Over 11 percent of Americans – almost 40 million people – live in poverty. What, exactly, does that mean?

◊

It’s a strange phrase: the cost of living. A cost, in monetary terms, is the price of something. So, is “the price of living” better? That sounds even more peculiar. “Cost” also means loss or penalty. The loss of living? The penalty of living? Ouch. When we stop to think about this common phrase, things become curiouser and curiouser, indeed! Let’s go down that rabbit hole.

One wouldn’t think you have to give something in order to live, yet unless others are going to wait on you hand and foot, you’ll have to do something to stay alive. For much of the world’s population, the days of hunting and gathering, growing crops, and practicing animal husbandry are long gone. We go to grocery stores and farmers’ markets. We stock up on household items at big box stores – though maybe we grow some herbs in small planters positioned carefully in the sunlight.

The place where you put that planter or store those household items costs, as well. A shelter of some sort is also part of that staying alive stuff. What else? Well, the MagellanTV subscription and other goods and services that make life better cost, but aren’t among life’s bare necessities, right?

Follow five American families trying to get by on minimum wage in this hard-hitting MagellanTV series.

The (Bare?) Necessities of Life

According to the United States Bureau of Labor, the average cost of housing in 2023 was just over $24,000. That amount sometimes includes utilities for renters, not homeowners. But food and other groceries, transportation, health care, clothing, and other essentials for daily life mean the annual cost of living adds up.

In the United States, the Cost of Living Index (COLI) is calculated by comparing the price levels of goods and services (daily living expenses) in various geographical areas. The national average is called the base, which is set at 100. So, if you compare the COLI for a given state, you can see the comparable living costs. In 2023, for example, Mississippi scored an 86.2, which means the cost of living is lower than the national average. Got it, but how does that play out in daily dollars for the average person?

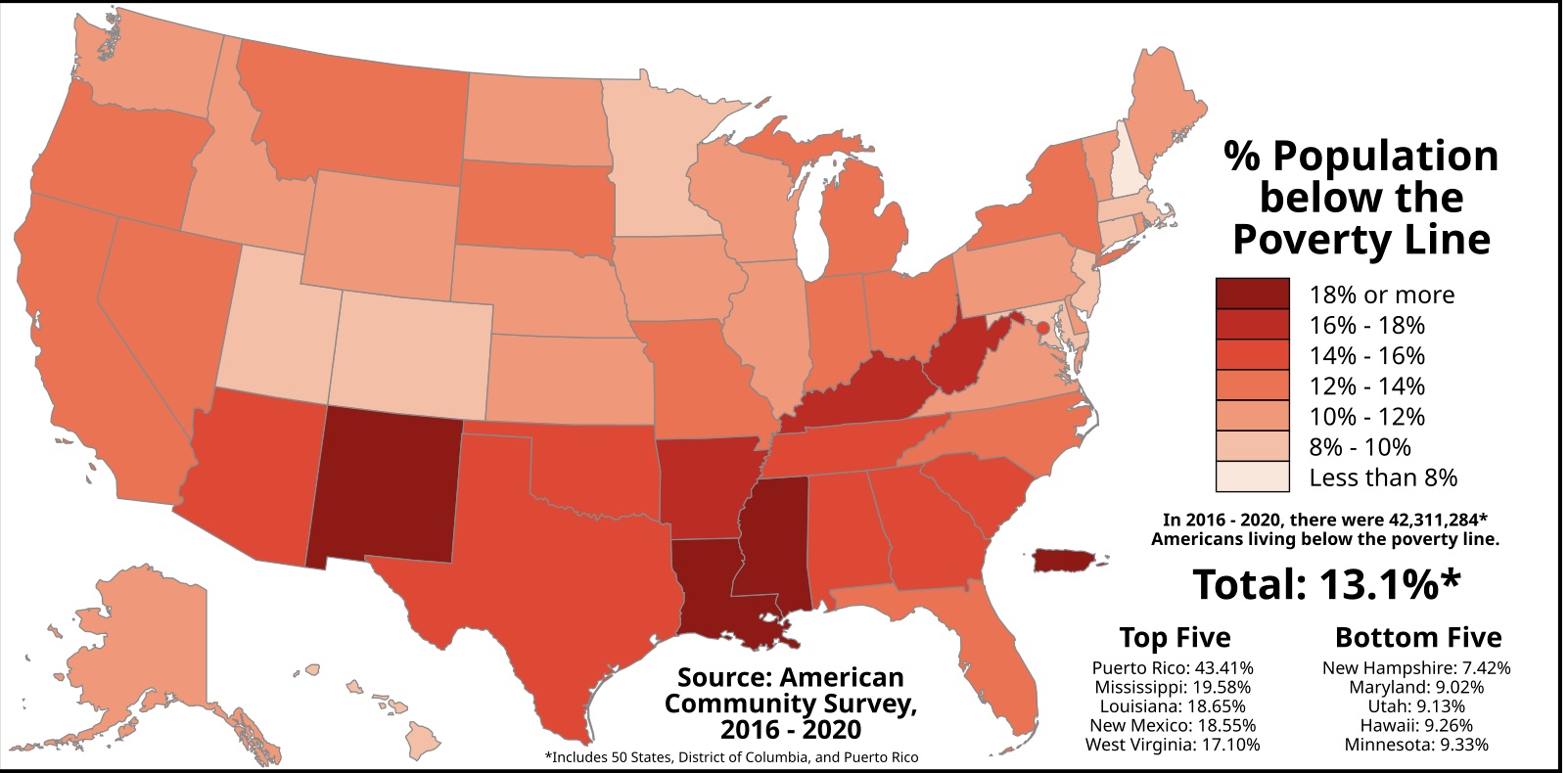

For comparison, here are the U.S. Bureau of Labor Stats, 2016-2020

For comparison, here are the U.S. Bureau of Labor Stats, 2016-2020

The U.S. Bureau of Labor determined the cost of living in 2023 totaled just over $77,000, the bulk of which went to the following necessities: housing (33%), transportation (17%), food (13%), personal insurance and pensions (12%), and healthcare (8%).

Necessities. What are they? Do “the basic necessities” – shelter, food, water, clothing, and medical care – really constitute what we need to live? And who decides? Consider, for example, the consequences of skyrocketing housing costs without corresponding increases in the federal minimum wage, which has stagnated since 2009, not to mention the limited investment in psychiatric and psychological health. Although these are not the only explanations for homelessness, the fact remains that, in 2023, more than a half-million people were homeless in the United States.

According to the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, underfunding programs that make housing affordable, systemic failures like mass incarceration, along with inadequate safety nets and healthcare, are among the reasons for today’s increases in homelessness.

In most societies, the necessities include transportation and the requirement for food and water is expanded to include safe shelter, adequate food, potable water, clean air, quality medical care, and a good education. There are plenty of people who don’t have that standard of living. Depending on where they live and how poor they are, they get by on far, far less than those who can casually wander the grocery aisles looking for the wine that will pair perfectly with tonight’s entree.

When it comes to poverty and a standard of living, necessity is . . . squishy. I mean, I know I don’t need to drink coffee or beer to stay alive, but they sure do improve my quality of life to the point where I’d be pretty bereft without either. But let’s suppose I had to give them up, along with my monthly charitable donations, yoga classes, and eating out at least once a month. Does that mean I’d be . . . poor? Of course not! On the other hand, it should be clear that people who have to choose between paying for medications or utilities is not facing a mere standard of living trade-off.

Global and U.S. Poverty Rates

According to the World Bank, which updated its global poverty lines in 2022, “extreme poverty” occurs when one person exists on $2.15 a day. Two dollars and fifteen cents! Per day!

How does anyone live on that? Not that you need it, but for contrast, the income of the world’s richest person, Elon Musk, averages more than $9,000,000 a day. Nine million. A day. (I suppose a related question is why anyone would want to be that rich, but that’s another article for another time.) As of October 2024, the World Bank counted almost 700 million people living in extreme poverty globally. That’s just over 8.5 percent of the world’s population.

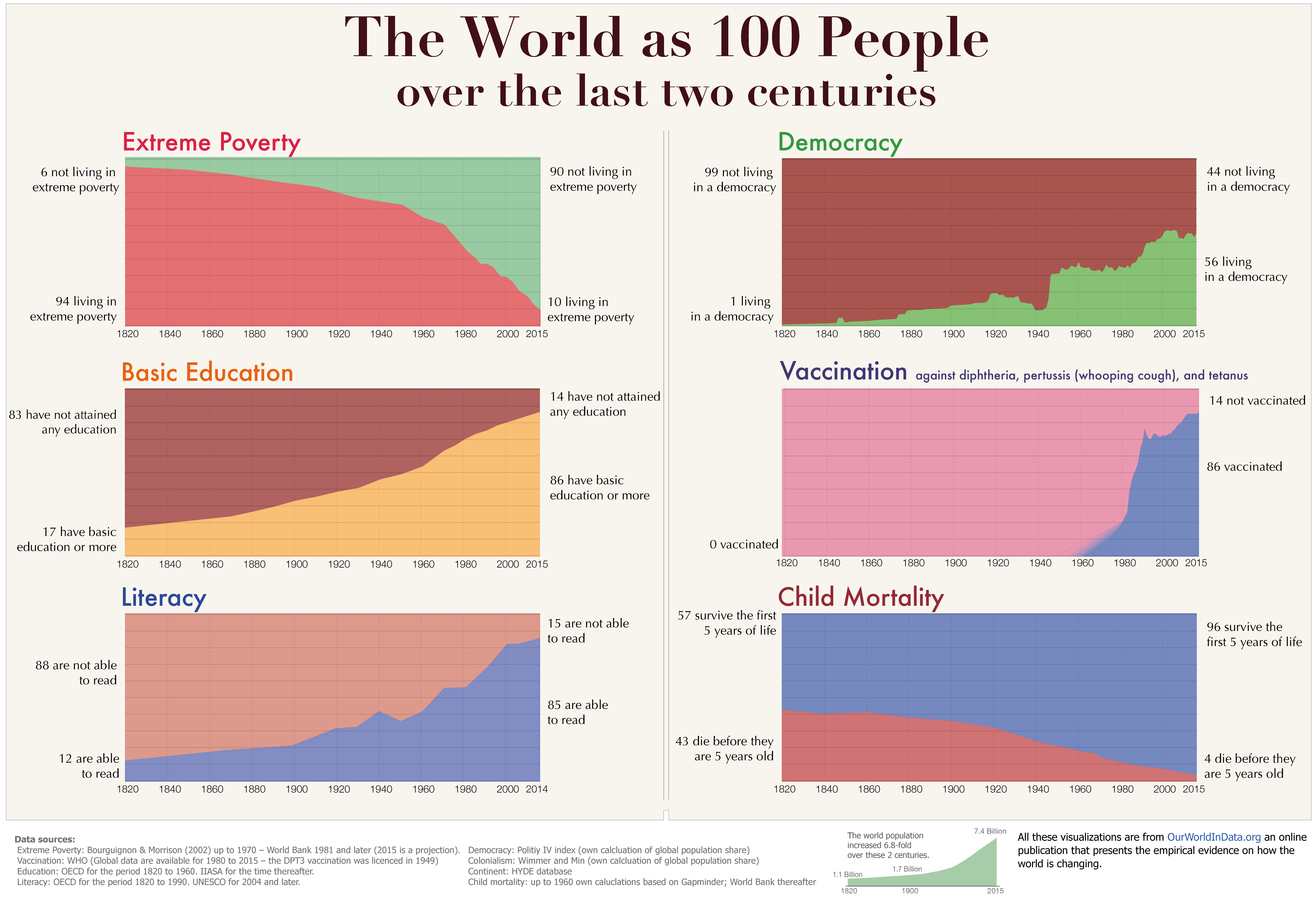

Thinking about issues around the world in terms of 100 people (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Thinking about issues around the world in terms of 100 people (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The U.S. Census Bureau uses the Official Poverty Measure (OPM) to determine the poverty line. Originally developed by a staff economist at the Social Security Administration in the mid-1960s, the OPM determined the poverty threshold by multiplying the cost of “a minimum food diet” by three. That multiplier stood for “other family expenses.” Refined and extended in 1964, federal agencies began using the formula.

The Census Bureau set the poverty level for an individual at $15,480 in 2023. At the time, 36.8 million people in the U.S. lived in poverty. So, as we’ve seen, those millions of Americans must scrape by with less than enough annual income to rent the average apartment. Of course, that’s more than the global extreme poverty threshold of $2.15 per day, but that’s hardly heartening to folks who are struggling just to survive.

In 2023, 16 percent of the U.S. population living in poverty in the contiguous United States were under 18 years old – around 52 million children. So, let’s suppose a two-person household consisting of a parent and child. The 2023 Federal Poverty Level (FPL) was $14,580 in the contiguous United States. (It was raised to a whopping $15,060 for 2024.) There’s no way a single parent can pay for the cost of living on an income that amounts to $20 a day, per person. So, government-funded programs, such as food assistance and housing vouchers, such as NAP, TANF, WIC, and Medicaid are meant to fill in the gaps. Those gaps, however, are just as often yawning chasms that seem impossible to close. The so-called safety net has all but disappeared.

Is the American Dream Attainable for All?

There’s no simple answer to the question, but it’s probably a fair bet that those living in extreme – and even moderate – poverty face extraordinary challenges. In various places around the world, civil and religious wars, along with dire climactic changes prevent people from places like Syria and South Sudan from finding shelter or enough to eat. Inevitably, they migrate to safer places. In the U.S., individuals and families face the catastrophe of drug addiction, which devastates communities. Moreover, income inequality in the U.S. outstrips most other Western countries.

Then there is the stigma attached to poverty, at least in the United States. The American Dream is one in which individuals, by dint of industriousness, hard work, and frugality, pull themselves up by their bootstraps – a version of causa sui, or self-generation. Consequently, some thinking goes, poverty is the result of shiftless shirkers.

As it happens, things aren’t so simple. Here are two ways to begin thinking about the complicated life of a poor person. First, it’s not clear how a child is supposed to bootstrap themselves into the American Dream, or even be in a position to prepare for such a magical feat. Yet, as we’ve seen, children make up a large chunk of those living in poverty.

(Credit: Shovon Mondal, via Wikimedia Commons)

(Credit: Shovon Mondal, via Wikimedia Commons)

Second, and more generally, most of us don’t realize how difficult daily life is when you’re poor. Consider this analogy: Suppose you’re out running errands and realize you need a bathroom. You are too far from home to use your own toilet, so you pop into a restaurant, buy a cup of coffee or something so you can use the bathroom. Or maybe a gas station has a bathroom for patrons. You probably don’t consider the fact that a poor person (or a homeless person) can’t buy their way into a bathroom – and that’s for a basic bodily function. So, the poor person has to think ahead, plan, just for that.

Now expand your thinking to how much planning is involved in an entire day. I might quickly scan my grocery coupons for the best deals, for example, but I don’t have to look for the cheapest option for every purchase. Over the course of the day, according to research by behavioral economists and other specialists, a poor person has to make many more decisions than you and I. The poor person’s “cognitive load” is much heavier, and much more exhausting. That, in turn, can lead to poor decisions that make life even worse.

Last, but very much not least of the factors that make up a poor person’s life, is the instability of work. According to one sociologist’s decades-long research, poor people usually work in minimum- and sub-minimum wage jobs. Given that work shifts are adjusted daily to accommodate the ebb and flow of customers, workers often can’t secure a reliable, 40-hour-a-week schedule. Consequently, they are effectively beholden to work schedules that prevent them from focusing on other important aspects of their lives. In the United States, making a living and moving into the vibrant middle class – the essence of the American Dream – feels further and further out of reach for many.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. Among her relevant publications are essays in Mr. Robot and Philosophy: Beyond Good and Evil Corp (Open Court, 2017), Westworld and Philosophy: Mind Equals Blown (Open Court, 2018), Dave Chappelle and Philosophy: When Keeping it Wrong Gets Real (Open Court, 2021), and Indiana Jones and Philosophy: Why Did It Have to be Socrates? (Wiley-Blackwell, 2023).

Title image credit: Adobe Stock