Is Michelangelo’s statue of David pornographic? It turns out the question isn’t new – it’s age-old and dates almost to its time of completion.

◊

The morning of September 13, 1501, felt full of promise for young Michelangelo Buonarroti. At 24 years old, he had already accomplished much, but now he had his biggest challenge to date, and he felt primed to go. With his tools at hand, he surveyed the colossal block of Carrara marble provided by the group that had commissioned a statue for the Florence Cathedral.

The block was not pristine. In fact, it had been exposed to the elements in the cathedral workspace for nearly 40 years, and it bore the cuts and indentations left by two other sculptors who had tried and failed to bring life to the cold, unforgiving marble.

But Michelangelo was not deterred. Just two years earlier, he had completed the Pietà in Rome, a career-making marble sculpture that announced to the world his prodigious skill. And, though apocryphal, perhaps he did utter this quote attributed to him: “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block before I start my work. . . . I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.”

We know from his wax models that he envisioned the final shape of this work before he first picked up his hammer and chisel. And so, that morning, he began chipping away at the marble slab that would eventually become the 17-foot masterpiece called David. It’s safe to say that at this moment he could not have foreseen either the lavish praise or the bitter condemnation his depiction of the biblical figure David would receive through the centuries to come.

Michelangelo was far from alone in depicting nudity in sculpted and painted images. For a comprehensive history of this facet of art history, view The Nude in Art on MagellanTV.

The Marble David: A History

Michelangelo labored over this massive statue for the greater part of three years. As he worked on it, the intention of the cathedral’s Overseers of the Office of Works, which commissioned the sculpture, was that David be hoisted more than 250 feet above the ground. It was to join a series of other sculptural works, including one by early Renaissance artist Donatello, atop the building’s buttresses.

For that reason, Michelangelo adjusted the perspective of the statue to emphasize its head and shoulders, making them bigger in proportion to the lower body, just as Classical Greek artists had done with figures meant to be seen from below. But to be suspended atop a column in the air was not David’s destiny.

In 1504, the year Michelangelo completed his work on the statue, city fathers took a look at the results and realized what a singular masterpiece they had on their hands. Engineers also realized what a herculean effort it would take to raise the six-ton hunk of marble up 250 feet to balance on a buttress.

So a committee of 40 elite citizens of Florence was convened to debate and decide on a new site for the monumental work. Distinguished panelists on the committee included fellow artists Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli. Nine sites were considered, and, in the end, the statue was hauled to the city square, in front of Florence’s government center, the Palazzo della Signoria, where it became an emblem of the city-state.

In the Palazzo, David’s face gazes southward, toward the rival city-state of Rome, as a powerful symbol of Florence’s determination to resist and repel any tyrants.

Despite the radical change in location, reception to the new sculpture was passionate. There was nothing to compare with it in its time. Educated admirers knew there hadn’t been a colossal heroic nude created in the known world since the antiquity of pre-Christian Greece and Rome.

The contemporary writer Giorgio Vasari, whose 1550 publication Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects is credited as being the first work of art-historical criticism, gushed over David: “It certainly bears the palm [i.e., is unsurpassed] among all modern and ancient works, whether Greek or Roman . . . and the colossal statues of Montecavallo [i.e., of Roman antiquity] do not compare with it in proportion and beauty.”

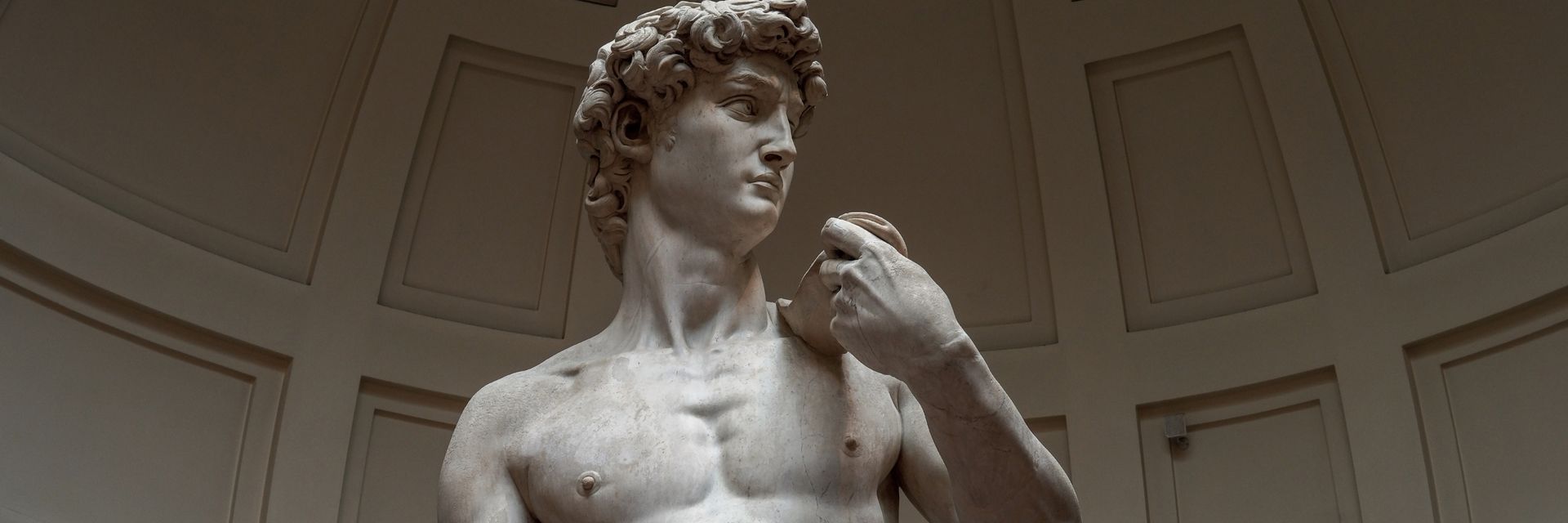

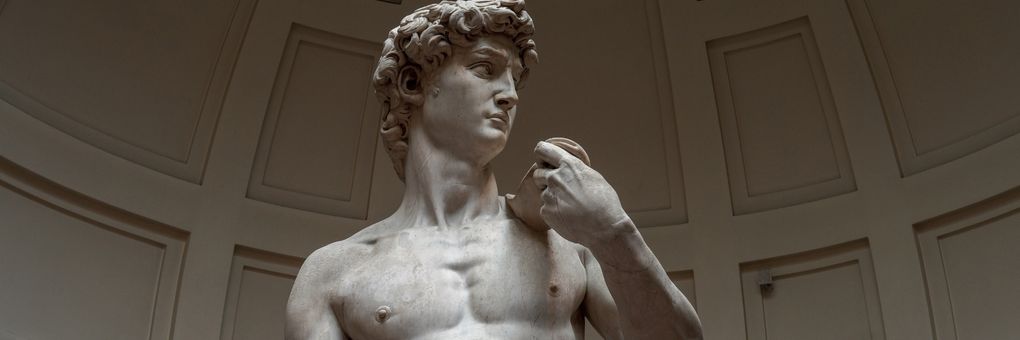

David by Michelangelo (Source: Commonists via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

David: A Symbol of Humanism . . . or Sin?

But not everyone who viewed it was a sophisticated art critic. Changing the perspective at which Michelangelo originally intended it to be viewed brought certain of David’s “assets,” so to speak, much closer to eye level. And though the Renaissance period in which Michelangelo worked was one of revived interest in the arts and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome, antiquity’s ease with and acceptance of the nude in art was not shared by all.

The humanism and neo-Platonism enjoyed in Florence just a generation earlier – when the Medici family ruled Florence and cultivated artists like da Vinci and Botticelli – came to an abrupt end when the Medicis were forced into exile in Rome in 1494, two years after the pater familias, Lorenzo, died. Michelangelo joined his patrons for a time in Rome but returned to Florence in 1501 to accept the David commission, which was a religious project not tied to the Medici program for art patronage.

With the departure of the Medicis, religious conservatives led by Girolamo Savonarola came to power in the city-state. Savonarola replaced the relatively enlightened aesthetic stance of the Medicis with a reactionary religiosity that was welcomed in Florence by many. The Medicis were art patrons, but they were also tyrants who ruled Florence through fear and nepotism, and Florence’s citizens were by and large happy to be rid of them.

But the more accepting social attitudes of the Medici era were replaced by increasingly conservative values, and that directly affected public displays of nudity. Within months after David was installed in the public square, city authorities commissioned a gilded leaf garland for the statue to cover its marble-sculpted genitals. Savonarola’s influence was confirmed.

Michelangelo’s David appears in the public square adorned with a fig leaf, c. 1870s. (Source: National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

The Renaissance and Christianity – An Uneasy Tension

Michelangelo played no role in the decision to conceal David’s nudity. Moreover, he continued to create great art inspired by Classical ideals that included nude figures, as did most of the artists who worked during the Renaissance period and beyond. The great artistic accomplishment that defined his later career comprises the murals he painted for Rome’s Sistine Chapel.

The chapel’s Creation of Adam, for example, portrays a robed deity descending from the skies to bring the touch of divine life – a soul – to the supine nude figure of Adam. And the Last Judgment, in its lower right corner, depicts more than 40 nudes in various stages of torment as they find themselves approaching the terror and torture of Hell.

It’s hard to imagine two moments further separated in time, and in mood. The former depicts the very beginning of humankind’s spiritual life, and the latter represents the final stage of the end of days – the damned’s last moments. The figures are nude in each, but one represents the most innocent of times, pre-sin, and the other conveys the most extreme depth of shame. How can nudity represent both?

That Michelangelo could navigate these polarities of nakedness represents the significant role Christian beliefs played on the Classical influences of the Renaissance. Let’s take a closer look at how Michelangelo and other great minds of that era were influenced by Classical philosophy as well as pre-Reformation Christian beliefs.

One of the key aspects of the Renaissance was humanism, which emphasized the dignity, worth, and potential of human beings. Humanism sought to reconcile the teachings of Christianity with the study of human nature and the world. Renaissance humanists revived the study of Classical languages, literature, and history, believing that by studying the works of ancient thinkers, they could gain wisdom and insight into their own time.

.jpg)

The Creation of Adam (top); The Last Judgment (detail) (bottom). Both are elements of Michelangelo’s painting of the Sistine Chapel (1508–1512). (Source: Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Artists of the Renaissance explored and reinterpreted Christian theology and biblical texts, drawing inspiration from the Church and the works of such early Christian philosophers as Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. They sought to reconcile reason and faith, incorporating Classical philosophy into their understanding of Christian doctrines. This could sometimes be a tightrope walk, particularly when combining the ease of depicting nudes from antiquity with the Catholic Church’s more moralistic view of sex and the “sinful,” post-Edenic body.

As you can see in Michelangelo’s depiction of both Adam and David, nudity was embodied in figures of innocence as well as heroism, representing purity of spirit and deed. But nudity also embodied guilt and shame in the sinful. Michelangelo was successful in depicting both, and he managed to stay in the Church’s graces throughout his lifetime.

But this “golden period” we refer to as the High Renaissance did not last forever. Almost immediately after Michelangelo’s death in 1564, Church officials had the genitals of the many nude figures in the Last Judgment painted over. Moralism, and the powerful impetus of public shame, overtook the appreciation that his art had received during his lifetime.

Nudity and Morality

Pitched battles over nudity in art have continued to this day. Art champions and other progressive thinkers react with horror and opprobrium at attempts to censor nudity and art. On the other side of the cultural chasm, conservatives cry “pornography” at any example of nudity, attacking the freedom – or “license” – of artists to follow their muse, and their aesthetic influences.

A full-sized plaster cast of David was installed in a London museum in 1857. When Queen Victoria first encountered it, she was so shocked, a fig leaf was commissioned to cover the genitalia. The leaf was kept in readiness for future royal visits, when it was hung on the figure using two hooks.

As we have seen, none of this is new. There’s always been a tension between so-called “enlightened” thought and the moralistic concerns of those for whom nudity is always sinful. The artist’s intention doesn’t matter. Whether a piece of art is pornographic depends completely on the viewers’ perceptions, which are colored, of course, by their formative experiences and the cultural context of their lives.

Those individuals who argue that the depiction of David’s nudity, with his exaggerated muscularity and idealized physique, must be seen as sexually provocative are showing their cards. And if their cultural association of the nude body is sexual – and sinful – they will perceive David as morally objectionable as well.

Opponents of this viewpoint argue that viewers are projecting their own sexual desires or interpretations onto the statue. And of course, they’re right. There is no easy resolution, and education in history and aesthetics is unlikely to change that. Michelangelo intended for his David to be seen as pure, heroic, even divinely inspired, but there’s no getting around the fact that some viewers, from Savonarola to the parents of Tallahassee, Florida, cannot see through to that transcendent beauty.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on various topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: David by Michelangelo (Detail) (Source: Commonists via Wikimedia Creative Commons)