In what ways has Spanish culture impacted the daily lives of today’s Filipinos?

◊

Like many countries around the world, the Philippines has experienced a long history of European colonization. When Magellan and the Spanish finally reached the archipelago, they brought many culinary, artistic, and religious influences with them.

Many changes were unwelcome, and Filipino resistance would inform later art and culture. But other Spanish influences, including the Catholic religion, were absorbed into Filipino daily life and the independent country that would eventually emerge.

Whether you’re curious about Spain's influence on Filipino cuisine or how Spanish mingled with Indigenous languages to create a new language altogether, let's take a look at how the colonization of the islands significantly informed the future of the Philippines.

The Philippines are but one group of many islands in the Pacific Ocean. Learn about the culture and history of some of them in this engaging MagellanTV documentary.

Filipino Dishes Survived Spanish Colonial Occupation

Many dishes that marry Spanish and Filipino cultures are well known in the country. They include such meals as Arroz Valenciana, a Filipino take on paella that includes hard-boiled eggs and chorizo, and Afritada, a tomato-based chicken stew that was among the first Filipino dishes to require pan-frying, a technique that Spaniards introduced to the archipelago.

Other popular dishes are based on recipes that have been around since long before Spaniards arrived in 1521. Two of these follow below.

Adobo

If you’re familiar with Filipino food, you've likely had the pleasure of eating adobo. The name of this dish comes from “adobar,” the Spanish verb for "to marinate." Though the Philippines has too many delicious culinary treats from which to choose a single national dish, no one can doubt the immense popularity of adobo across all classes of Filipino society.

The cooking process is simple but time-consuming. You begin by searing evenly cut chunks of meat in oil or fat until brown. Then, you braise the meat with vinegar and soy sauce, simmering everything on low heat for several hours until all the collagen and fibers yield to the tender texture everyone loves.

No more than three factors typically trip up a first-time cook: If you swap seafood or poultry for red meat, you must cook for less time to prevent the protein from disintegrating completely. Also, avoid excess heat. If the outside cooks too fast, the meat will toughen. Finally, mind the salt. There’s plenty in the soy sauce, but you can add some to taste near the end of the process.

Interestingly, rather than drawing inspiration from Spanish cooking, Filipino adobo received its name from incoming Spanish occupiers who compared it to adobo back in Spain and their colonies in the Americas. But, because imperial languages were often absorbed by (or imposed upon) native people, the name stuck.

Distinct from the fiery adobo of Spain and the tangy adobo of Mexico, Filipino adobo prizes practicality as well as flavor. In addition to the modicum of kick its spices provide, its vinegar and soy sauce are acidic enough to kill any invading bacteria.

As a simple dish, the Filipino adobo of today is flexible enough to include a variety of meats, textures, spices, and Spanish or Indigenous techniques. Accordingly, restaurants around the world put their own spin on this classic meal.

Sinigang

Another dish whose popularity remains significant at a much less global scale is sinigang, which means “stewed” in Tagalog. Most consider it a soup, but because it’s so thick with chunks of meat and vegetables as to be more like a stew, it almost always serves as a main dish.

Naturally, there’s a lot more to sinigang than meat and vegetables. This delicacy receives most of its signature tang from tamarind, but many of today’s cooks embellish that tartness with mango or guava. The meat’s umami mixes with the tang, offering a flavor combination as iconic as peanut butter and chocolate! As central as tang and umami are to the dish, some also add bananas for extra sweetness or chili flakes for extra kick.

A beautiful bowl of sinigang (Credit: Jay D. Ganaden, via Wikimedia Commons)

A beautiful bowl of sinigang (Credit: Jay D. Ganaden, via Wikimedia Commons)

Distinct from other aspects of Filipino culture, sinigang preceded and has remained largely untouched by colonial influences. Not only has it persisted as one of the most popular comfort foods around which large families gather, but it’s also accessible and easy to make because it requires only local ingredients. Spaniards had neither the interest nor the reason to change it.

Languages of the Philippines

“Filipino” is a language as well as a nationality. It’s an easily teachable and standardized version of Tagalog, which originated on Luzon, the country’s largest and most populous island. This national language has changed from Tagalog to Filipino gradually over the past century, but the two exhibit non-negligible differences. For example, the Tagalog alphabet contains 20 letters, while the Filipino alphabet contains 28 letters to include loanwords from Western languages. Today, the government of the Philippines acknowledges Filipino and English as the official languages of the nation.

Fun fact: If you spent one day on each island in the Philippines, your vacation would last for 21 years!

There are 7,641 islands in the Philippine Archipelago, and 21 languages are spoken across various regions. Most of them are from the Malayo-Polynesian language sub-family, and Cebuano is the most common of these. Only Chavacano, a creole spoken by about 1.2 million people, has a strong Spanish influence. But Filipino is the language you’re most likely to hear across the country – in schools as well as in mass media such as television, radio, and cinema.

Catholic Holidays Adapt to Filipino Culture

On March 16, 1521, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese commander acting on behalf of Spain, reached the shore of Cebu, one of the islands in the center of the Philippine archipelago. He managed to “persuade” the local ruler, Rajah Humabon, and his wife, Queen Humamay, to pledge allegiance to Spain. Later, the rajah and queen were baptized into Catholicism and took the names King Carlos and Queen Juana. At the baptism, they were presented with a wooden statuette that depicted Jesus as a child.

Magellan wasn’t welcomed by all Indigenous people to the islands. Just over a month after he landed on Cebu, he was killed on April 27, 1521, in the Battle of Mactan. Surviving members of the expedition departed, and Spaniards did not return for 44 years.

Whether by acceptance or imposition, Catholicism eventually took root in the Spanish colony. Today, the religion’s advent there is commemorated on the third Sunday of each January by the Feast of Santo Niño, which takes its name from the diminutive statuette Magellan presented. But, rather than celebrating Spanish conquest, the holiday focuses on the arrival of Catholicism.

The Feast of Santo Niño

Like many holidays across all cultures, the Feast of Santo Niño is mostly about family and food. But in addition, Filipinos commemorate the advent of Catholicism in their islands with Jesus statuettes of their own. These curios are as abundant during the Feast of Santo Niño as nutcrackers are on Christmas. Congregants in Filipino churches often parade their Jesus statues about the pews.

The Fluvial Parade re-enacts the arrival of Magellan in Cebu. (Credit: Kliencyril08, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Fluvial Parade re-enacts the arrival of Magellan in Cebu. (Credit: Kliencyril08, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Pahiyas Festival

Another major holiday in the Philippines is the Pahiyas Festival, a celebration similar to Thanksgiving in the U.S. and beyond. Distinct from other harvest celebrations, the Pahiyas Festival takes place on May 15 east of Manila in the city of Lucban and the greater province of Quezon.

For the past few decades, the people of Quezon have celebrated this holiday by decorating their houses with fruits, vegetables, and flowers. In celebration of abundance, neighbors are encouraged to pick produce off each other’s houses. Displays across Quezon are colorful, especially in Lucban, where municipal workers decorate public structures, like bridges and churches, with multi-colored produce. Many also decorate their homes with longganisa sausage, a staple of Filipino meals, which has a strong garlic flavor (thankfully, it isn’t as pungent as it tastes).

Other Pahiyas customs include dressing nicely and gathering with family for a big dinner. Seasonal dishes include pancit habhab, a noodle dish to eat with bare hands from a banana leaf; hardinera, a Filipino take on meatloaf; and espasol, a rice cake one cooks and sweetens with coconut.

Though several Pahiyas traditions are recent, the earliest Pahiyas celebrations in the 1500s and 1600s were dedicated to thanking San Isidro Pahiyas, the patron saint of farmers, for his assistance with the harvest.

A storefront in Lucban during the Pahiyas Festival (Credit: Ralff Nestor Nacor, via Wikimedia Commons)

A storefront in Lucban during the Pahiyas Festival (Credit: Ralff Nestor Nacor, via Wikimedia Commons)

Indigenous Styles Persisted in the Arts

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the 1500s, visual art across the Philippines often depicted animals, nature, and characters from local mythology. This art didn’t begin and end with paintings, as other popular media included textiles and sculptures of different materials. Ancient communities used this art to distinguish themselves from each other and to illustrate their own meaningful connection to nature.

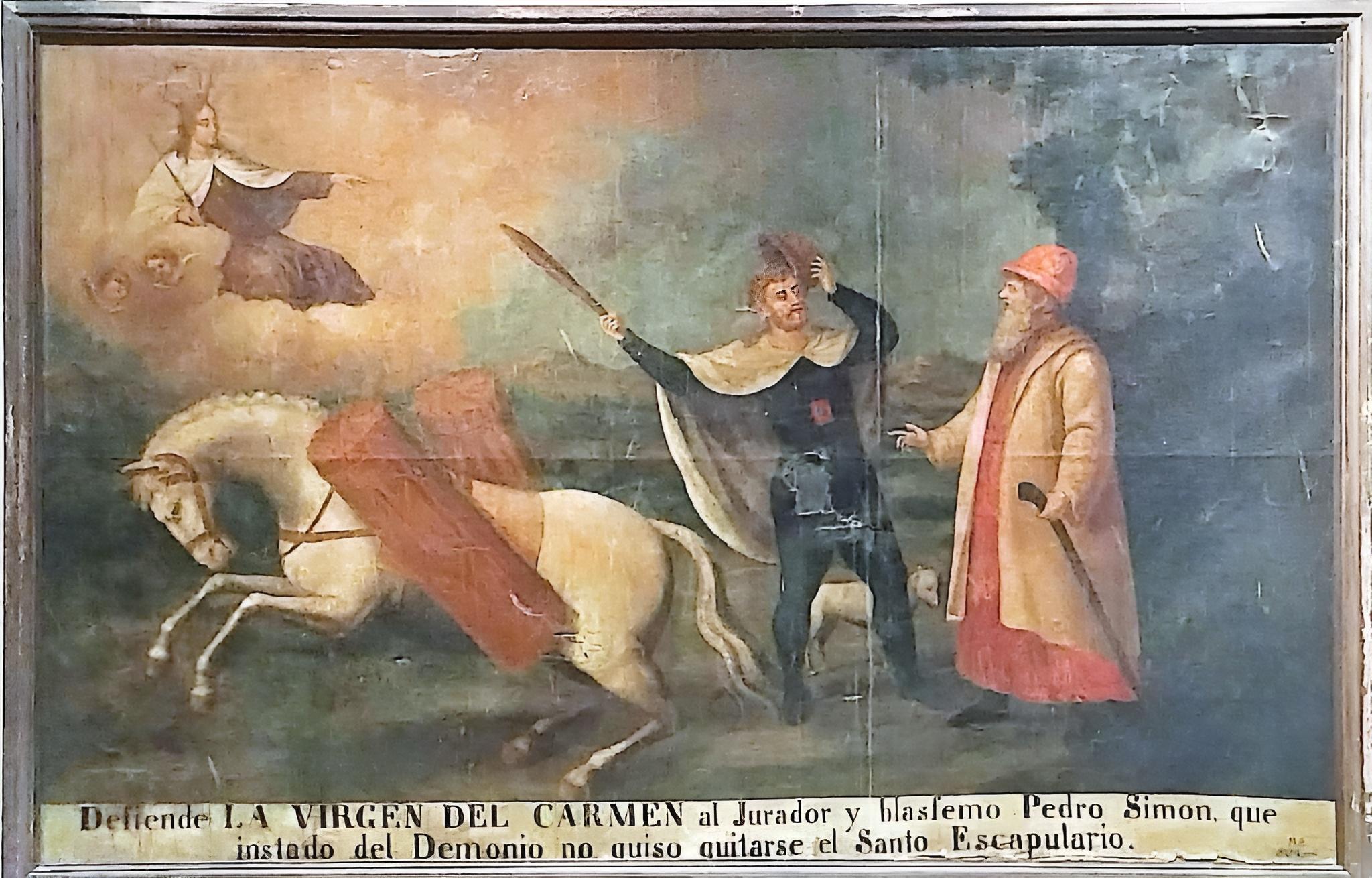

When the Spanish established control – and inevitably labeled native arts as inferior to European styles – colonial authorities enslaved many locals, including Indigenous artists. The Spaniards forced these artists to abandon traditional subjects and techniques in favor of Catholic iconography displayed upon walls of new churches.

Thankfully, Indigenous artists managed to preserve their traditions by fusing their native style with the new Catholic art the Spanish forced them to create. Thus, hints of Indigenous tradition persisted throughout colonial paintings, sculptures, and even architecture. Both local and European techniques informed projects as large as churches and government buildings.

La Virgen del Carmen by Mariano Asuncion, 19th century (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

La Virgen del Carmen by Mariano Asuncion, 19th century (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The influence of almost 400 years of Spanish colonial rule lingers in the Philippines, but it’s not as dominant and pervasive as one might imagine. In cuisine, language, the arts, holidays, and culture generally, the enduring markers of Indigenous peoples have not only survived but thrived.

Like many other countries, the Philippines faces deeply serious challenges caused by climate change, political polarization, and interference by foreign powers, among other sources. But enjoying a tasty plate of Filipino adobo or sinigang with family and friends might help provide a brief respite from those problems, reminding us that the roots of communities reach deep for nourishment.

Ω

Ben Sernau is a prolific marketing professional whose articulate content has boosted SEO for businesses across the nation. Between a growing YouTube channel and work for clients, Ben keeps his hands full with a variety of topics. Ben is also an avid gamer, enjoying any topic tangentially related to games. He writes from Mamaroneck, New York.

Title Image: A street in Lucban during the San Pahiyas Festival (Credit: Patrickroque01, via Wikimedia Commons)

.jpg)

.jpg)