Diana Vreeland introduced an independent verve to American fashion, first from her position as fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar magazine and then as editor-in-chief at Vogue. She brought sporty styling to dresses and moved the ideal of female beauty from poised society women draped in gowns to athletic models in colorful and revealing outfits. Vreeland’s work granted women freedom to create their own styles. Over 30 years after her death, she is revered as fashion’s preeminent oracle.

◊

In 1960, Senator John F. Kennedy had a problem unique in the history of American politics. His young wife Jackie was seen as too glamorous – too European in style for the wife of a Democrat running for president.

This was not just a problem of perception, as Mrs. Kennedy’s wardrobe would be inevitably compared to the plain style of GOP candidate Richard Nixon’s wife Pat. Reports of Jackie spending thousands of dollars on outfits made in France from the famed couture houses of Chanel and Balenciaga bothered the leaders of two giant U.S. garment worker unions. Those groups had already donated over a quarter million dollars to Kennedy’s campaign, and they wanted something done about his wife’s un-American wardrobe.

Jackie knew exactly whom to call for help – the fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar magazine, Diana Vreeland. They had known each other for years, but then Vreeland, the daughter of high society British/American parents, knew everybody.

Sent to Wyoming with her sister in 1916 to escape a polio epidemic in New York, Vreeland was taught how to horseback ride by her mother’s friend, Buffalo Bill Cody.

Bazaar’s fashion editor for a quarter-century, Vreeland was a high-flying eccentric genius whose vivid imagination for clothes, interior design, photographs, and, above all, dynamic personalities – hers foremost – redefined how two generations of American women saw themselves.

She styled Mrs. Kennedy in outfits from three American sportswear designers, then helped plan a white gown for the inaugural ball that was sewn at Bergdorf Goodman, New York’s elite shop for women. Vreeland also found Jackie’s iconic pillbox hat, created by a then unknown young milliner, Roy Halston, whose fortune was made on the spot. Vreeland’s style advice to the young first lady reflected a fashion world undergoing a rapid transformation.

Changing Clothes With the Times

In the 20th century, women’s fashion reflected a new and dynamic female image. Long dresses, big hats, high-button shoes, and corsets fell away in favor of shorter skirts, pants, and sandals. These changes began in Paris and created a mass market for clothing to accommodate new social roles for women. By mid-century, American fashion companies led the way with sporty and revealing outfits that merged elegance with ease.

For most of the century, rules defining hemlines, silhouettes, colors, and fabric suitable for well-dressed middle- and upper-class American women were dictated by two periodical fashion guides: Harper’s Bazaar, where Vreeland reigned as fashion editor from 1939 to 1961, and Vogue, where she moved in 1962, becoming its editor-in-chief a year later. She was perfect for the roles, having become an expert on stylish fantasy and self-invention at an early age.

Born Diana Dalziel (a Scottish family name pronounced Dee-El) in Paris in 1903, she was raised in an upper-class New York milieu. For all her privilege, Vreeland’s childhood had been unhappy. The product of a failed marriage, and with a big nose and wide mouth, Diana was rejected by her frivolous mother, who obviously preferred her beautiful younger sister, Alexandra. Diana did badly in school before quitting formal education in her early teens to study dance with a Russian ballet master. The experience gave her a towering sense of discipline, a love of performance, and a sinuous poise.

In the ‘20s, newspaper society columns reported on her vivid personal style, her social set that frequented Harlem jazz clubs, and her marriage, at 21, to one of the city’s handsomest men, Reed Vreeland, a Yale-educated international banker.

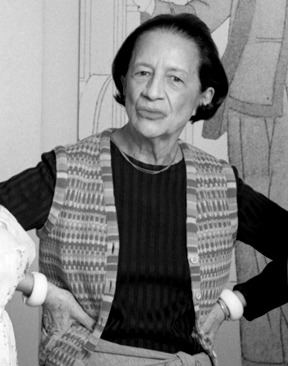

Diana Vreeland in 1978 (Credit: Lynn Gilbe, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

A life of high-styled leisure, at their home in London, was hers for a time. She ordered outfits from Paris couturiers, notably Coco Chanel, whose trim outfits were then revolutionizing women’s fashion. But in 1935, Reed was ordered back to New York, his banking career essentially over.

In 1936, She caught the eye of Bazaar’s editor, Carmel Snow, a legendary judge of talent, who reportedly noted Diana’s outfit as she and Reed were dancing at a party. Now with two young sons, Diana accepted the Bazaar position, her first salaried job, because her family needed the money.

Vreeland Goes to Work

Vreeland was an immediate sensation with her style ideas for the magazine, first articulated in a regular feature called “Why Don’t You…” that offered fashion suggestions ranging from the practical to the surreal: “Why don’t you have the sleeves of your mink made square and bulky and cut off six inches above the wrist?” or “… embroider enormous red lobsters on a pure heavy white silk tablecloth and mark it with a bright blue monogram?” Then there was the notorious “Why don’t you rinse your blonde child’s hair in dead champagne to keep its gold, as they do in France?”

Vreeland used droll fantasy to invoke romantic possibilities in everyday life. This sense of using unique style to define a woman’s identity was something very new for a fashion trade that relied on paternalist traditions that mainly kept women in conforming social roles while promising to make them attractive. Vreeland, who was named Bazaar’s fashion editor in 1939, promoted her daring message of independent feminine confidence and unconventional beauty for the rest of her professional life. In time it became the central outlook of women’s fashion.

Vreeland’s groundbreaking style was an excellent fit at Bazaar. Its innovative art director, Alexey Brodovitch, was redefining magazine design with a cinematic approach to sequencing pages using big pictures, varied blocks of text, and ample white space to move the reader through each issue.

Vreeland shows a visitor around an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976. (Source: National Archives and Records Administration, via Wikimedia Commons)

This thoroughly modern approach was enhanced by surrealist artists like Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, and Salvador Dali. Bazaar photographers included Cecil Beaton, Martin Munkacsi, and Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Vreeland and Dahl-Woolfe would spend weeks planning and styling location shoots that glorified long-limbed, athletic female bodies. These assignments, one featuring a Vreeland discovery, 16-year-old Lauren Bacall, are masterpieces of fashion photography.

As described by her principal biographer, Amanda MacKenzie Stuart, Diana was assigned to cover the American fashion business headquartered in New York’s Garment District. Though creatively minor compared to European firms, they accounted for much of Bazaar’s advertising. Vreeland’s photo shoots modified American clothes to more stylish effect; her changes and recommendations were then incorporated by manufacturers.

American Fashion, Born in a Time of War

War broke out in Europe in September 1939, severing the connection between the New York and Paris style worlds. For the next seven years, Vreeland was instrumental in guiding the true birth of American fashion. Following her lead, U.S. sportswear designers began mass producing functional, attractive, clean-lined outfits, inexpensive and easy to care for, which Vreeland featured in Bazaar.

The trend peaked in 1942 with the so-called popover dress. A pullover shift of cotton or another simple fabric, with a cinched waist, the popover was conceived by Vreeland and detailed for manufacture by the pioneering woman designer Claire McCardell. It was an immediate hit with women who were joining the workforce in unprecedented numbers – and it remains today, in infinite variations, an essential garment.

After the end of World War II, Paris fashion began its climb back, led by the revival of highly tailored couture from Christian Dior, a new player enthusiastically promoted in the pages of Bazaar, and the reappearance of Coco Chanel and the house of Balenciaga.

As fashion’s focus returned to Paris, Vreeland remained stuck at Bazaar’s New York headquarters, an assignment that increasingly chafed until she was lured to the staff of American Vogue in 1962. Now a celebrity in her own right, she embarked on an extravagant fashion project as editor-in-chief, with photographers such as David Bailey, Bert Stern, Irving Penn, and, also plucked from Bazaar, Richard Avedon.

“Blue jeans are the only things that have kept fashion alive,” Vreeland insisted. “They’re the most beautiful things since the gondola.”

Appearing twice monthly, Vogue kicked Vreeland’s imagination into high gear. Using huge budgets for location shoots in exotic locales, she gave her creative teams often mysterious instructions regarding what she wanted for the magazine’s lavish photo spreads. Vogue looked dazzling, but the practical needs of her readers and advertisers began getting lost. Widowed in 1966, Vreeland became increasingly overbearing and demanding to work for. Dedicated to her vision of vivid, self-aware women, she missed the changing times.

Both Vogue and Bazaar were slow to understand the desires and interests of young women in a late-’60s anti-establishment atmosphere of liberation and greater professional ambition. Sales of the magazines tumbled, and, in 1971, Vreeland lost the editor-in-chief job.

The influence of Diana Vreeland is still felt in the high fashion of today. (Source: StockSnap from Pixabay)

From Fashion Dinosaur to Mythic Creature

Vreeland soon hired on as special consultant to the Costume Institute at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. There she staged lavish, wildly popular exhibitions, the first of their kind, of vintage clothes ranging from Europe’s Belle Epoque to Hollywood. More famous than ever, Vreeland partied with the likes of Andy Warhol, Jack Nicholson, and Mick Jagger. But the museum shows, however glamourous, were a look back. After a long illness, brought on by a lifetime of smoking, she died of a heart attack in 1989. By then a style dinosaur, Vreeland has since become a mythic creature, fashion’s great prophet.

“To be a SURF-er! . . . ah, to be between the sky and the water would be a wonderful thing,” an enraptured Diana told an ’80s television interviewer. “Also skateboards I think are great! Great!”

There are long-standing problems with the fashion trade – wasting resources, relying on slavish conditions for garment workers, prioritizing values of the very rich, and a vision of female beauty that went from Vreeland’s athletic ideal to a body image unforgivingly thin. With #MeToo-era revelations of predatory behavior toward models of both sexes by photographers and fashion executives, along with the collapse of retail stores and the magazine business, Vreeland’s world can seem irrelevant at best; at worst, a prelude to the current collapse.

But Vreeland remains important for what she articulated in her magazines and promoted in American fashion. Her two volumes of memoirs, Allure, and D.V., are filled with arch observations, and some tall tales, drawn from a very creative life. Her aesthetic philosophy was all about the inventive possibilities that people must find to flourish in a hard world.

A story from the end of her life says it best. Having trouble breathing, and kept waiting in a New York City emergency room, the 85-year-old Diana became entranced with the sight of the shooting and stabbing victims admitted ahead of her, the floor splashed with their blood. “Oh! it’s like the back streets of Naples!” she exclaimed to her grandson. “ANYthing could happen!”

Ω

Title Image: Cloth Wave Movement in the Air on Blue Sky Tone Background by user bluehand, via Adobe Stock.