Clint Eastwood became a big star in a low-budget western that gave a new sense of drama to a tired genre. But his last “cowboy movie” exposed the truth behind the mythic depictions of the Old West.

◊

In 1964, a B-list TV actor known for amiable, rough edged, cowpoke roles flew economy class to Italy. He was being paid $15,000 (approximately $135,000 today) to star in a western to be shot at Rome’s Cinecitta film studio, and on location in Spain. The low-budget film wasn’t released in the U.S. until early 1967. It caused a sensation.

The actor was Clint Eastwood and the movie A Fistful of Dollars. By the time director Sergio Leone’s third installment of his “spaghetti western” trilogy, The Good the Bad and the Ugly, was released in the U.S. in late ’67, Eastwood was an international star, and westerns, a durable movie genre, would never be the same. For the next two decades, “cowboy movies” became vehicles of revisionist history that took new, sometimes harsh looks at an American past that the genre had previously glorified.

And no actor embodied the new western more fully than Eastwood. He starred in and directed a handful of films featuring a single, drifting horseman who appears in the lives of small communities in need of help. His aid always involves a violent settling of scores via gunplay in which Good wins over Evil before the horseman rides off alone.

Check out Secret Life of Clint Eastwood on MagellanTV.

But Eastwood’s last western, 1992’s Unforgiven, which he produced, directed, and starred in, thoroughly debunks the myth of the gunfighter, revealing it as a literal pulp fiction invention. More than that, he shows how the strong and silent killers he played in so many films were fundamentally pathetic, broken human beings.

The Mythic Drama of the West

The American West, with its harsh extremes and dramatic scenery, has long been a narrative setting for the European imagination. For Indigenous nations, the North American continent was a dynamic landscape of networked hunting and trading territories, peopled with enemies and allies, that offered deeply spiritual experiences grounded in the dangers and hardships of the natural world. White pioneers, with no access to a rich, existing cultural framework, saw it mainly as awesome real estate ripe for conquest and exploitation.

For the great majority of settlers, the West was a world of potential riches, not a spiritual realm, and the drama the public imagined for it repeated heroic themes dating to at least the Middle Ages: noble knights setting out on horseback across vast and hazardous distances on sacred quests or crusades against pagans and infidels.

These old storytelling tropes of Good versus Evil projected perfectly onto the American West. Beginning in the mid-19th century, dime novel adventures and live entertainments – the so-called Wild West shows of Buffalo Bill Cody and others – retold this basic story. Knights turned into cowboys and horse soldiers, while native people were a grim substitute for infidels.

A poster for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Credit: Library of Congress)

The First Movie Westerns

With the late 19th century advent of moving pictures, the earliest westerns were films of Wild West show routines such as the robbing of stagecoaches or the supposed heroism of Custer’s Last Stand. The first scripted western dramas, like 1903’s The Great Train Robbery, were shot in New Jersey.

Once the movie business moved to Hollywood, westerns became a reliable staple, mostly because they were cheap to make. Authentic locations were just a short hop out of town, and their casts mainly consisted of real cowboys from California ranches and former Wild West show performers, like Tom Mix. The movies had plenty of romance, cartoonish violence, and reliably happy endings. They would be a central pillar of worldwide popular entertainment for decades to come.

But by the mid-1950s, the genre became stale as westerns made a transition to the small screen. Immensely popular TV shows like Bonanza, Wagon Train, Maverick, Gunsmoke, and Rawhide entertained millions every week with their simple plots, likable characters, and idealized notions of what life in the Old West was like.

Eastwood had a starring role on TV’s Rawhide for five years before he got the call to go to Italy.

Meanwhile, western movies had taken firm root in Italy ever since the country’s occupation by the U.S. Army during and just after World War II. On the one hand, how did those rough Americani appear to Italians but as real life cowboys? On the other, American movies ran in Italian cinemas for years before the country’s film industry revived itself in the early 1950s. Keep in mind too that Italy itself was a setting for many of the chivalrous tales of knighthood told since the Crusades.

In fact, A Fistful of Dollars, set in Mexico, imported a dramatic Latin element to the western. Most of the American West, after all, had once been part of the Spanish Empire, just as the entire cowboy tradition came directly from the ancient system of cattle ranching endemic to Mexico. Leone’s great insight was to give a truly operatic feel to the “horse opera,” injecting new levels of passion (helped by an all-time great musical score by composer Ennio Morricone) to what had become a tired genre.

The Spanish word vaquero, meaning a herdsman, became the American synonym for cowboy: buckaroo.

A Reimagined Western Comes Out of . . . Japan??

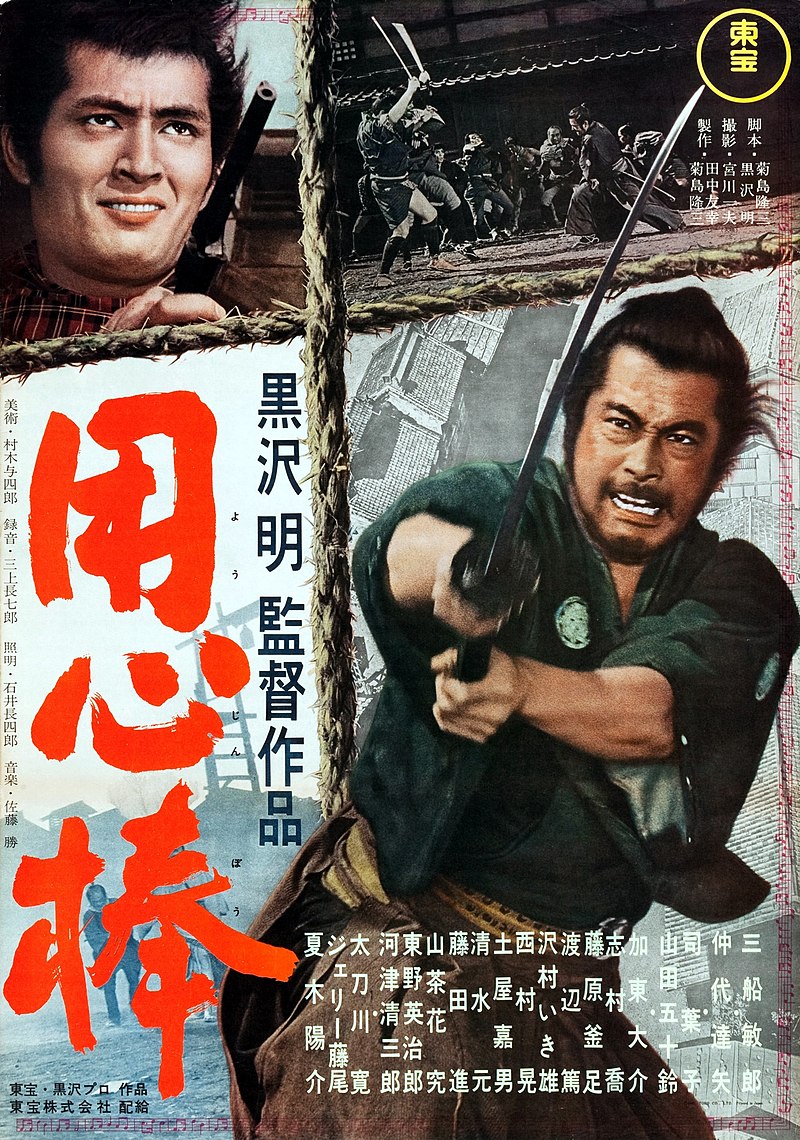

When Leone explained the plot of his project, Eastwood, an avid moviegoer, realized it was a remake of the 1961 Japanese classic, Yojimbo, directed by Akira Kurosawa. In it, a nameless samurai, played by Toshiro Mfume, arrives in a village ruled by criminals and proceeds to set two rival clans against each other by working first for one and then the other. It ends with a climactic battle in which the samurai slays the remaining bad guys before moving on.

Poster for Akira Kurosawa’s epic Yojimbo (Source: Wikipedia)

In forming Eastwood’s film character, The Man with No Name, Leone “borrowed” several features of Mfume’s role. The poncho Eastwood wears throughout has the same silhouette as Mfume’s samurai robe, while Eastwood keeps a cheroot clamped in his jaw just as Mfume’s character chewed on a small stick.

A little over halfway through A Fistful of Dollars, Eastwood’s character suffers a savage beating at the hands of the bad guys, and then extracts much of his revenge without at first resorting to gunplay. But there is, of course, a showdown shoot-’em-up on the town’s main street at the end. Attentive moviegoers will note how this scene is choreographed very much like the sword-swinging showdown that ends Yojimbo.

Kurosawa based Yojimbo on what can be called a modern western novel: Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett. In it, a nameless private detective arrives in a thinly-disguised Butte, Montana, during a 1930s miners’ strike and proceeds to clean up the town by pitting one corrupt outfit against another.

A New, Honest Look at the Old West

In Unforgiven, 21 years later, Eastwood gives a nearly point-by-point deconstruction of the role he played in one form or another since the spaghetti westerns. His character now has a name: William Munny (pronounced money), certainly a nod to the title of Leone’s film.

An ex-gunfighter and reformed alcoholic, Munny is raising hogs on a hardscrabble prairie farm when a young killer, The Schofield Kid, comes with news: a group of small-town prostitutes is offering a bounty of $1,000 on the lives of two cowboys to avenge the face-slashing of one of their own. Munny reluctantly signs up, bringing along his old partner in crime, Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman).

The film presents from the start a grim social order of sad and unsavory characters: abused women, brutish men, heartless killers, and a sheriff, Little Bill Daggett, a former gunfighter played by Gene Hackman, who viciously keeps his idea of order in a remote Wyoming town.

Eastwood as the desperate hired killer, William Munny, in Unforgiven (Credit: Malpaso Productions/Warner Bros. 1992)

The first to answer the prostitutes’ offer, a hired assassin called English Bob (Richard Harris), is accompanied by a dime novel author whose current project is to glorify (which means lie about) the exploits of this brutal, albeit stylish, thug. After Daggett beats up Bob and sends him packing, the pulp writer transfers his loyalty to the sheriff, who is happy to describe to him just how squalid and chaotic gunfights really are.

Soon it is Munny’s turn to get a thorough beating from Daggett. The punishment is clearly modeled on the abuse given to The Man with No Name in Fistful. Eastwood even re-creates a sequence from the earlier film showing his character dragging himself across the floor to escape his tormentors. Once he recovers, he and his two associates bushwhack the offending cowboys, killing them in cold blood. However, a deep remorse sets in.

After Logan is captured and killed by Daggett, Munny, back on the bottle, heads into town to exact his revenge. In his own homage, Eastwood here has Little Bill repeat nearly verbatim a line voiced by Yojimbo’s chief bad guy, saying he’ll meet Munny in Hell.

Eastwood dedicated Unforgiven “to Sergio and Don,” the latter being Don Siegel, who directed Dirty Harry (1971), the first of five Eastwood films featuring the exploits of San Francisco Detective Harry Callahan.

In one of Unforgiven’s most arresting lines, Munny says he’s “always been lucky when it comes to killin’ folks” – a very meta appraisal of Eastwood’s film stardom, which also included modern day characters handy with firearms.

Unforgiven won Best Picture and Best Director Oscars for 1992, and is widely considered the greatest western ever made (an appraisal I can’t disagree with). Though many films made in the wake of A Fistful of Dollars remodeled the genre in light of the historical record, none of them conducted such a thorough debunking of the subject. And, certainly, no screen icon of Eastwood’s stature ever so critically re-evaluated the roles that made him famous.

In its most radical departure from the western genre, Unforgiven doesn’t give us any good guys. There are no heroes, only broken people acting out of weakness and anger in an isolated, if beautiful, setting. They live – and die – regretting the decisions they’ve made, or what hard circumstances have forced upon them. As such, it is more true-to-life than most films of any type ever get.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar in the New World. A resident of Livingston, Montana, he never gets tired of watching The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

Title Image: Clint Eastwood as The Man with No Name, in A Fistful of Dollars (Credit: Jolly Film S.R.L./United Artists)