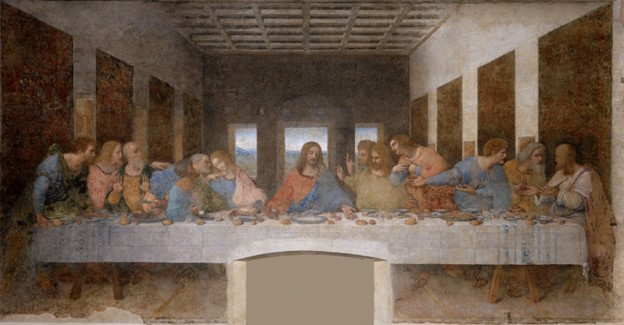

As Passover approached, Jesus realized that his arrest and execution were inevitable, but he still decided to get together with his closest disciples for the seder – which Christians today call The Last Supper. Jesus picked up a matzo and called it his body, and when he blessed the fourth cup of wine, he called it his blood. Down the centuries, this ritual became what Christians now call communion.

"The Last Supper" (1495-1498) by Leonardo da Vinci (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy)

The method of capital punishment in those days was crucifixion, the gruesome practice of nailing a person to a wooden cross. Jesus was ordered to be arrested and flogged by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, and condemned to death.

The day Jesus died on the cross is called Good Friday. As the story goes, he rose from the dead on Sunday, proving that he was the Messiah (the Christ, that is, the “anointed one”) – the savior whom the Jews had been longing for. Those Jews who believed in Jesus’s resurrection followed his teachings, and many years later started calling themselves Christians. (And that’s another story.) Those who were crushed by Jesus’s death, not convinced that he had risen – he was just another failed messiah – continued on as Jews.

Borrowing from the Jews

Easter is the holiest day for Christians. But what about all the customs that grew up around it? First, we have to go back to Exodus: Toward the end of the biblical account, at the point when Pharaoh still stubbornly refused to free the slaves, God instructed Moses to tell each Israelite family to slaughter a lamb, and smear its blood above the door, as a sign telling God to “pass over” (that is, pesach) their household that night, sparing everyone inside. All the Egyptian first-born sons, on the other hand, were killed due to Pharaoh’s unwillingness to let the people go. When Pharaoh lost his own son, that was the last straw, and finally he relented.

Christianity took the idea of Passover’s sacrificial lamb, calling Jesus the “Lamb of God” who through his death brought salvation to all, cleansing humanity of sin. That’s the complicated reason why the lamb is both a Passover and a Christian symbol.

The Latin word for Easter, Pascha, comes directly from the Hebrew. And that’s why Romance languages all have a related word for Easter, e.g., Spanish is Pascua, Italian is Pasqua, French is Pâques, and Portuguese is Páscoa.

In many places, especially in Europe and Latin America, Holy Week – beginning with Palm Sunday and ending with Easter Sunday – can be an elaborate observance that includes processions and rituals in which individuals sometimes reenact scenes from the last week of Jesus’s life leading up to the resurrection. Some people carry crosses through the streets; some even self-flagellate as a form of atonement for wrongdoing.

(Credit: Gerd Altmann via Pixabay)

Eggs, Birds, and Bunnies

The word Easter comes from the Old English Eostre, an early German word for “dawn” and also the name of an ancient Northern European fertility goddess. The rabbit, because of its exceptional reproductive capabilities, became a symbol associated with spring.

The concept of the Easter Bunny came on the heels of Lutheran egg hunts, when Germans added a legend about an Osterhase (“Easter hare”) who left colored eggs in gardens for children to find. German immigrants brought this folklore to America during the 1700s. Easter baskets resemble birds’ nests.

For more than 100 years in Zenica, Bosnia, Cimburijada – the Festival of Scrambled Eggs – has marked the first day of spring. Starting at sunrise, a scrambled egg breakfast is cooked in a gigantic caldron and served to all comers.

In Lithuania, the country’s national bird’s traditional spring return happens on Stork Day, every March 25th. Also called Children’s Day, the white storks are said to secretly bring gifts to children, leaving sweets and colored eggs on tree branches and fences. The fable about storks delivering newborns still persists. And if a stork nests on your property, you’re sure to have a harmonious year.

Ramadan: Fasting as a Time of Renewal

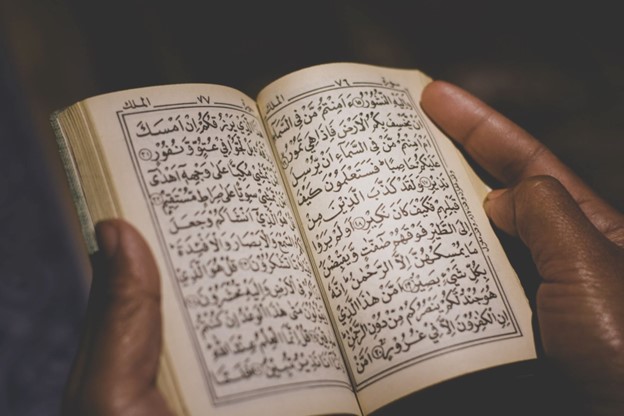

The Holy Qur’an (Credit: Fauzan My via Pixabay)

Although not typically coinciding with spring, Ramadan is a month-long holiday Muslims worldwide commemorate according to their shifting calendar – and in the year this article is being written, their observance starts in March. Fasting daily (with special foods eaten before sunrise and after sundown), dedicated Muslims take this time for prayer and introspection, focusing on bodily cleansing as well as cleaning up one’s behavior.

Ramadan means “scorching heat” in Arabic. Just as the blazing sun evaporates water, the practice of Ramadan symbolically burns away sins, purifying and molding believers into better human beings.

Considered Muslims’ holiest time of the year, Ramadan points to when the prophet Muhammad received the revelations of the Qur’an (in 610 CE). The angel Jibril (Gabriel) imparted wisdom from Allah (God), explaining that He is the only God. Allah had sent prophets to Earth before – bringing the teachings of Judaism and Christianity to humanity through Nuh (Noah), Ibrahim (Abraham), Musa (Moses) and Isa (Jesus). Now Muhammad was to be Allah’s final prophet, bringing the message of oneness to all.

Holi: A Festival that Colors Everything

India’s national spring holiday is the Hindi festival of Holi. The night before, people light bonfires and ceremoniously release wrongdoing, vowing to start again with a clean slate. On Holi, also called the Festival of Colors, people drench each other in colored powders and waters.

(Credit: Sonu Agvan via Unsplash)

The practice comes from a legendary romance as told in the Vedas. Krishna (an incarnation of Lord Vishnu), while staying with the cowherds of Vrindavan, became smitten with Radha (an incarnation of the goddess Lakshmi), who was living as a milkmaid. Krishna had blue skin and Radha had a fair complexion. While playing a spirited game, Krishna smeared color on Radha’s face so she would look like him. After that, she was his constant companion.

If you’re in public on Holi, you’re fair game to be pummeled with pigment. Everyone participates – regardless of status, age, gender, or occupation. Holi is the ideal equalizer. Not only does the day honor a tale of undying divine love, it aims for equality and harmony – with a generous sense of fun for all.

These are mere glimpses into just a handful of spring celebrations. There are countless colorful festivals to explore – such as Japan’s Hanami (The Cherry Blossom Festival), Nowruz in Central Asia and the Middle East, Las Fallas in Spain, Egypt’s Sham El-Nessim, and Thailand’s Songkran.

What does yours look like?

Ω

A published author and editor since 1983, Janis Hunt Johnson founded Ask Janis Editorial in 1994. Residing in southern Oregon by way of Chicago and L.A., she loves to travel and learn new things – while writing about culture, the arts, and resilience. She also writes an interfaith spirituality blog on Medium.

Title image credit: Ray Hennessy via Unsplash