The framers of the U.S. Constitution walked a narrow path between slavery and antislavery in its writing. Its compromises threatened the Republic’s survival.

◊

The Civil War was an American catastrophe of unequaled proportions. Never before or since has one set of states risen in armed revolt against another. Where did this rift start? Many instances through the 19th century qualify as steps toward the schism. However, let’s take a look at a date in the 18th century some political theorists point to as the moment that started an irreversible course toward secession: 1787. It was in this year that the U.S. Constitution, through debate and discussion, was composed.

For an examination of the slaveholders who wrote “We the People” into the U.S. Constitution, view Liberty & Slavery.

A Compromised Constitution

One of the Constitution’s significant shortcomings was its failure to decisively address the issue of slavery. This indecision stemmed from the need to reconcile the starkly divergent views held by slave-holding Southern states and the more abolitionist-inclined Northern states.

The Constitution does not specifically condone slavery. However, the presumption in three key passages was that slavery was constitutional and that slaves possessed no rights of American citizenship until the 13th Amendment abolished the practice in December 1865. Because of these passages, the Constitution allowed slavery to grow and flourish, especially on farms and plantations, through the end of the 18th and into the 19th century.

Approximately 25 of the 55 delegates who signed the U.S. Constitution were slave owners, notably including George Washington, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton.

These passages are well-known to Constitutional scholars; they are referred to as the “Three-fifths Compromise,” the “Fugitive Slave Clause,” and the “Slave Trade Compromise.” Following is an overview of the significance of each of these sections.

The Three-fifths Compromise

Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution states: “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.”

In modern English, this means that three-fifths of the enslaved population were to be counted for both taxation and representation purposes. It gave Southern states disproportionate political power in the House of Representatives without acknowledging the full personhood of enslaved individuals. This agreement allowed the enslavement of Black people to spread.

The Fugitive Slave Clause

Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution reads, “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.” Note that there is no mention of the term “slave” in this passage, while slavery and indentured servitude were quite clearly the topic.

_-_series.jpg)

Slavery in the United States, 1837, by Charles Ball (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

This clause ensured that slavery’s reach extended into all states. It exacerbated tensions between Northern states, where abolitionist sentiment was rising fast, and Southern states, where slave labor was built into each state’s agrarian economic system.

The Slave Trade Compromise

Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution states: “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.” Note again the conspicuous absence of the term “slave.”

This clause prohibited Congress from banning the importation of slaves before the year 1808. The text allowed the transatlantic slave trade to continue unabated for 30 years from the ratification of the Constitution. The delay was a concession to Southern states, which were dependent on the continued importation of enslaved Africans.

Naturally, this set up a showdown between the abolitionist movement in the North and the slaveholders in the South. This move, which these days is called “kicking it down the road,” foreshadowed the many arguments and disagreements that would grow steadily in the early 19th century.

Congress did, in fact, pass the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves to take effect on January 1, 1808. While it did not end slavery, it put pressure on Southern states, which eventually led to the opening shots of the Civil War in 1861.

Second Thoughts on Slavery from America’s Founding Fathers

Several Constitution signers who held slaves later changed their minds and aligned with the thinking of the abolitionist groups, which were growing in size and influence in the “free” states in the North. These individuals, including Benjamin Franklin, highlight the complex and evolving attitudes toward slavery among several Founding Fathers.

Franklin was not alone – others who had second thoughts about slavery in the U.S. included George Read of Delaware and James Wilson of Pennsylvania. But Ben Franklin’s reversal was emblematic of the shift in attitudes of the Founding Fathers and other Americans who rethought their earlier convictions, freed their own slaves, and became outspoken on the status of Black people.

While James Wilson did not oppose slavery in 1788, his later judicial opinions reflected an antislavery stance, particularly through his service on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. And George Read, although initially a slaveholder, manumitted his slaves and supported gradual emancipation in Delaware.

The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840 painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon (Source: National Portrait Gallery, London)

The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840 painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon (Source: National Portrait Gallery, London)

But it was Franklin whose shift was most dramatic (or, at least, best known). Initially, Franklin owned slaves who worked in his household and print shop. He even published advertisements for the sale of slaves in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, a common facet of the slave trade.

However, Franklin eventually became an admirer of Enlightenment ideas, and he was increasingly influenced by them while serving as the American ambassador to France from 1776 to 1785. He began to rethink the morality of slavery and saw the contradiction between America’s fight for liberty and the existence of slavery. By 1781, he no longer possessed slaves.

Franklin joined the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage in 1787, later serving as its president. This society was one of the first abolitionist organizations in America. In 1789, Franklin petitioned Congress to end slavery and the slave trade, citing both moral and economic arguments against the institution. This petition was one of his last public acts before his death in 1790.

These signatories were not alone in the evolution of their views. Although Southerners were tied to slavery for their economic survival and their wealth, the institution was held in increasing disdain in the decades following the ratification of the Constitution. This began to deepen the divide between pro-slavery and antislavery forces in the United States, which ultimately led to the Civil War.

The Gradual Shifts Leading to Secession

What’s really surprising to many is that it took as long as it did for the South to rise against the North. Building on the Constitution’s Fugitive Slave Clause, legislators, with a strong push from the South, passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1793. This law mandated the return of escaped enslaved people to their owners and imposed penalties on anyone who aided in their escape. It also intensified conflicts between free and slave states.

Then, in 1807, Northern members of Congress passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, which was promoted and signed into law by President Thomas Jefferson, himself a Southerner and slave owner. This move further exacerbated grievances in the South, where it was viewed as an infringement of the right to use slave labor to run plantations and keep its agrarian nature operational.

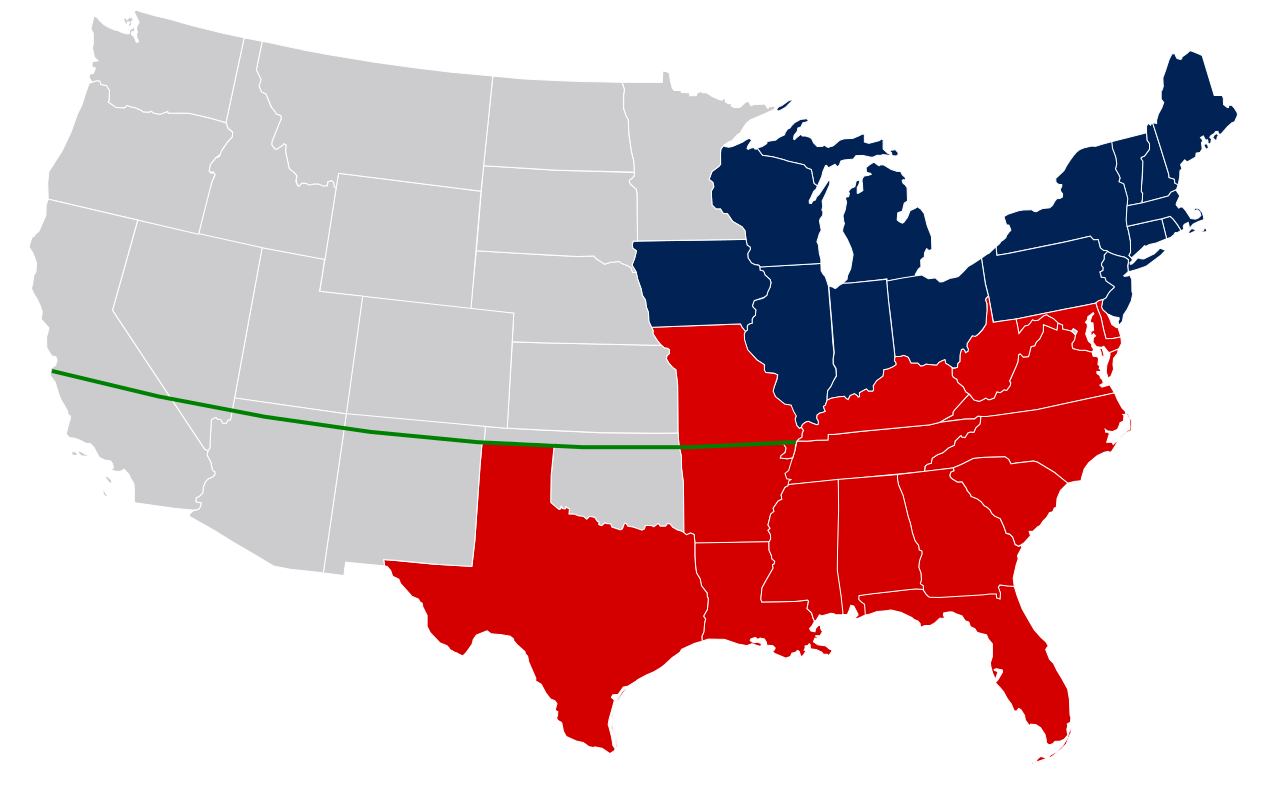

Compromises continued further into the 19th century. For example, in 1820, the controversial Missouri Compromise was passed. This law admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state to maintain the balance of power in Congress. It also prohibited slavery in the expansive Louisiana Territory north of the 36°30′ parallel. The line demarcated the southern border of the Oklahoma Panhandle, the northern border of Arkansas, the northern boundary of Tennessee, and the northern boundary of Missouri’s Bootheel region.

Map of the Missouri Compromise’s boundary lines (Source: Tintazul: Júlio Reis, via Wikimedia Commons)

Map of the Missouri Compromise’s boundary lines (Source: Tintazul: Júlio Reis, via Wikimedia Commons)

This deal was an early indication of the regional divide over the expansion of slavery. Many worried, rightly, that the U.S. was now lawfully divided along slavery and abolitionist lines. The North held this decision against the South and saw itself increasingly as a refuge for escapees who arrived on the Underground Railroad.

Significantly, the Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision in 1857 acted as yet another critical stepping stone toward the Civil War. The ruling stated that slave Dred Scott was not an American citizen and had no standing in court to sue for his freedom. Further, the Court declared that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories, effectively nullifying the Missouri Compromise. The ruling was celebrated in the South, while it outraged the North. This polarization set the stage for the Civil War.

Battle Lines Were Drawn

The stark lines between the defense of slavery and the increasing revulsion it provoked were firmly in place by the time the Constitution was ratified. Its framers were only able to form a nation through grave and regrettable compromises, but even that process was fraught from the beginning. It took only Lincoln’s immortal “four score and seven years” for the once-unified country to split apart.

Even now, remnants of those divisions live on in different but not entirely distinct forms. We all hope for the continuing success of the American experiment in democratic government, which insists that all citizens are equal under the law. But, as Founding Father Thomas Jefferson so aptly stated in 1834, “the price of liberty is eternal vigilance.”

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. A journalist and communications specialist for many years, he writes on various topics, including Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (City Lights) and resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Scene at the Signing of the Constitution (detail), painting by Howard Chandler Christy (1940), hung in the East Stairway, House of Representatives wing, U.S. Capitol. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)