The walls of England’s Westminster Abbey have seen 39 monarchs crowned, 16 royal weddings, and funeral processions with wakes unlike any others. Let’s take a look at the many symbolic objects and regalia to be included in next month’s coronation of King Charles III.

◊

In 1066, when William the Conqueror’s Norman army decimated the Anglo-Saxon troops of King Harold in the Battle of Hastings, England began a massive transformation in its culture, demographic makeup, religious institutions, and infrastructure. With the changes wrought by the newly crowned King William I came a few traditions that continue today. While his Christmas day coronation was not televised for the world to see, many of the symbolic images that defined that moment in history will be visible on the telly on 6 May 2023.

Draped in the Robe of the Estate, King Charles III will take his seat on the coronation chair with a jewel-encrusted scepter by his side. As the oldest person ever to ascend the throne and the longest-serving heir-apparent in British history, Charles Philip Arthur George will confirm his place on the timeline of British monarchs with the symbol-heavy pomp of his coronation celebration.

For more on King Charles III, check out the MagellanTV documentary Prince Charles: The Royal Restoration.

The Sovereign’s Orb and Other Hand-held Symbols

For as long as human beings have held positions of power over one another, we have used ceremonies and symbols to highlight the significance of that power. Whether a title is conferred based on lineage or founded upon an act of war – or even pulling a sword from a stone – official acknowledgement of a position of power comes about through anointments, portraits, and ceremonies. Even the phrase “to be crowned” conflates a rise to power with the symbolic headwear so often associated with it. Throughout coronation ceremonies in England, a few objects – including the Sovereign’s Orb, St. Edward’s Crown, and others – have been passed down throughout the centuries signifying that those who hold them are the sovereign leaders of what has been known as Great Britain since 1474.

The Ampulla and Coronation Spoon

Arguably the most important symbols of the ceremony take the form of a golden Ampulla and spoon. Continuing with a tradition that has been rooted in medicinal, spiritual, and symbolic events throughout the history of Christianity and Judaism, the King will be anointed with Chrism oil. For King Charles III’s coronation, the oil will have been consecrated in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem from a centuries-old recipe involving sesame, rose, jasmine, cinnamon, neroli, benzoin, amber, and orange blossom. The anointing will be conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who will sprinkle the oil onto the sovereign out of view of cameras, as this ceremonial activity is considered sacred.

While some objects used in the coronation will have ties to the Middle Ages, many were made after the English Civil War. Oliver Cromwell ordered that many of the Crown Jewels, including the original orb and scepters, be melted, broken, or sold to undermine the monarchy.

The oil is contained in the Ampulla, which is shaped like an eagle with its wings spread open, and the oil drips out of its beak. From the Ampulla, the oil is poured on the Coronation Spoon which is the oldest surviving object in Britain’s Crown Jewels. Made of silver and gilded with gold, the spoon dates back to the 12th century. When Oliver Cromwell began selling the Crown Jewels after the execution of King Charles I in 1649, an official from the wardrobe of Charles I bought the spoon and ensured its safekeeping until the monarchy was restored.

The Sovereign’s Orb

A symbol that predates the Norman Conquest, the Sovereign’s Orb (an example of a globus cruciger) was first used in investitures for Henry II, King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, in 1014. As such, the orb is a symbol that transcends the particularity of Britishness or even the monarchy. Henry II held the orb with a cross on its top as emblematic of his authority and reign over the Christian world. The globus cruciger to be used in King Charles III’s coronation was created in 1661 but reflects the design and symbolism of centuries before. In the form of a 2.7 pound golden ball with 9 emeralds, 18 rubies, 9 sapphires, 365 diamonds and 375 pearls, the Sovereign’s Orb puts the symbolic weight of the world in the king’s hands. Two lines of 375 pearls divide the orb into three distinct sections representing Europe, Africa, and Asia, the only continents that geographers in the Middle Ages knew to exist.

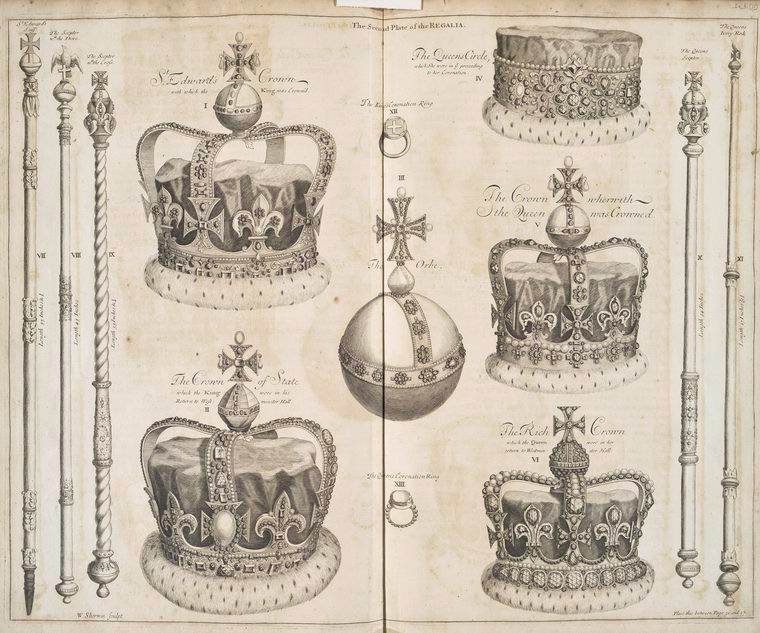

The crown jewels ahead of Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Historically, the object is designed to remind the incoming monarch that their power is conferred by God and that the Christian faith has dominion over the physical world. When placed in his right hand, the hollow sphere will indicate Charles III’s role as “Defender of the Faith” and “Supreme Governor of the Church of England.” King Charles is clearly eager to usher in a new, modernized monarchy that reflects the many religious and cultural practices and beliefs of the Commonwealth. In his many decades as heir apparent and preparing for the day when he would be king, Charles mentioned to media outlets that he would be a defender of faith, rather than just the Faith.

The Sovereign’s Scepter

Two scepters are integral parts of the ceremony: one having a cross on its top and the other with an enamel dove. The latter is known as the Rod of Equity and Mercy, and uses the symbol of the dove to indicate the monarch’s spiritual power in connection with the Holy Spirit.

The Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross, on the other hand, reinforces that the monarch’s reign is temporary and still under the dominion of God. It is a golden rod, 92 centimeters long, with a hilt enameled and mounted with rubies, emeralds, sapphires, and diamonds. The central part of the scepter spirals up in a golden twist toward the metaphorical and literal crown jewel of the piece – a heart-shaped structure supporting the Cullinan I diamond, which was presented as a gift to King Edward VII in 1907. Above the diamond is a smaller, traditional globus cruciger symbol, a faceted amethyst gem representing the world, supporting a cross of diamonds and emeralds. The Sovereign’s Sceptre will be placed in the king’s left hand on his way out of the ceremony.

At the time of its discovery, the Cullinan I was the largest polished diamond in the world at 530.2 carats.When incorporated into the scepter, jewelers had to reinforce the rod, as the diamond was so massive.

The Crown Jewels and Royal Wardrobe

St. Edward's Crown

When Charles is officially crowned, he will wear the iconic St. Edward’s Crown worn by his mother, uncle, grandfather, and every other king and queen who has preceded him since 1661. Weighing in at 4.9 pounds, the crown itself is rarely worn save for coronations. Its purple velvet cap and ermine band support a solid gold frame which criss-crosses to support rubies, amethysts, sapphires, garnet, topazes, and tourmalines. Framing the crown are four crosses-pattée and four fleurs-de-lis which draw the eye up towards the familiar sight of the globus cruciger at the top of the crown.

Coronation regalia, 1687 (Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections)

The Sovereign’s Ring and Other Accessories

One of the later additions to the coronation regalia is the Sovereign’s Ring. While placing a ruby ring on the monarch’s finger dates back to the 13th century, the ring used in British coronation ceremonies was designed for William IV’s investiture in 1831. Before then, each monarch had a custom ring made, but, starting with William’s daughter Victoria, the ring has since become a staple of the royal family’s inheritance. The ring itself is made up of gold, rubies, and sapphires. When the archbishop places it on King Charles’s fourth finger during the coronation ceremony, it will symbolize his dignity as sovereign. In addition to the ring, Charles will wear a pair of 19th-century golden spurs that feature a Tudor rose and velvet strap.

Portrait of Charles II of England in coronation robes circa 1661 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Robes

The ceremony itself follows a strict order of events and has traditionally been broken up into six parts: the recognition, the oath, the anointing, the investiture, the enthronement, and the homage. Throughout these several parts of the event, the sovereign will change into different robes. King Charles will wear the crimson Robes of State to enter Westminster Abbey and shortly thereafter don the plain Colobium Sindonis Robes to undergo the anointing in a humble state. During the investiture ceremony, Charles will wear the golden silk Supertunica before swapping it for the Robe Royal for the crowning, which symbolizes the divine status of being king. Exiting the abbey in full regalia, Charles will be wrapped in the Robe of Estate, its 6.5 meters and 15 pounds of purple velvet trailing him as he moves through the church and his first day as the formally crowned king of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Why is the Coronation Important?

The symbolic power of a traditional ceremony with over a thousand years of history cannot be boiled down to a few relics and fashion statements. The coronation ceremony marks a shift in the timeline of British sensibilities. A new leader ushers in a new era of values. And the celebration of this new king is an opportunity to redefine the symbolic power of the monarchy itself. The sound of the Gold Coronation Stagecoach clattering down the streets of London, flanked by cheering crowds waving the union jack might fill some onlookers with memories or feelings of patriotism that speak to more than just the glitz and glamor, power and privilege of the royal family.

The official emblem of the Coronation of His Majesty The King and Her Majesty The Queen Consort. Designed by Sir Jony Ive KBE (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

King Charles III, like his mother and his grandfather before her, will be head of state, though he will have little official power over the governmental affairs in the country. But, as the debate continues across the United Kingdom about the role and relevance of the monarchy in modern-day Britain and the commonwealth, the coronation serves as a reminder of the value of symbols within a society. Coronations symbolize change but also continuity, reinforcing tradition but with a new vision for the future.

Monarchs tend to be emblematic of the ethos of their reign. Be it King Charles II during the great fire of London in 1666 or Queen Elizabeth II in what she called the Annus Horribilis of 1992, sovereigns and the royal family give people a leader to look to in times of crisis. They also bear a hereditary celebrity that distracts average people from their own lives and enables them to fantasize about the luxurious lives of a fairy tale elite.

Thrones, capes, and spoons associate a new monarch with ideals of authority, dignity, and humility. The pomp and circumstance on 6 May 2023 will be an elaborate and expensive affair. With such a long and complex history, an ermine robe or enamel dove offers the world an opportunity to use objects as an entry-point for better understanding the symbolic power of British coronations – and of King Charles III himself.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. She also writes for Local Life magazine. Originally from Georgia, she went to college to study philosophy and studio art. She now works in Chicago as a local media specialist.

Title Image: The Tableau of the procession at the coronation of Queen Victoria on June 28, 1838, by Robert Tyas. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)