Popular culture has romanticized the aviators of World War I. But the evolving state of the equipment and the deadly battles in the skies led many young fliers to early graves.

◊

Less than a decade after the Wright Brothers proved the viability of manned flight on the wind-swept coast of North Carolina, airplanes were pressed into service as weapons of war. The development of lightweight airframes and the engines to power them took off at a frantic pace throughout Europe, Asia, and North America. Specialized weapon development took a bit longer.

The first recorded military use of airplanes (called aeroplanes at the time, after the French aéroplane) was by the Italians in their military action to take control of Libya in 1911. Besides being used in the not-so-new field of aerial reconnaissance – balloons had been flown over battle lines in the late 18th and 19th centuries – the Italians tossed crude bombs on Libyan ground targets. There were similar occurrences in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13. By 1914, Balkan unrest led to the beginning of what would become the Great War, or World War I, when aerial combat of all types came into its own.

Take to the sky with the Royal Flying Corp in its struggle to support the British Army in the trenches below in this dramatic two-part MagellanTV documentary.

France Takes the Lead

As the primary target of German aggression in the West when the war began, France was the number one developer of aircraft and the men who flew the machines. Though other nations allied against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary were pursuing aviation, the French were at the forefront of inventing and using new models of planes and weapons at a level only matched by their chief adversary, Germany. Several French manufacturers, principally Morane-Saulnier and Nieuport, began to rapidly mass-produce airplanes from work begun in the prewar period. Designers, engineers, and mechanics constantly tinkered with their prototypes.

France’s Société provisoire des Aéroplanes Deperdussin was known after its August 1914 reorganization as the more convenient acronym, SPAD.

In the prewar period, French manufacturers licensed their designs to other countries, including Germany. While most common images of World War I planes are of biplanes, with two parallel fixed wings above and below the fuselage, single-wing monoplanes were developed at the same time, with wings above or below the fuselage. Engines were of the radial type or in-line, as in automobile engines. Radial types were lighter and therefore appeared more frequently in early war designs. Among the French-built planes to see early service were the Morane-Saulnier (MS) G and the Nieuport X, both monoplanes, and the Nieuport XB, a biplane. All manufacturers had new letter or number designations for constantly evolving models.

Lafayette Escadrille flying ace Bert Hall (left) with a Nieuport 11 – “Baby Nieuport” – 1918 (Source: En l’Air!, 1918, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lafayette Escadrille flying ace Bert Hall (left) with a Nieuport 11 – “Baby Nieuport” – 1918 (Source: En l’Air!, 1918, via Wikimedia Commons)

Great Britain also had a history of airplane development and was home to aviation visionary Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson, first commander of the Royal Flying Corps. British manufacturers, such as the pioneering firm Royal Aircraft Factory, as well as Vickers and Sopwith, produced monoplanes and biplanes. A popular design for early British planes was the “pusher” model of biplanes, with the engine mounted on the rear of the wing assembly. The Bristol Scout C was a compact early-war monoplane. The design was licensed to several other countries. The Scout and many other airplanes used in 1914–15 were modified or became obsolete as stronger engines and new designs emerged.

Other belligerents mainly relied on the designs and factories of the big three – France, Germany, and Great Britain – for their airplanes. Italy, Romania, Japan, and Canada had one or more homegrown aircraft models, with Italy leading the way. The United States accelerated its aircraft design and manufacturing output exponentially once America entered the war. More than 40 different models were produced, though only the Curtiss flying boats were used in Europe. Russia had its own aircraft industry and employed a designer whose vision and innovation would span over five decades – Igor Sikorsky.

One of the largest aircraft in the skies was the mammoth Il’ya Muromets, a four-engine biplane. Used for reconnaissance, it was equipped with its own defense systems and was a forerunner of the concept used for World War II long-range bombers.

Germany began the war with a number of its own aircraft designs in addition to those models licensed from France and Great Britain. The Taube was an Austro-Hungarian monoplane design and one of the first models used in military service, including by the Italians in Libya. It was the first of many airframes built by Albatros Flugzeugwerke of Berlin.

German Albatros CV 1917 military biplane, pictured with the pilot observer/gunner and ground crew (Source: Library of Congress)

German Albatros CV 1917 military biplane, pictured with the pilot observer/gunner and ground crew (Source: Library of Congress)

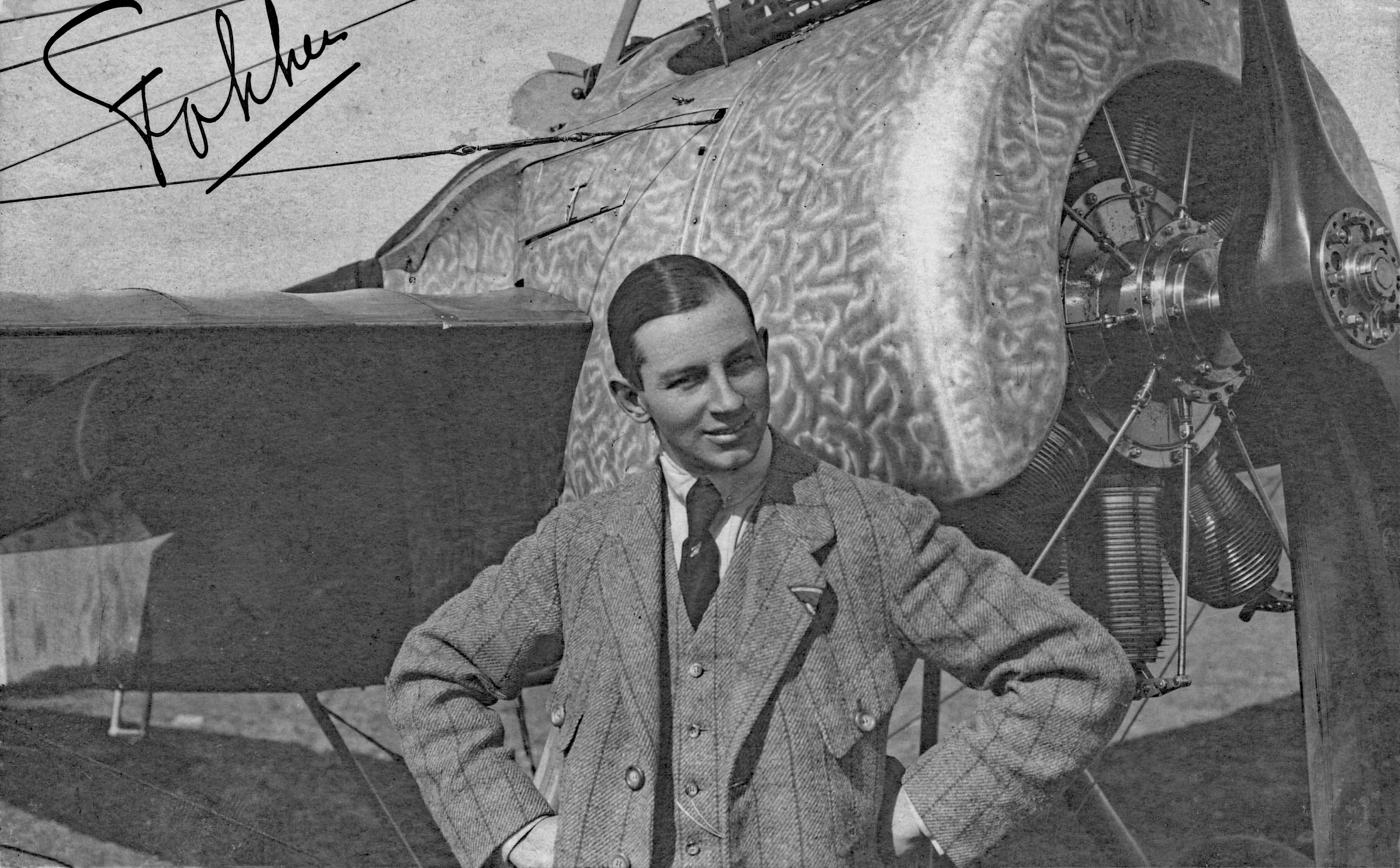

Though the Taube became obsolete early in World War I, Albatros went on to build more than 10,300 aircraft with design modifications spawning over 40 models. These included everything from two-seat observation planes to large bombers. Another aviation pioneer was the Dutch designer Anthony Fokker, who was retained by the German High Command to build planes and equip them with another invention of his that revolutionized aerial armament.

Necessity Is the Mother of the Aerial Machine Gun

From the beginning of the war, the temptation to shoot down enemy pilots existed, despite a forward-looking 1911 treaty signed in Madrid to prohibit air combat. Even though the initial use of airplanes, like the balloons before them, was for battlefield observation, artillery spotting, and intelligence, as soon as one pilot saw an enemy plane in the sky, he would pull out his rifle, pistol, or carbine and try to shoot the opposing fliers, engine, or gas tank. Other than one early Russian pilot who decided to use his plane as a ram, to the detriment of his target and himself, most pilots and their observer/cameramen were prepared with sidearms in case they encountered enemy aircraft.

The most logical choice for the purpose of shooting down other planes was one of the war’s most deadly weapons, the machine gun. By the onset of the Great War, the machine gun had achieved a level of mechanical sophistication to become an automatic weapon. For two-seat aircraft, those used for observation, this was an ideal weapon. The spotter or observer could put down his camera and man a Vickers, Hotchkiss, or other machine gun mounted next to the fuselage cockpit. Pusher aircraft could mount forward facing machine guns the pilot could control. But since most pilots wanted to attack their targets from the rear, a new concept, and a new way of fighting in the air, emerged.

Anthony Fokker in front of his M.5K-MG airplane, a popular German fighter, 1915 (Credit: Unknown German photographer, via Wikimedia Commons)

Anthony Fokker in front of his M.5K-MG airplane, a popular German fighter, 1915 (Credit: Unknown German photographer, via Wikimedia Commons)

How to fire a machine gun without shredding one’s propeller was a challenge solved in the first year of the war. A French pilot, Roland Garros, improved an idea by Saulnier to attach metal plates to the propeller blades where they would cross the path of the machine gun bullets, deflecting them from the fragile wooden prop. Another French design altered the wing design to accommodate the observer-turned-gunner to fire over the top biplane wing.

But the best and most far-reaching solution was developed by Fokker, who mounted a machine gun directly in front of the pilot and used a series of cams to interrupt the machine gun fire when the propeller blades passed through the paths of the bullets. Fokker mounted a 7.92 mm Parabellum machine gun in his M.5K monoplane, which also featured a frame of steel tubing rather than cloth over wood. The Eindecker single-seat scout plane, as the M.5K was called, became the new hot weapon of 1915.

Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines

The Eindecker and other single-seat scout planes began an entirely new objective for World War I aviation. Airmen would go aloft for the purpose of shooting down opposing aircraft. France organized a series of Escadrilles (squadrons) that were formed for aerial combat missions. As they sought out German reconnaissance aircraft to destroy, the Germans countered with planes from its Jasta combat squadrons. These planes were battling each other as fighters – air-to-air combat between pilots known as dogfighting. Not only were the weapons new – fixed machine guns that were fired through the propeller blades or located within the pilot’s reach elsewhere – the flying tactics were different. Reconnaissance pilots maintained level flight unless evading enemy fighters. In dogfights, rolls, loops, and other attack and evasive maneuvers borrowed from stunt flying were a necessity.

Pilots and observer/gunners were young men with pitifully short lifespans. If not killed by gunfire in the air, they often perished as their planes were shot down. The lucky ones either crash-landed in friendly territory and were rescued or came down in enemy areas and became prisoners of war. Those pilots who, through skill and luck, survived to have five confirmed “kills” became “aces” and were the heroes of their countrymen and women.

The Legends Live On

With thousands of aircraft produced, and lost, the material losses during the First World War were staggering. But the deaths in aerial combat were infinitely fewer than those occurring in the land battles across Europe. The impact of air operations started a permanent change in how warfare would be conducted in the future. Brigadier General Billy Mitchell wrote at the end of the war on how air power would change offensive and defensive strategies forever. World War I air power had assumed the role of the cavalry in reconnaissance, aided the role of artillery in tactical bombing, and created a whole new type of warfare in plane-to-plane dogfighting. These roles were tactical in nature, though the idea of strategic bombing was initiated as well, the use of German zeppelins to bomb English cities being the prime example.

Not all World War I flying imagery is of death and destruction. The most famous ace of the war, Germany’s Baron Manfred von Richthofen, who, with 80 kills to his credit, is considered the war’s top ace, remains exemplary both in historical fact and popular entertainment. Richthofen’s disdain for camouflage led to him painting his famous biplane (and later triplane) completely red. His squadron followed suit to protect their leader from being singled out in combat. Other World War I planes were colorful as well – with large bright insignias and paint in national colors along with decorative and meaningful designs and words on the fuselages, the original nose art. Others had colorful names, like the Sopwith “Camel,” named for the hump in the middle created by the housing for its twin Vickers machine guns.

Every country in the war had its heroes. For the United States, Eddie Rickenbacker and Doug Campbell were well-known American aces. But beyond all the glamour and dash of the pilots and planes and dogfights that have been chronicled in the century-plus since the “war to end all wars” ended, it is important to note that the First World War did not achieve that end. Instead it caused an unprecedented loss of life, material, and treasure, followed by a fragile brokered peace that led directly to an even costlier war with greater and more destructive air force operations.

Ω

Jay Wertz is an award-winning author, publisher, and filmmaker. He has written seven books, including four volumes in the War Stories: World War II Firsthand™ series. Other books include The Native American Experience; The Civil War Experience 1861–1865; and Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, co-authored with Edwin C. Bearss. He is the editor and a primary contributor to D-Day 75th Anniversary – A Millennials Guide and other works for Monroe Publications. He has been a columnist and online contributor for Civil War Times Illustrated, America’s Civil War, Aviation History, Armchair General, and America in WWII magazines. He is also the producer-director-writer of the documentary series Smithsonian’s Great Battles of the Civil War for The Learning Channel and Time-Life Video.

Title Image: A Bristol F.2B fighter of No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps in Palestine, February 1918 (Source: Australian War Memorial, via Wikimedia Commons)