The Civil War introduced a new kind of warfare combining warships and armies that made use of America’s varied topography and inventive minds.

◊

Since colonial times, America’s rivers were known as avenues of trade and transportation. One of the marvels of the New World for European settlers was how these wide and wild ribbons of water provided accessibility to the interior, encouraging exploration and settlement away from the coast. Their potential seemed unlimited – something the Native Americans who preceded them knew for centuries.

In Colonial America, rivers, even coastal rivers, did not play much of a role in warfare. A few scattered forts overlooked inland rivers during the French and Indian War, but there were no significant waterborne attacks. During the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, the enemies of the United States came by oceans, and even lakes, which could support the sail-powered warships of the time. That all changed with Robert Fulton’s development of steam power for ships.

When the Civil War began in 1861, U.S. military leaders had to change their strategic thinking, not only because of steam power but also because they were now faced with an internal enemy. Sturdy coastal forts, built to defend against an enemy from abroad, were quickly seized by the Confederate States of America. These forts were used against the Federals as the U.S. Navy attempted to create a coastal blockade which, together with seizing control of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, would isolate the South in the Anaconda Plan. The U.S. Army’s General-in-Chief, Winfield Scott, in his last major act before retirement, designed this strategy because he thought it would strangle the Confederacy into submission.

For more on the Civil War, check out the MagellanTV original series Battlefield America.

Grant Takes the Lead

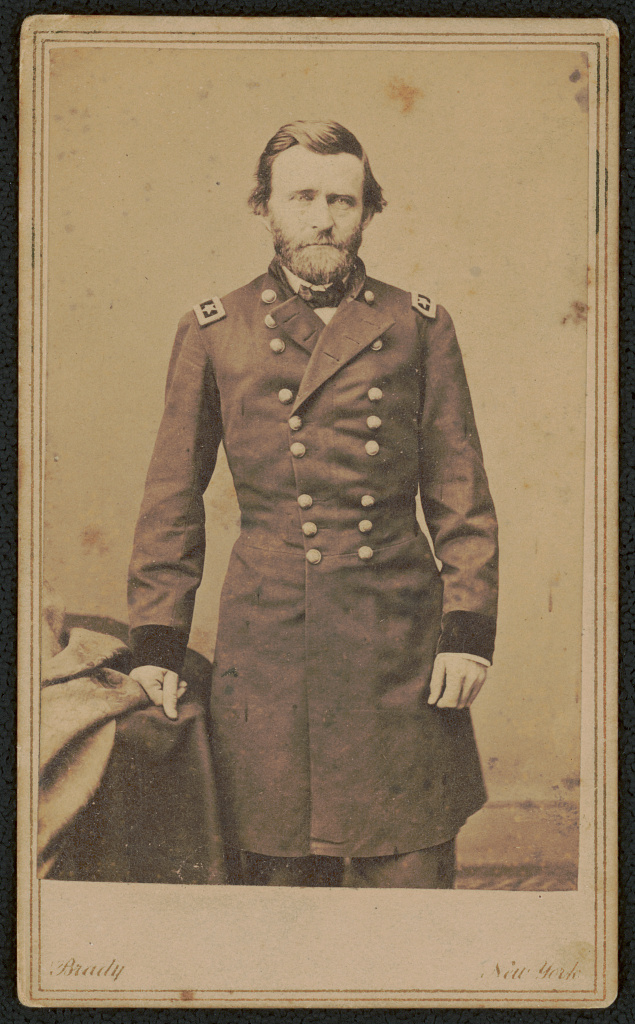

The South recognized its river vulnerability by racing to build fortifications on the vital waterways that split the Confederacy and exposed its interior to Northern incursions. One Federal commander, Ulysses S. Grant, quickly embraced the potential of the rivers. Born and raised along the Ohio River east of Cincinnati, and spending most of the 1850s in Galena, Illinois, and St. Louis, Grant knew the rivers and river transportation as well as anyone in the Army.

Though he served well in the Mexican War as a young West Point officer, Ulysses S. Grant fell into obscurity until he was appointed as a colonel of volunteers in 1861 by the governor of Illinois.

From his new headquarters at Cairo, Illinois, Grant launched an operation to Paducah, Kentucky, where the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers flowed into the Ohio. Kentucky’s proclamation of neutrality had already been violated when the Confederates seized Columbus, on the Mississippi. Columbus and Paducah were important ports with strategic significance in the war’s first year.

Grant disliked the other steam invention of the early 19th century, trains, as a means of military transportation and supply. The rapidly expanding railroads of the North and the sporadically built rail lines of the South were subject to equipment breakdowns, civilian control, differences in track gauge, sabotage, and cavalry raids. By contrast, river steamers could move Army units and military supplies quickly while other riverboats, sporting a few pieces of naval artillery, protected them. At the same time, enterprising contractors were showing the U.S. Navy designs for ironclad river gunboats.

Ulysses S. Grant (Credit: Photograph by Matthew B. Brady, via Library of Congress)

Grant got his first taste of river war action in November of 1861. In order to block a Rebel unit headed to join the Columbus Confederate garrison, Grant attacked its camp on the opposite bank of the Mississippi at Belmont, Missouri. Initially successful, the Federals were cut off by Southern reinforcements from Columbus. Grant organized an escape under the protection of the wooden gunboats that accompanied the soldiers. Unperturbed by the setback, Grant learned from the experience. He also teamed with a combat-minded Navy commander, Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote.

Sixty miles south of Paducah, two forts protected the water entrances to General Albert Sidney Johnston’s vast Confederate defense line, which stretched from the Mississippi to the Cumberland Gap in the Alleghenies. Fort Henry on the Tennessee River was a hastily built earthen fort on low ground. Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River was a little better sited.

In the first major Federal offensive of 1862, Grant left Paducah on February 4 with 15,000 soldiers on Foote’s transports, accompanied by three ironclad and four wooden gunboats. Foote’s gunboats pounded Fort Henry on February 6. The fort surrendered after a two-hour artillery shelling, although the Confederate commander had earlier evacuated his infantry, sending them 10 miles east to Fort Donelson. Leaving a garrison, Grant marched the rest of his force to Fort Donelson while the riverboats sailed back down the river until they could cross to the Cumberland River.

Locations of major battles in the Western theater of the Civil War (Map by Hal Jesperson, CWMaps.com, via Wikipedia)

With the arrival of reinforcements and the gunboats, the siege of Fort Donelson commenced. But the shelling of the Federal ironclads didn’t pound the fort into submission. Amid muddy conditions and snow, Grant’s force fought off a breakout attempt by some of the Rebel infantry. Were it not for division in the fort’s Confederate leadership, where only one of the three commanders was a professional soldier, the plan might have succeeded. But on February 15, Grant’s infantry began to gain ground on the fort. That night, the two political generals and the cavalry, under Nathan Bedford Forrest, escaped, leaving Grant’s West Point friend, Brigadier General Simon Bucker, to surrender the fort according to Grant’s unconditional surrender terms.

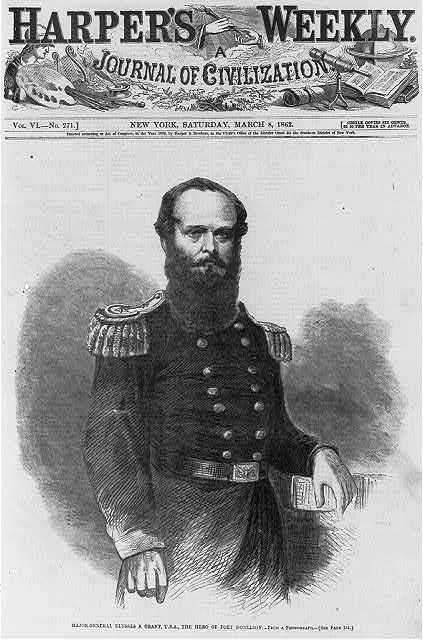

Grant’s Star Ascends

Grant gained national recognition with the Fort Donelson victory and his “unconditional surrender” mindset. He was immediately promoted to the rank of major general. The victory also enabled the North to pressure Nashville. The Tennessee capital gave up without a fight. Another result of Grant’s victory was the Rebel abandonment of Columbus, with the Confederates establishing a new fort on the Mississippi further south.

Grant on the cover of Harper's Weekly, 1862 (Source: Library of Congress)

Grant next aimed his Tennessee invasion toward one of the South’s key rail junctions at Corinth, Mississippi. He selected the best all-weather docking location north of Corinth, Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. There he waited for the Army of the Ohio under Don Carlos Buell to join him. The overwhelming force would then penetrate the heart of the South.

It didn’t work out quite like that. General Johnston assembled a large force at Corinth, meaning to attack Grant’s army before Buell’s arrival. On April 6, the Rebels launched a surprise attack on the Federal camps west of Pittsburg Landing, in a battle called Shiloh by the South. They were initially successful until some determined resistance by Grant’s subordinates, who held out until Grant was able to create a new line backed by artillery. Johnston was killed that Sunday and the next day, with gunboat help and the arrival of Buell’s men, the Federals turned the tide of the battle.

Without Johnston’s leadership – or perhaps even with it – the Confederates could not hold the field. They withdrew toward Corinth on the night of April 7.

Dividing the Western Confederacy

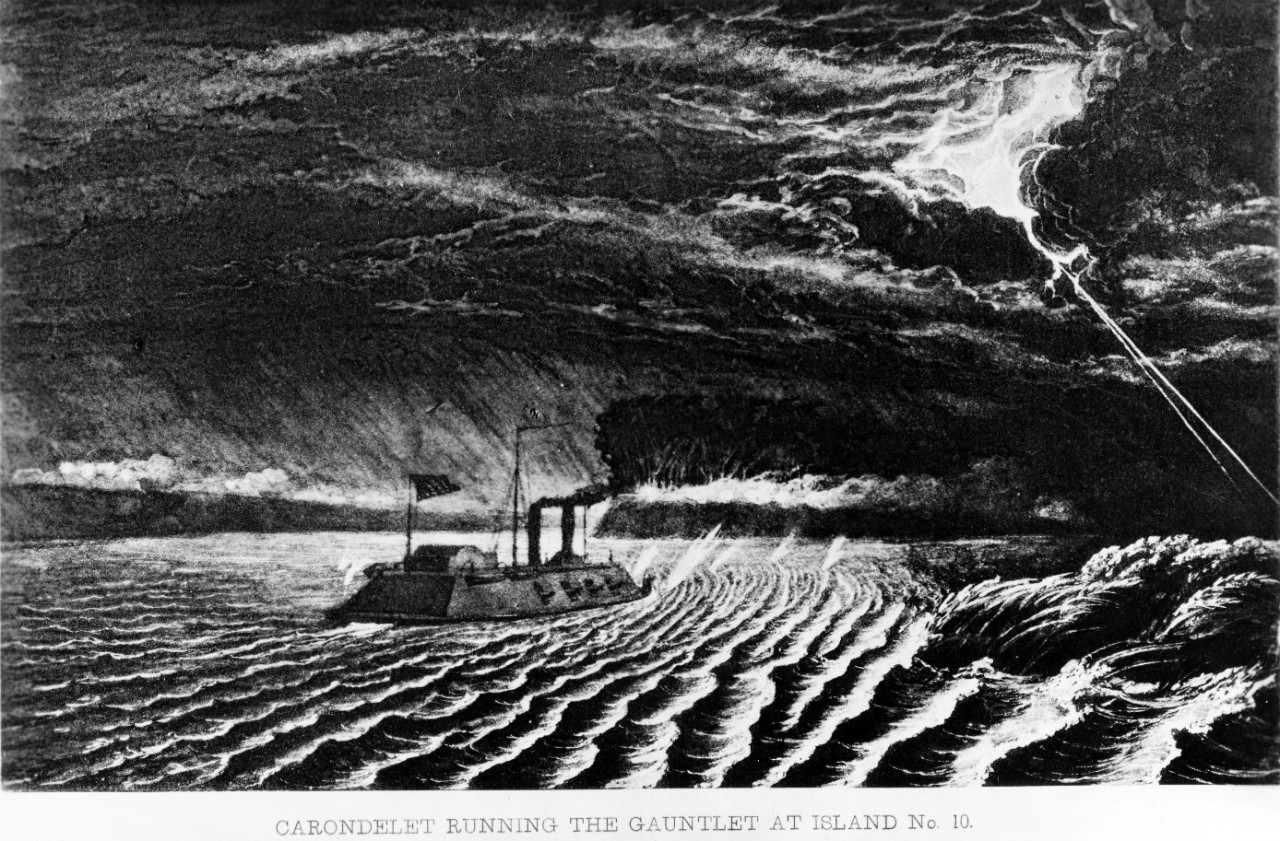

There was also trouble on the western end of the line Johnston had created. Another rising Federal general, John Pope, was moving south on the Mississippi River in the vicinity of New Madrid, Missouri. But without Navy help, Pope could not get his army into position to attack the strong fort at Island No. 10, which the Confederates established after Columbus fell.

A spectacular nighttime naval bombardment of the Rebel fort began on March 16 and included huge 13-inch mortars mounted in river barges lobbing explosives into the earthworks, but the garrison held out. On April 4, two of Foote’s ironclads ran by the fort and were able to protect Pope’s force as they crossed the Mississippi. The Federals then commanded a position to force surrender of the fort. The Rebels had to retreat down the Mississippi once again.

USS Carondelet on the Mississippi River, April 4, 1862 (Source: Naval History and Heritage Command)

By May 6, after a short naval engagement involving rams (fast steamers with large rams tied to their prows), Memphis also fell into Federal hands. Tennessee was seemingly being ripped to shreds by Yankee incursions. Well, almost. Beyond the rivers, there was plenty of fight left in the Rebels, including a strong cavalry force trained to fight like infantry by its notorious leader, Nathan Bedford Forrest.

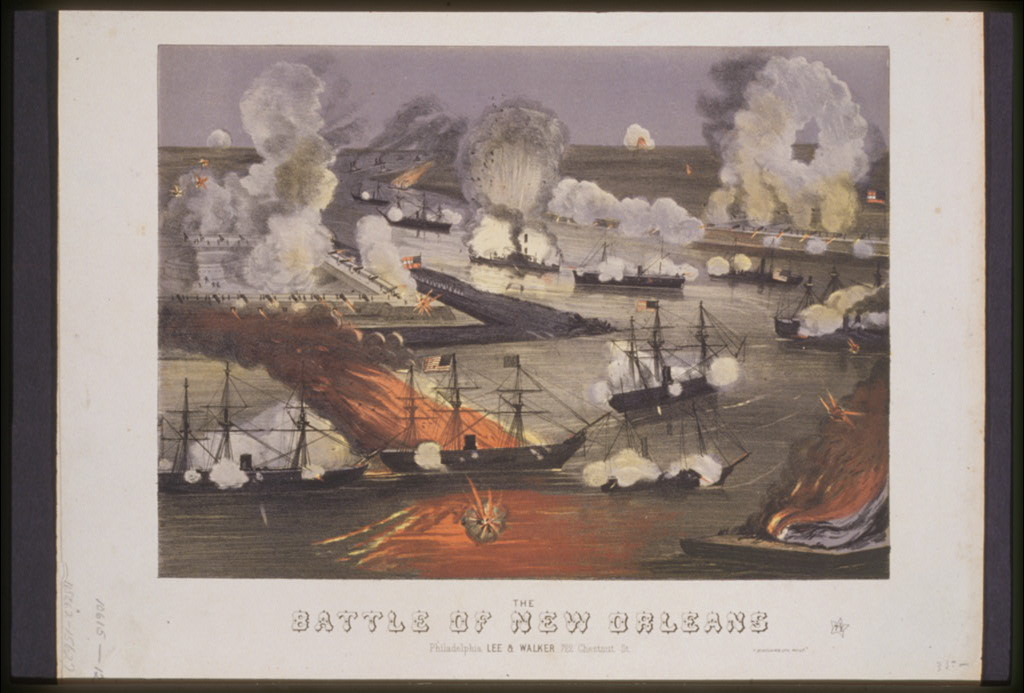

Where the Mississippi flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, Flag Officer David G. Farragut, a venerable U. S. Navy officer, prepared to conquer the Mississippi River from the other end. His strategy was to run his ocean-going fleet up the Mississippi past two Rebel forts 50 miles south of the largest Confederate city, New Orleans. One of them, Fort Jackson, was a former U.S. Army brick fortress seized by the Rebels.

On April 24, 1862, a night of spectacular shelling resulted in the fort being successfully bypassed. Farragut took his ships north to the essentially defenseless city of New Orleans. The Crescent City surrendered. The South lost its second capital of the year when Baton Rouge also came under Farragut’s threatening sail-and-steam navy and was successfully occupied later. But, frustrated with not being able to take the strong Confederate fortress at Vicksburg, Mississippi, Farragut’s squadron returned to the sea.

(Source: Library of Congress)

Despite Federal control of Memphis and New Orleans, the Mississippi was still open for the Confederates to bring much needed supplies and manpower from the Trans-Mississippi (western Confederate states of Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas) by way of the Arkansas and Red rivers. The imposing guns at Vicksburg and Grand Gulf, Mississippi, and a new fort at Port Hudson, Louisiana, still denied the Mississippi River to the North.

The Father of Waters Again Goes ‘Unvexed to the Sea’

Vicksburg was a campaign that showed a persevering U.S. Grant opposing an equally determined foe that did not give up the fight. Once the calendar turned from 1862 to 1863, Grant put a disastrous December campaign called Chickasaw Bayou behind him, an attempt to get through the “backdoor” of Vicksburg’s strong defenses via swamps north of the city. He turned his attention to bypassing Vicksburg through a series of routes from Federal-held northeast Louisiana.

All these attempts ended in failure. He called again on the Navy, now under the command of Rear Admiral David D. Porter, who had led the mortar boats in Farragut’s New Orleans operation. On April 16, 1863, Porter repeated the successful tactic used by Farragut and Foote: His gunboats ran the gauntlet of Vicksburg’s massive artillery defense and established a Mississippi River position south of the city.

Transports were run past the guns as well, allowing Grant to ferry his forces across the river at Port Gibson in early May. From there, his men marched on a long route east to Jackson, the Mississippi capital. They captured it then headed west to Vicksburg. The Federals surrounded the city with entrenched troops while gunboats guarded against any communication with the river.

Under siege from all sides, the Vicksburg garrison held out for nearly seven weeks, but surrendered on July 4, 1863. With the fall of Port Hudson a few days later the Mississippi flowed, as Lincoln stated, “unvexed to the sea.”

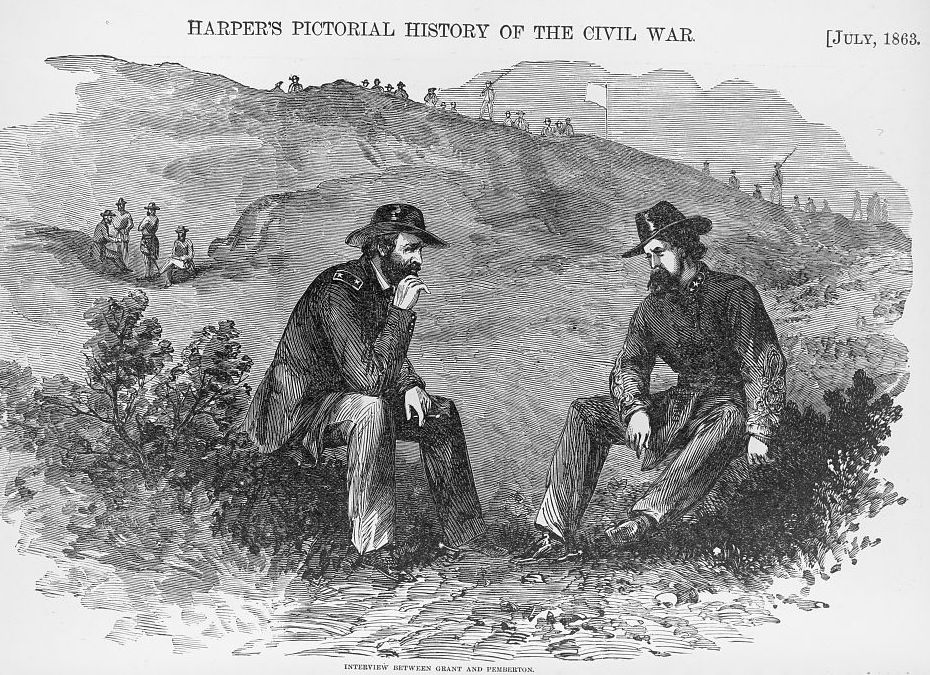

Maj. Gen. Grant and Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton meeting during Vicksburg surrender negotiations, 1863. (Source: Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War, via Library of Congress)

Differences East and West

In late 1863, Grant would be back on the Tennessee River, assuming control of the army of a disgraced general, William S. Rosecrans. The Union Army of the Cumberland was virtually surrounded in Chattanooga, Tennessee, after it was driven from northwest Georgia in the Battle of Chickamauga. Grant took charge and broke the stalemate by opening a line of supplies via the Tennessee. Before too long, a spirited group of Federal officers – Rosecrans’s corps generals and Grant’s most trusted subordinate, William T. Sherman – led their men into action, driving the Rebels from Chattanooga and paving the way for Sherman’s march through Georgia the following spring.

The last Federal attempt to carve up the South through river incursions and effectively terminate Rebel resistance in the Trans-Mississippi did not end well. A strong-willed Union general with great political connections, Nathaniel Banks, was creating havoc with ambitious but flawed plans. Though his command had captured Port Hudson, his May 1864 campaign to take Shreveport, Louisiana, met with failure when Banks’s troops were turned back by stiff Rebel resistance at Mansfield. Porter’s ironclads that accompanied the soldiers narrowly escaped destruction thanks to the cleverness of a Federal engineering officer.

For in-depth accounts of six critical Civil War battles, watch the MagellanTV original series Battlefield America: The Civil War.

Rivers, so vital to Federal victories in the West, proved to be the strong allies of Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia in the East. When the Federal spring campaign was launched in May of 1864, Grant, in command of all Federal forces, traveled with the Army of the Potomac through central Virginia, while Sherman prepared to knife through Georgia.

Gettysburg victor Major General George Meade had done little to weaken the Army of Northern Virginia after that tide-shifting battle. Grant meant to change that. But in Virginia, Grant would find a different kind of River War, one in which rivers became obstacles, not aids, to Union armies. Rivers with names such as the Rapidan, North Anna, and Chickahominy became barriers to the Union advances in this difficult and bloody offensive.

The world had not seen river warfare and the special watercraft used to fight it before the American Civil War. Nor would this type of warfare be used on any significant scale for the next 100 years until it reemerged in the Vietnam War.

Ω

Jay Wertz is an award-winning author, publisher, and filmmaker. He has written seven books, including four volumes in the War Stories: World War II Firsthand™ series. Other books include The Native American Experience; The Civil War Experience 1861–1865; and Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, co-authored with Edwin C. Bearss. He is the editor and a primary contributor to D-Day 75th Anniversary – A Millennials Guide and other works for Monroe Publications. He has been a columnist and online contributor for Civil War Times Illustrated, America’s Civil War, Aviation History, Armchair General, and America in WWII magazines. He is also the producer-director-writer of the documentary series Smithsonian’s Great Battles of the Civil War for The Learning Channel and Time-Life Video.

Title Image: Federal smoothbore artillery on the Vicksburg Line near the Illinois Monument (Source: Library of Congress)